Lecture Notes 21: Mapping Reducibility

Outline

This class we’ll discuss:

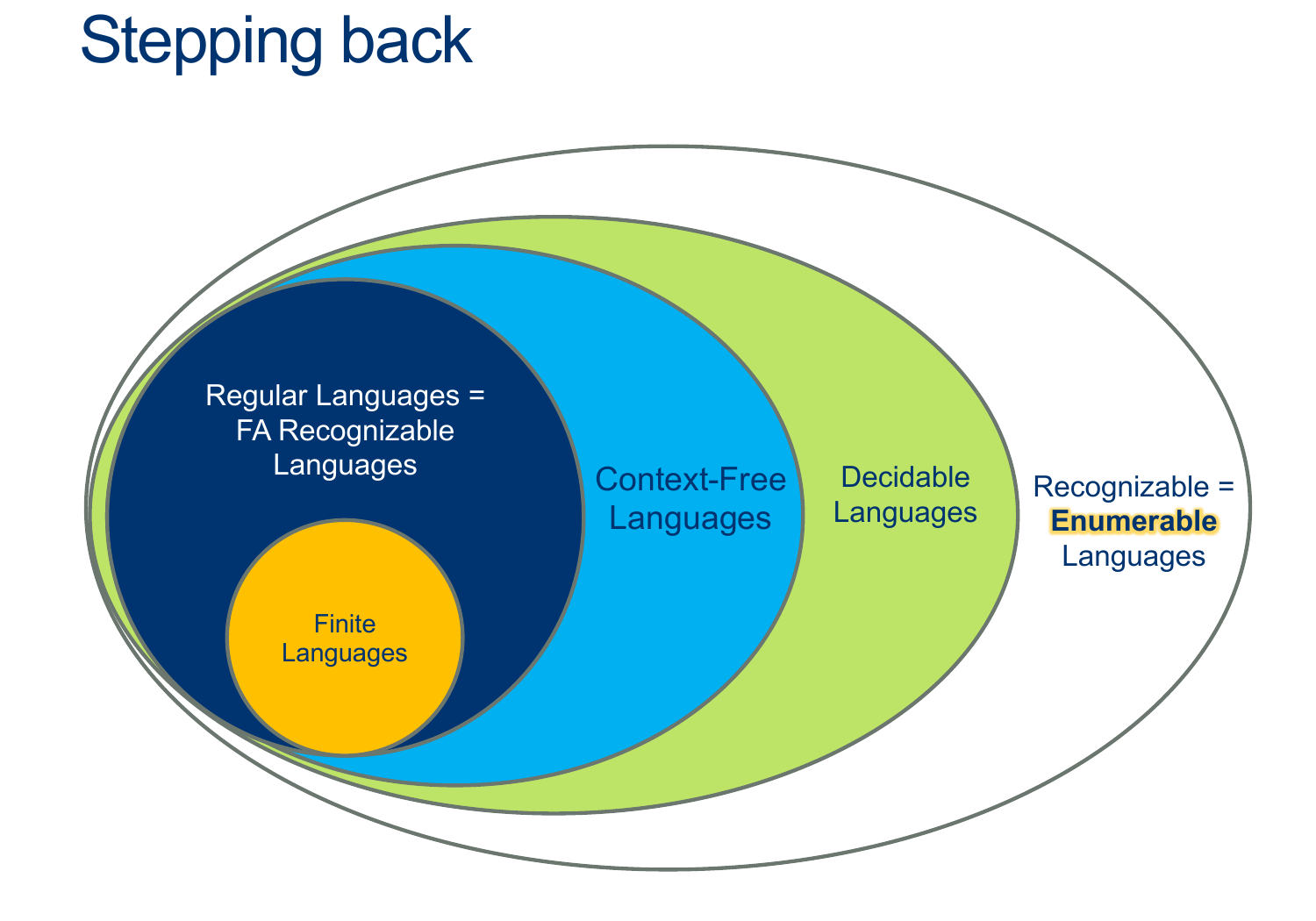

- Recap: Enumeration and Recognizers

- Mapping reducibility

A Slideshow:

GUIDED NOTES (Optional)

Mapping Reducibility

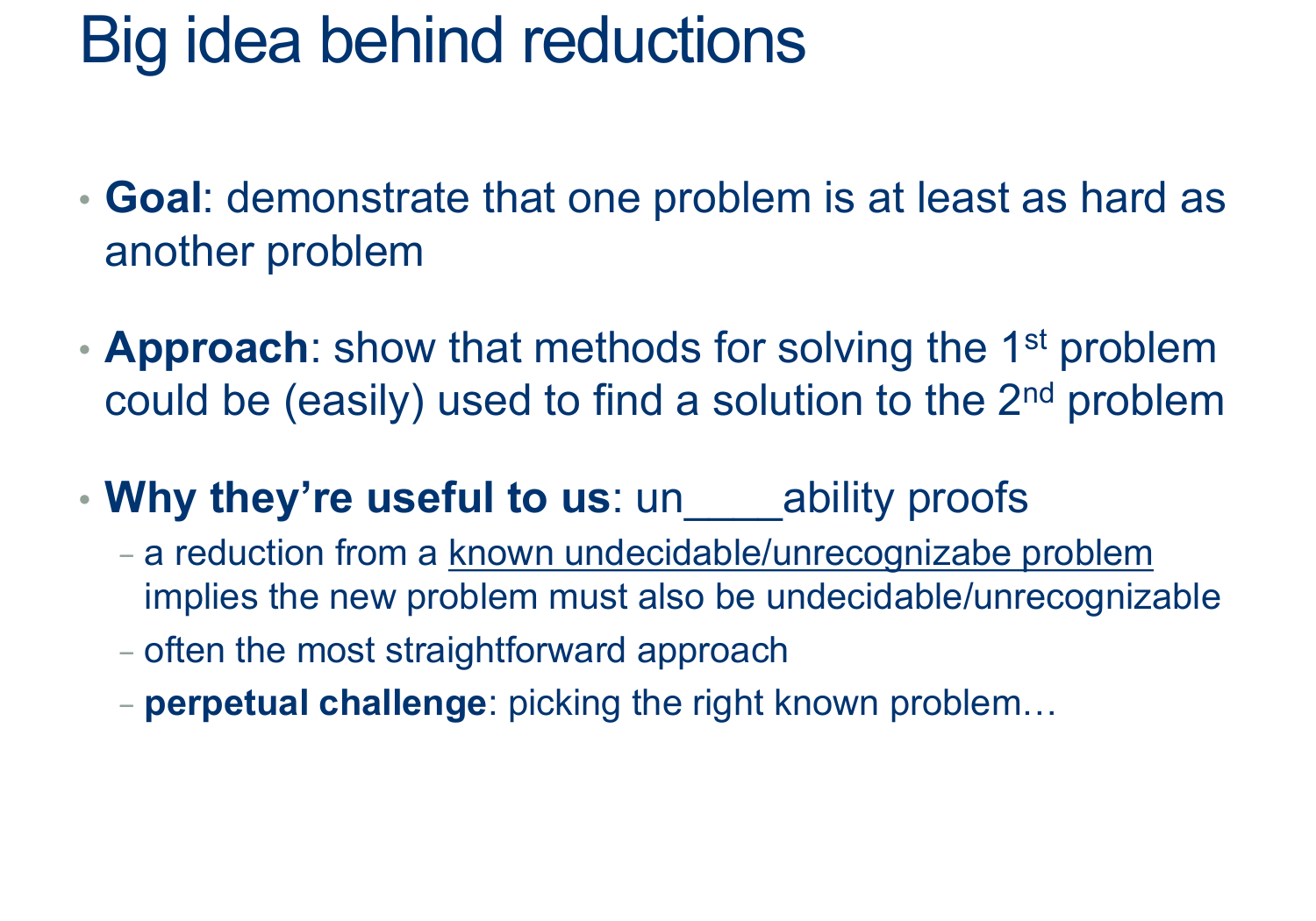

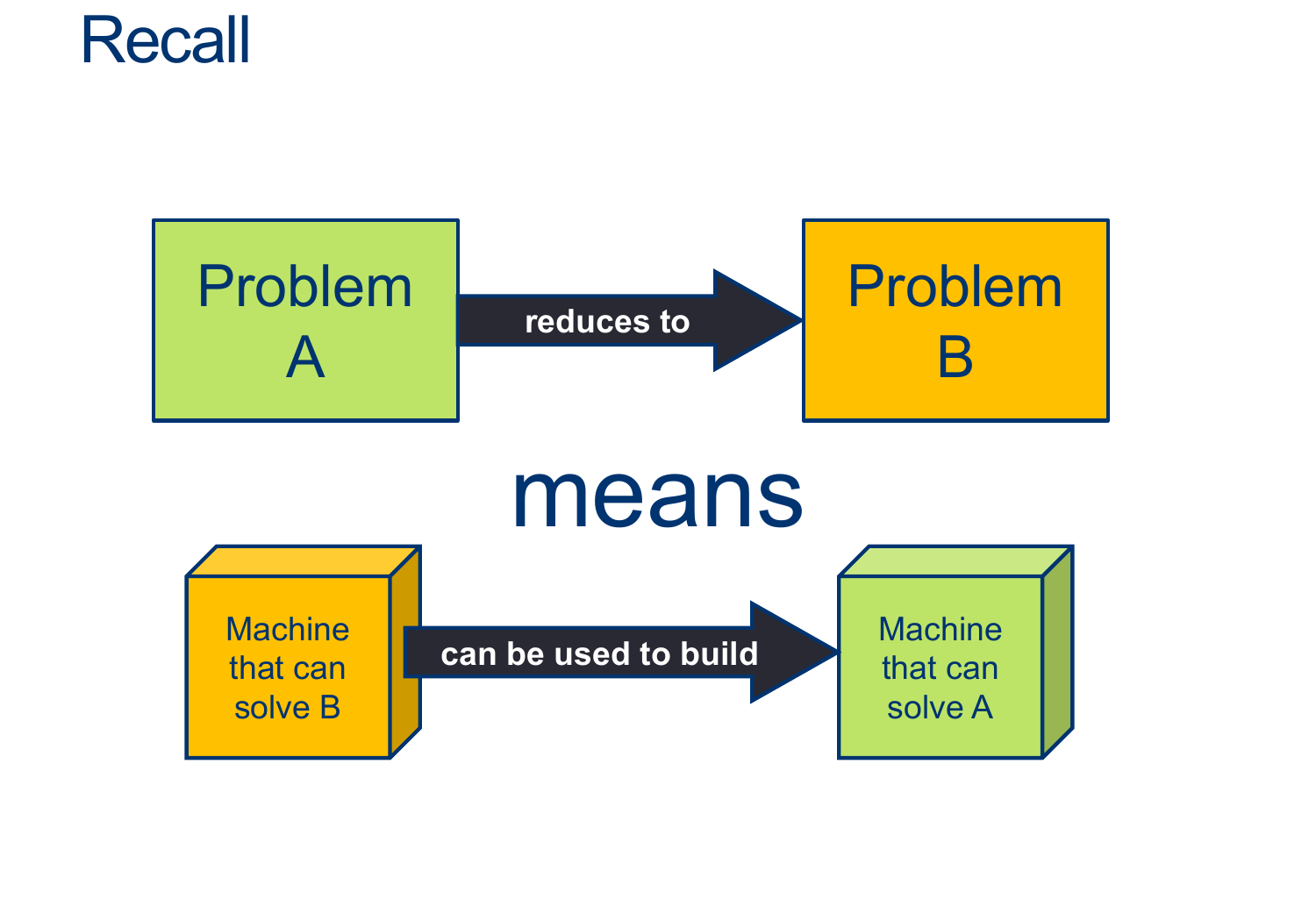

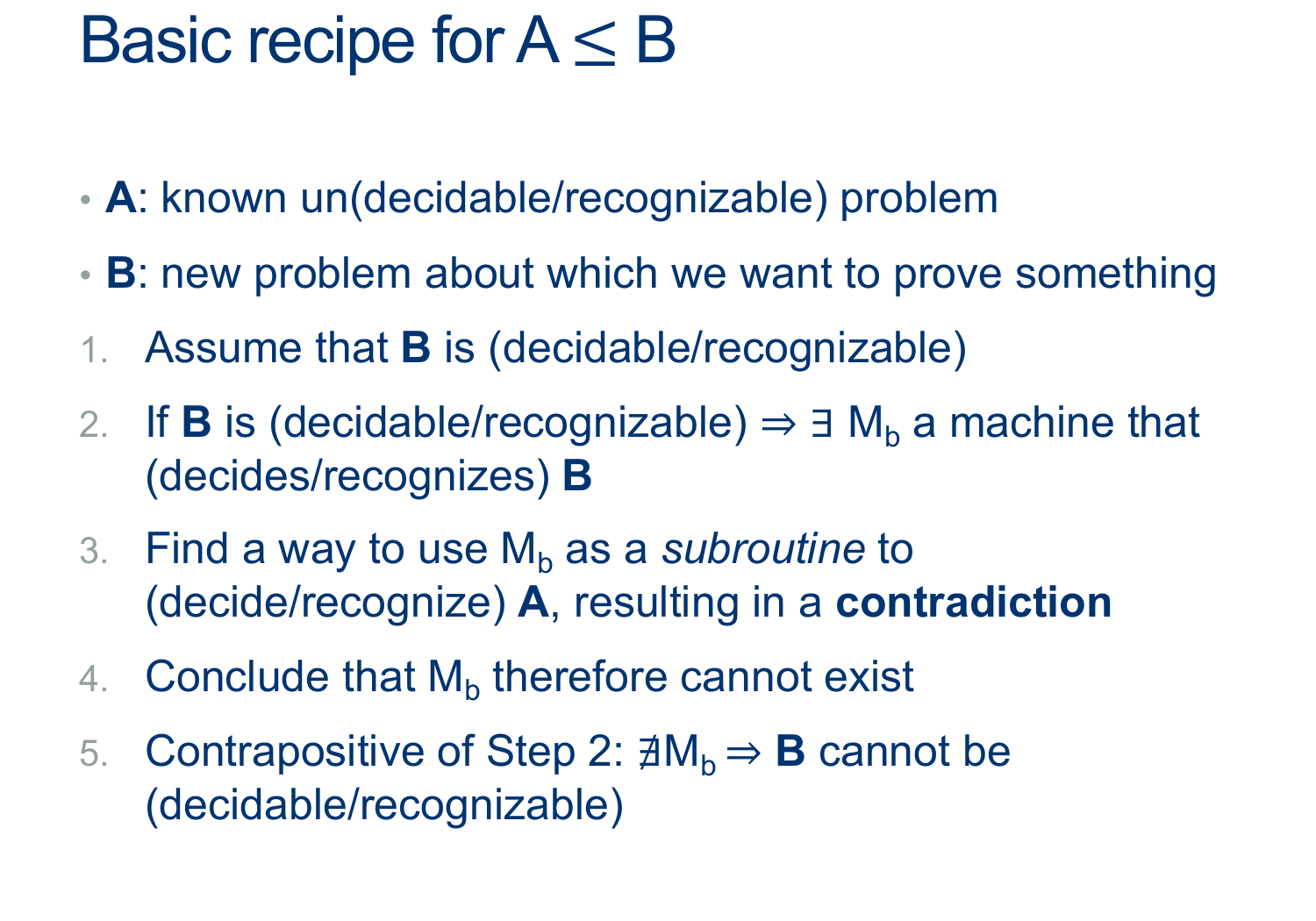

Recap: Reductions

Activity 1 [2 minutes] How would you do this reduction?:

Activity 2 [2 minutes] How would you do this reduction?: (Wait; then Click)

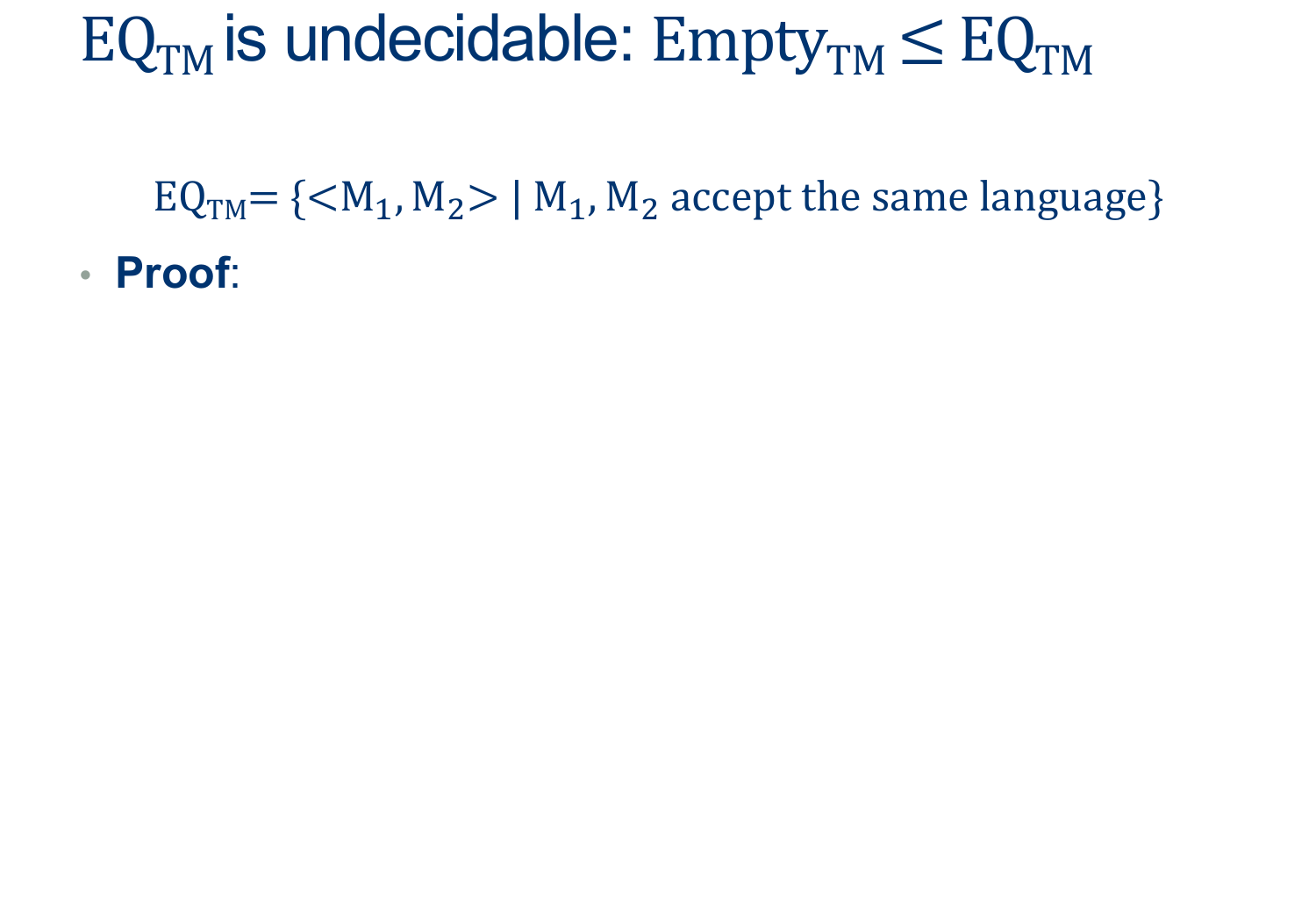

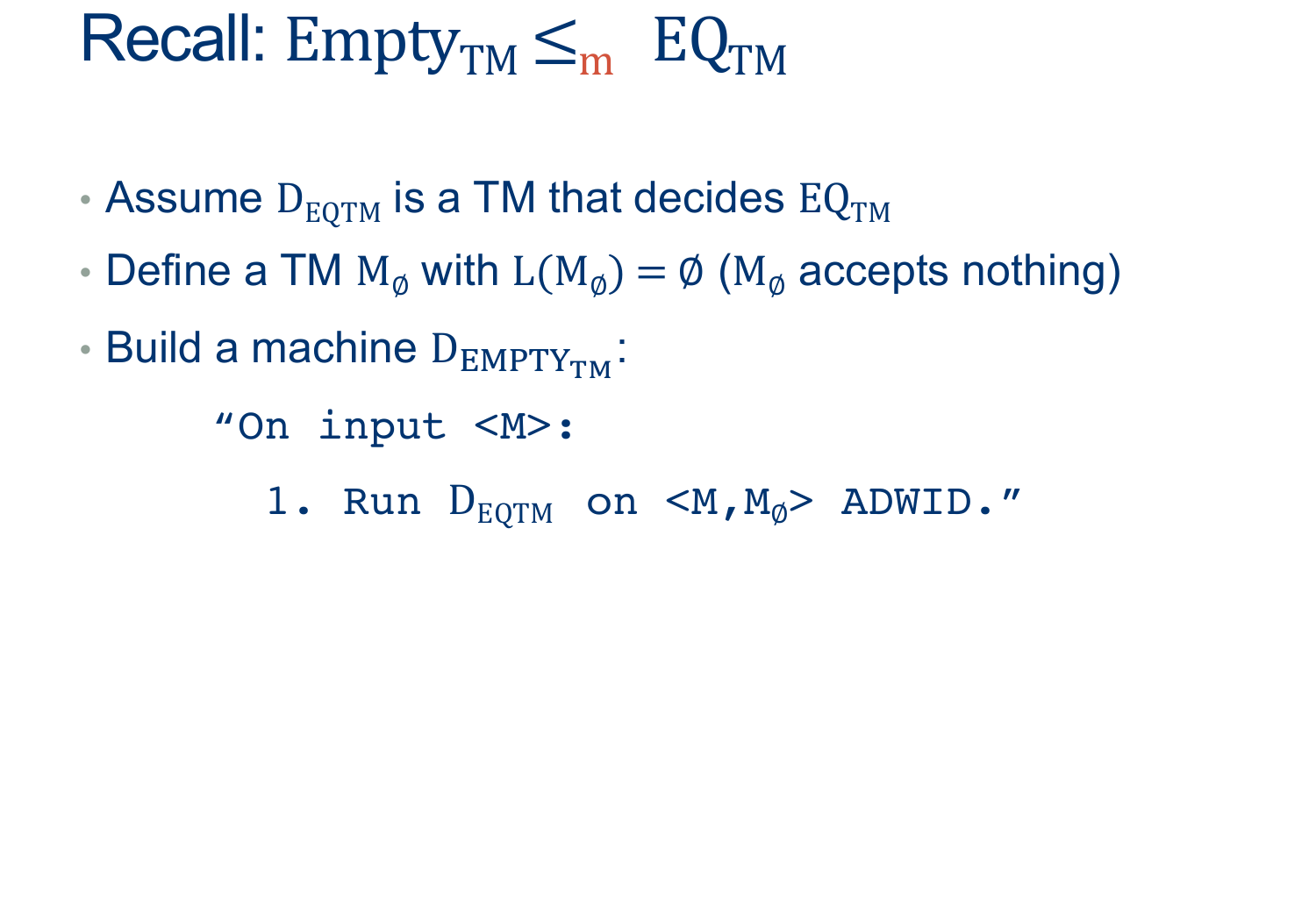

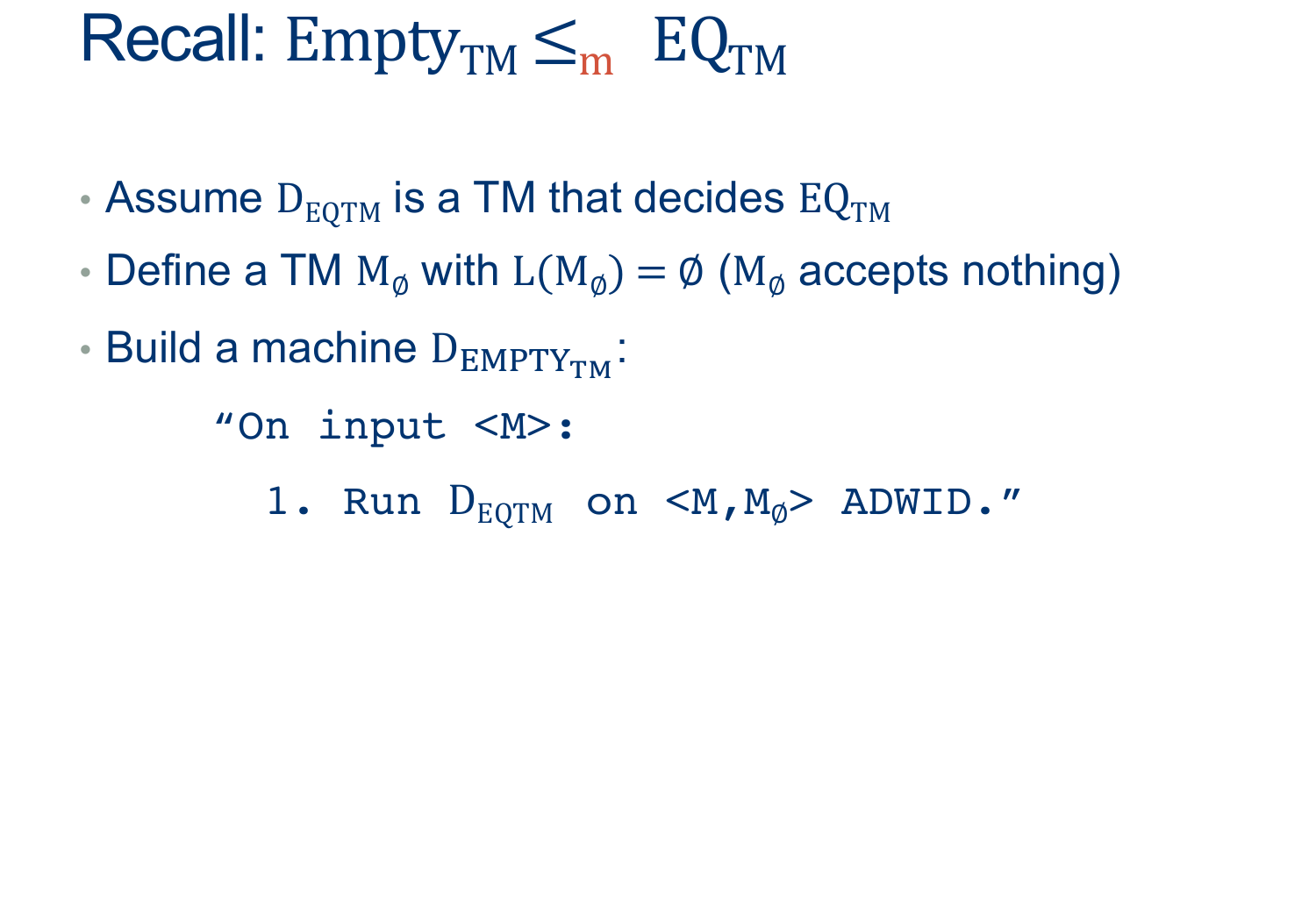

Assume EQTM is decidable, and so there exists some $D_{EQTM}$ that decides, for any input $< M_1, M_2>$, whether $M_1$ Accepts the same language as $M_2$.

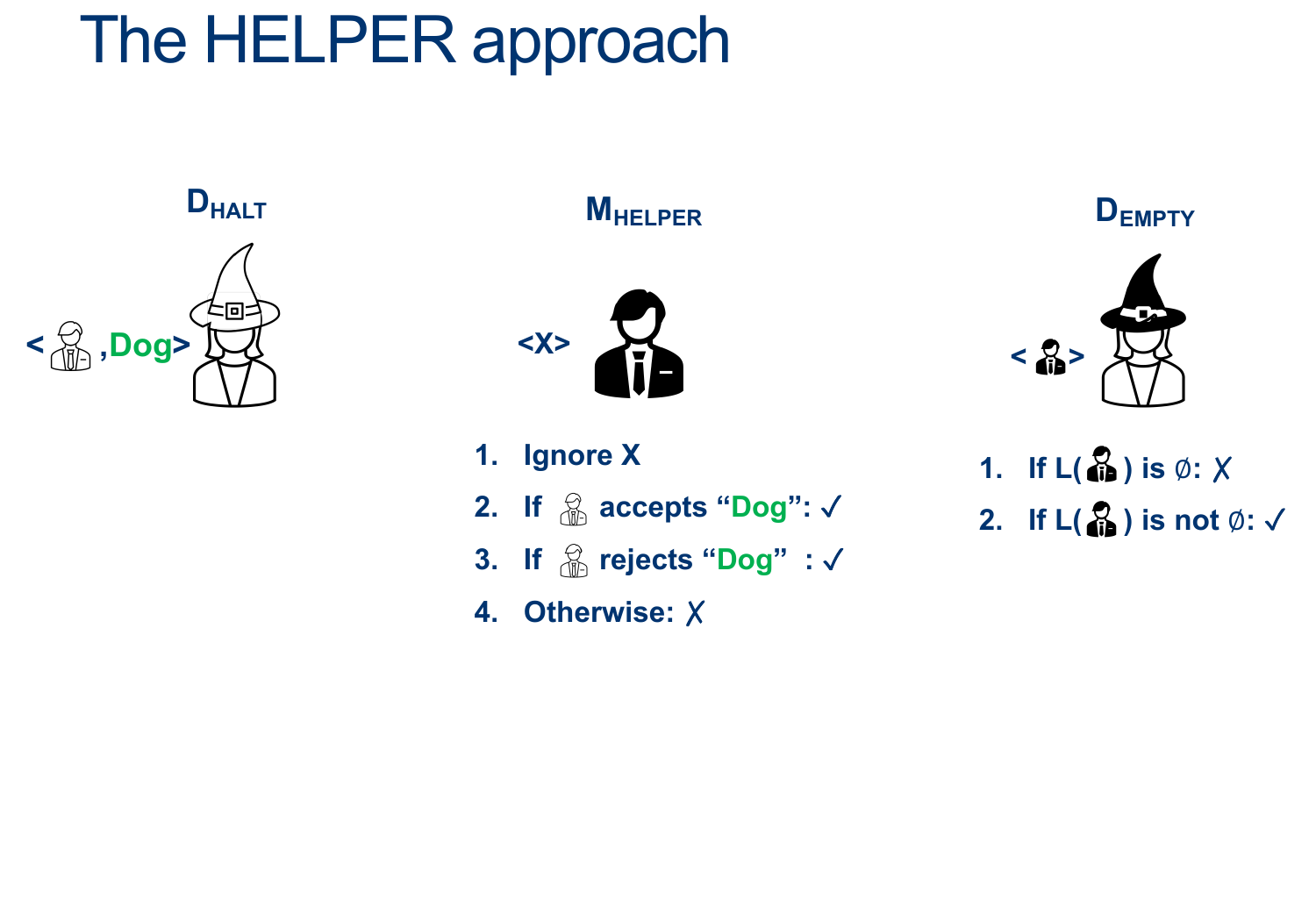

We’ll design the Machine $D_{EmptyTM} $ as follows:

\[\begin{align*} &D_{EmptyTM}:\\ & \text{ On input $ < M > $ }:\\ & \text{ Create (but don't run) $HELPER_{\emptyset}$ such that}\\ & \quad \text{ On input $ < X > $ }:\\ & \quad \quad \text{ Ignore $ < X > $ }\\ & \quad \quad \text{ Reject}\\ & \text{ Now Run $D_{EQTM}$ on input $ < M, HELPER_{\emptyset} $ ADWID}\\ & \text{ If $D_{EQTM}$ accepts, it is only because M accepts no words so our machine ACCEPTS}\\ & \text{ If $D_{EQTM}$ rejects, , it is only because M accepts some w so our machine REJECTS}\\ \end{align*}\]

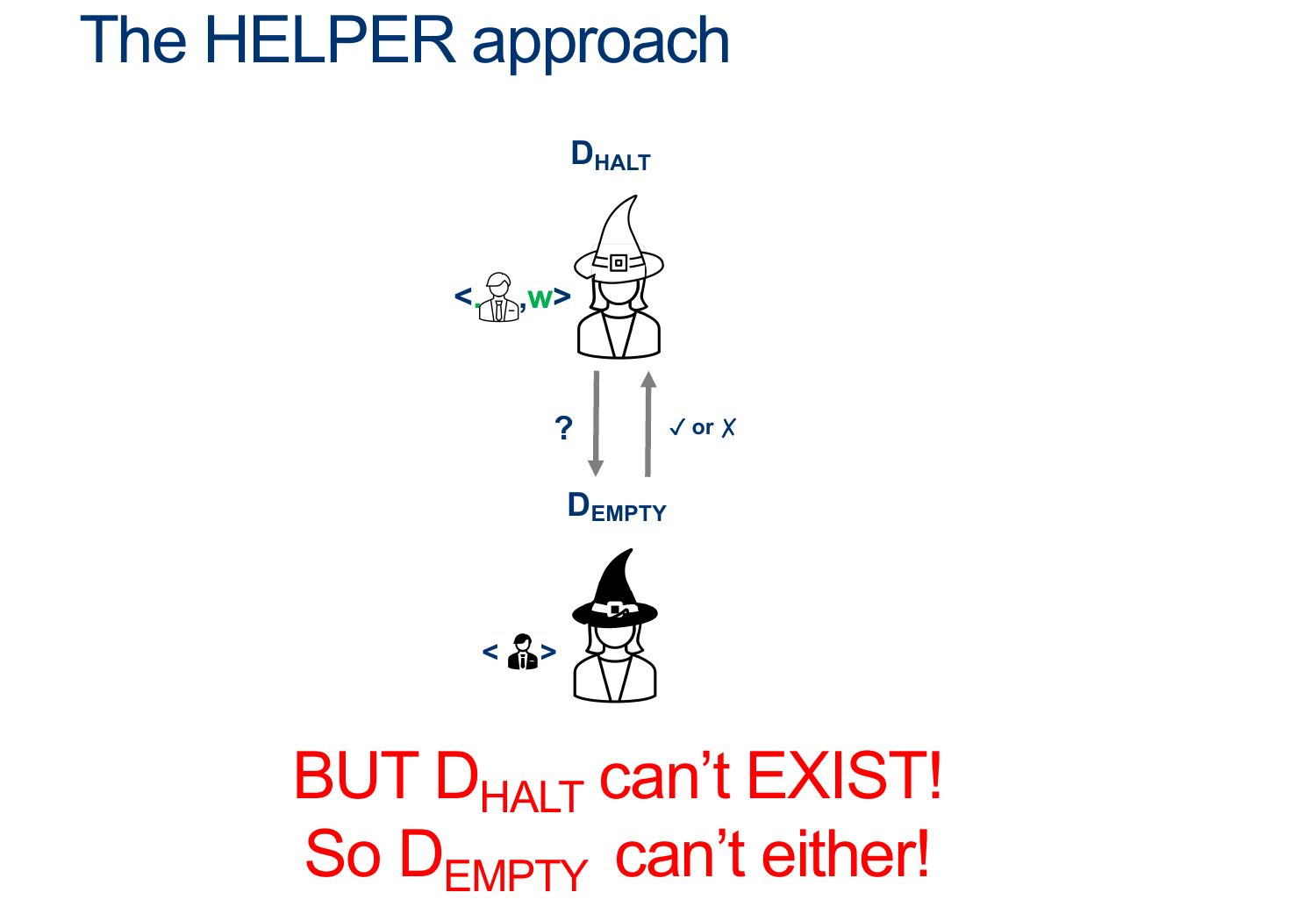

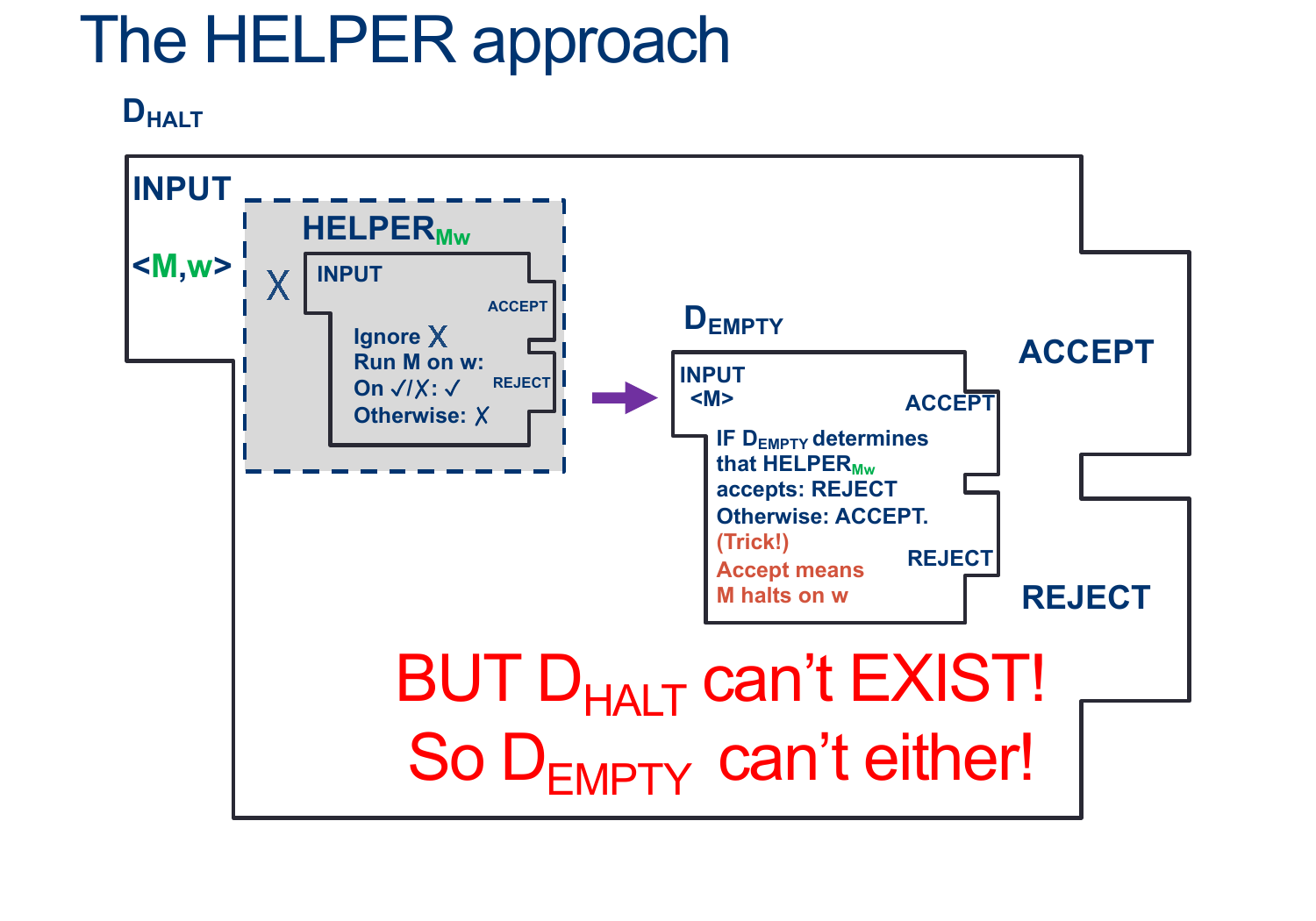

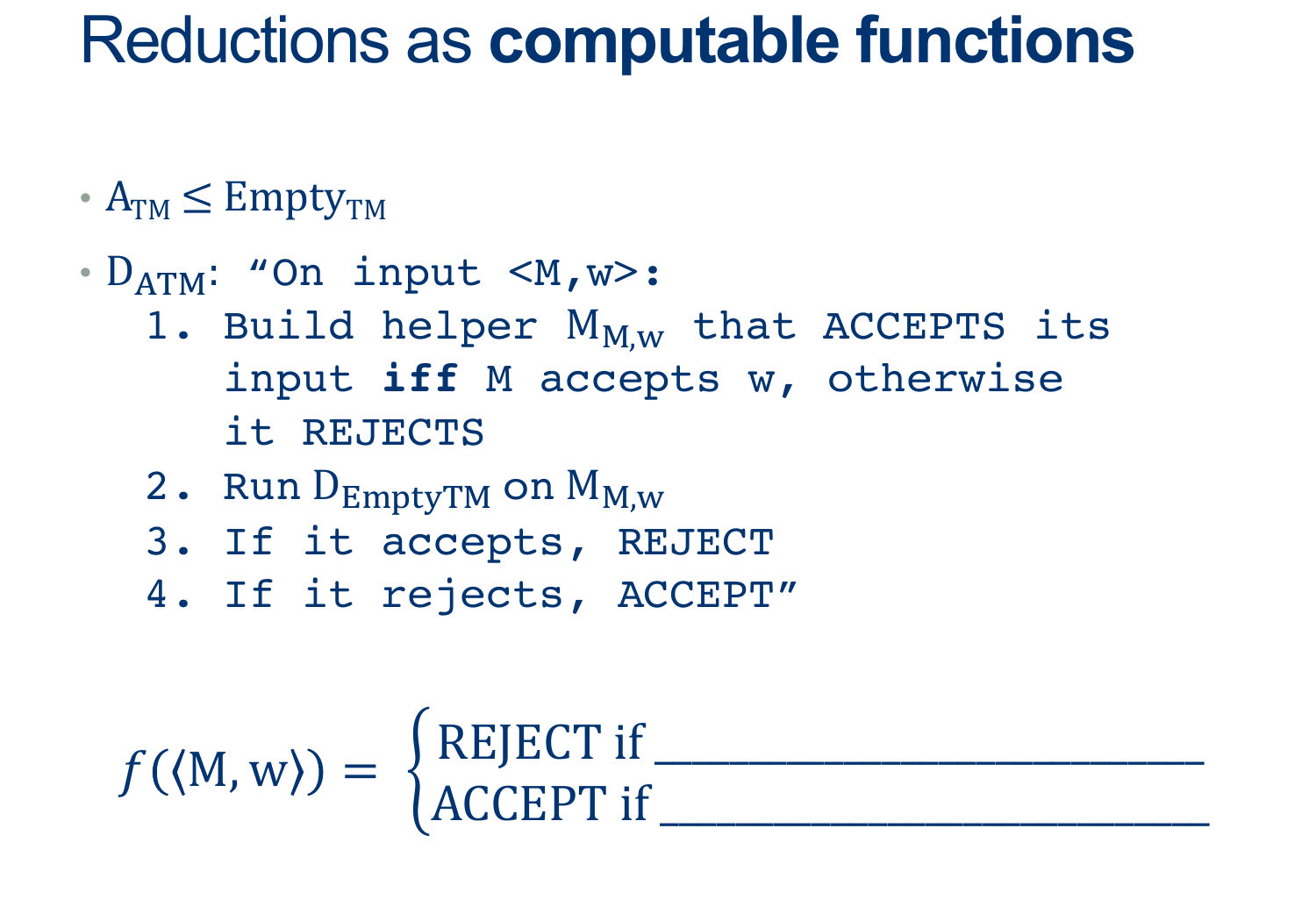

Activity 3 [2 minutes] How would you do this reduction?: (Wait; then Click)

- Reject if: $D_{EMPTY}$ accepts $M_{M,w}$

- Accept if: $D_{EMPTY}$ rejects $M_{M,w}$

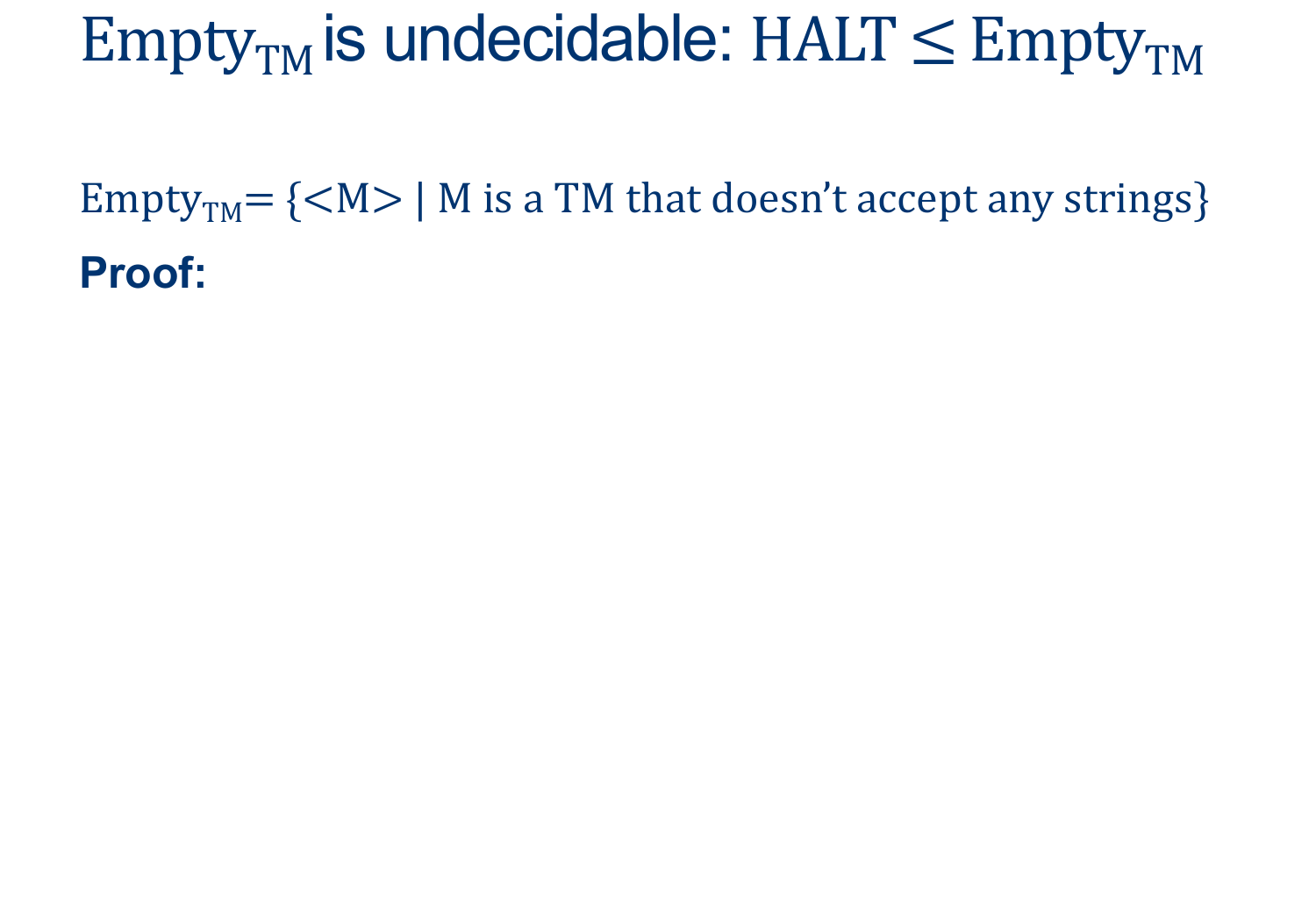

The Emptiness Problem

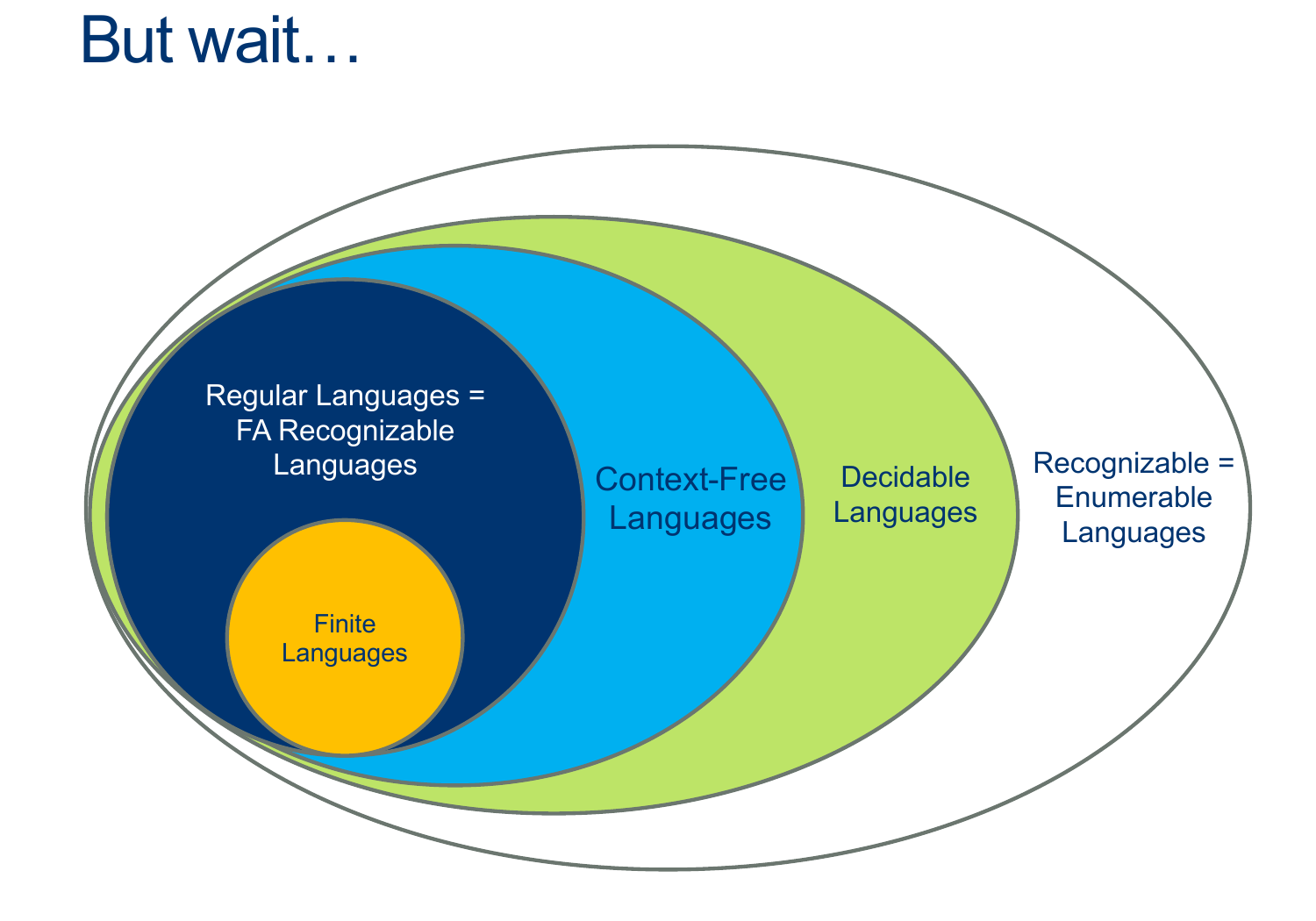

- Theorem: $\overline{EMPTY-TM}$ is recognizable

- Theorem: $EMPTY-TM$ is undecidable

- Corollary: $EMPTY-TM$is unrecognizable

- Proof: If $\overline{EMPTY-TM}$ and $EMPTY-TM$ recognizable,

- that would imply $EMPTY-TM$ is decidable

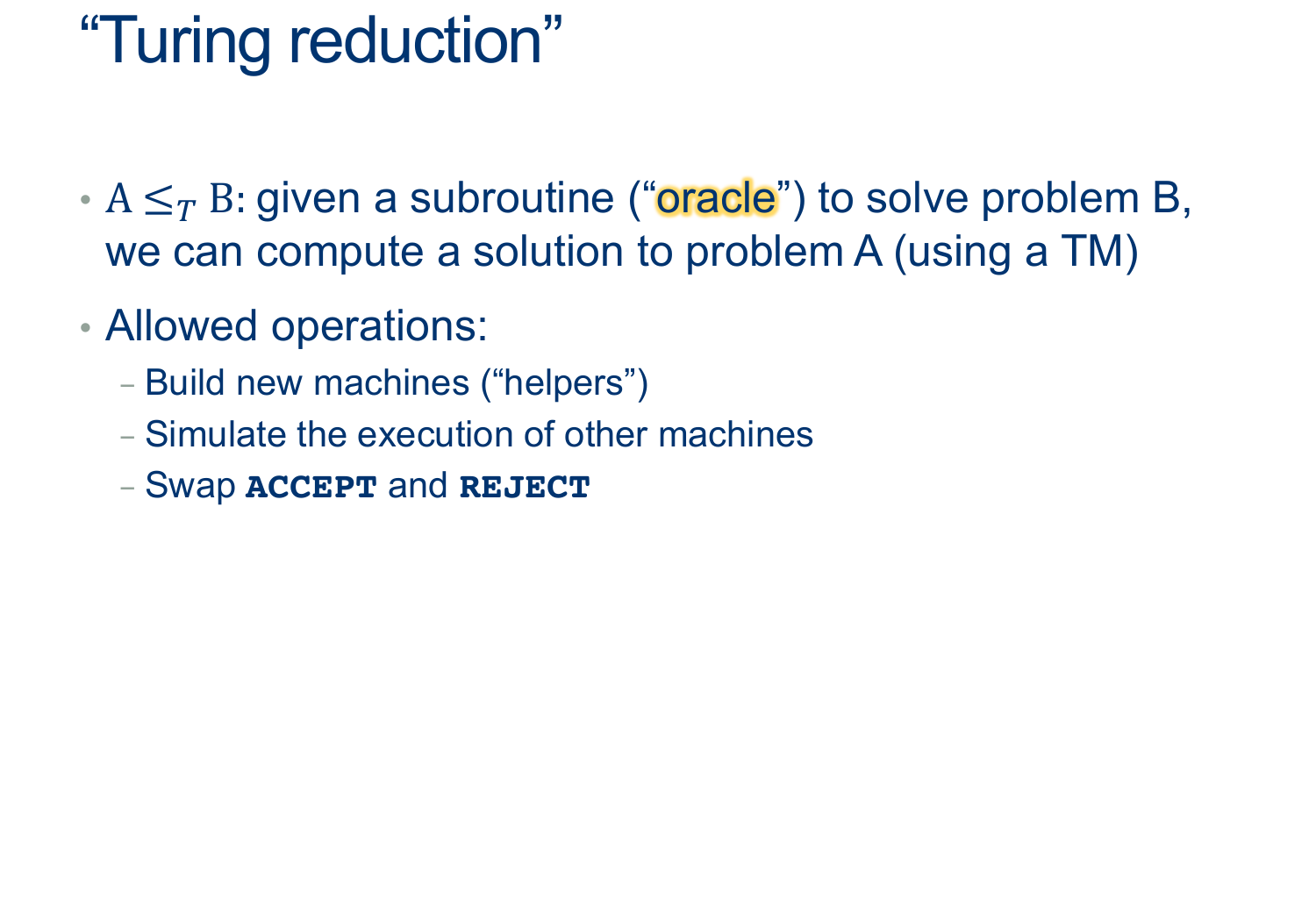

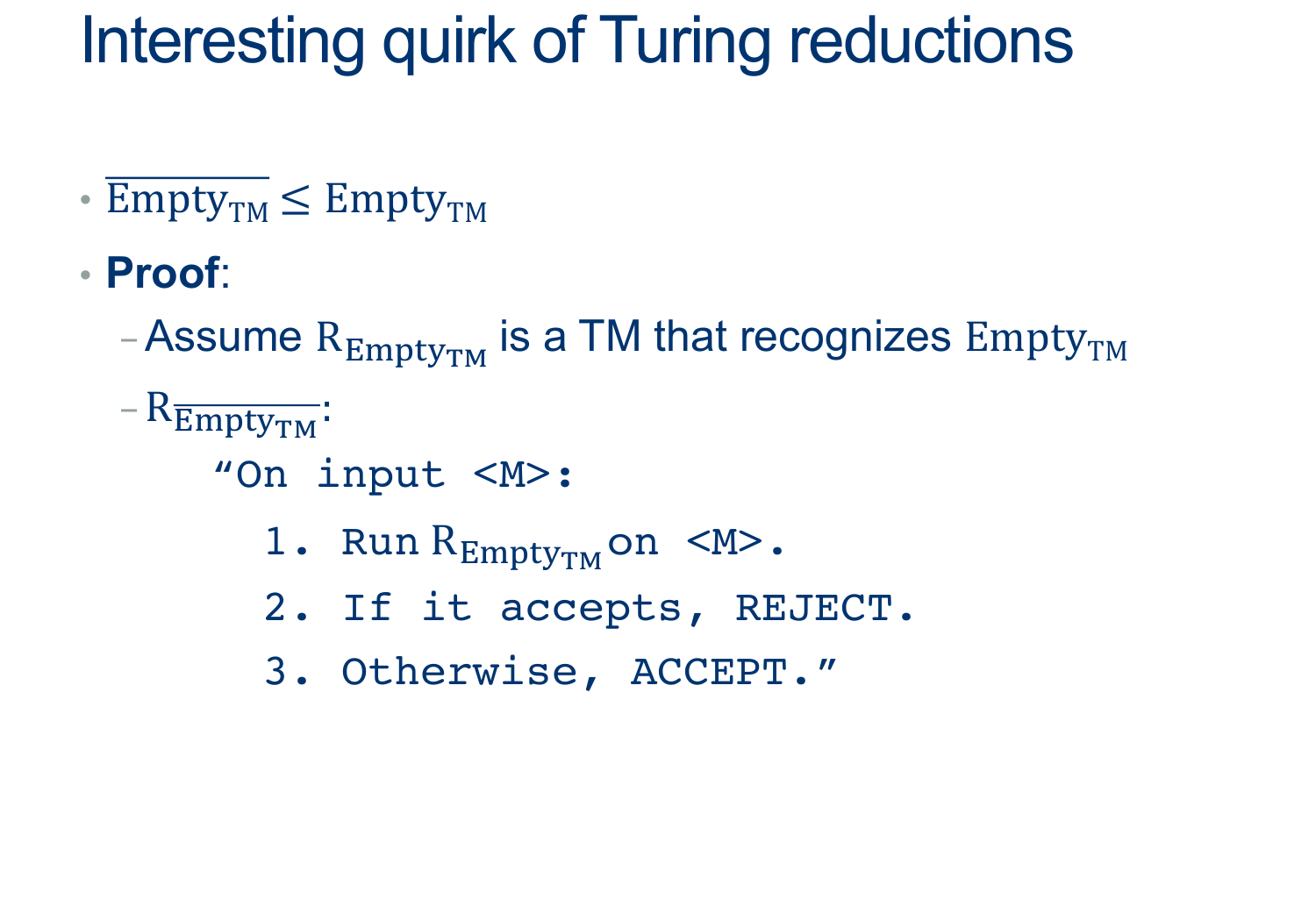

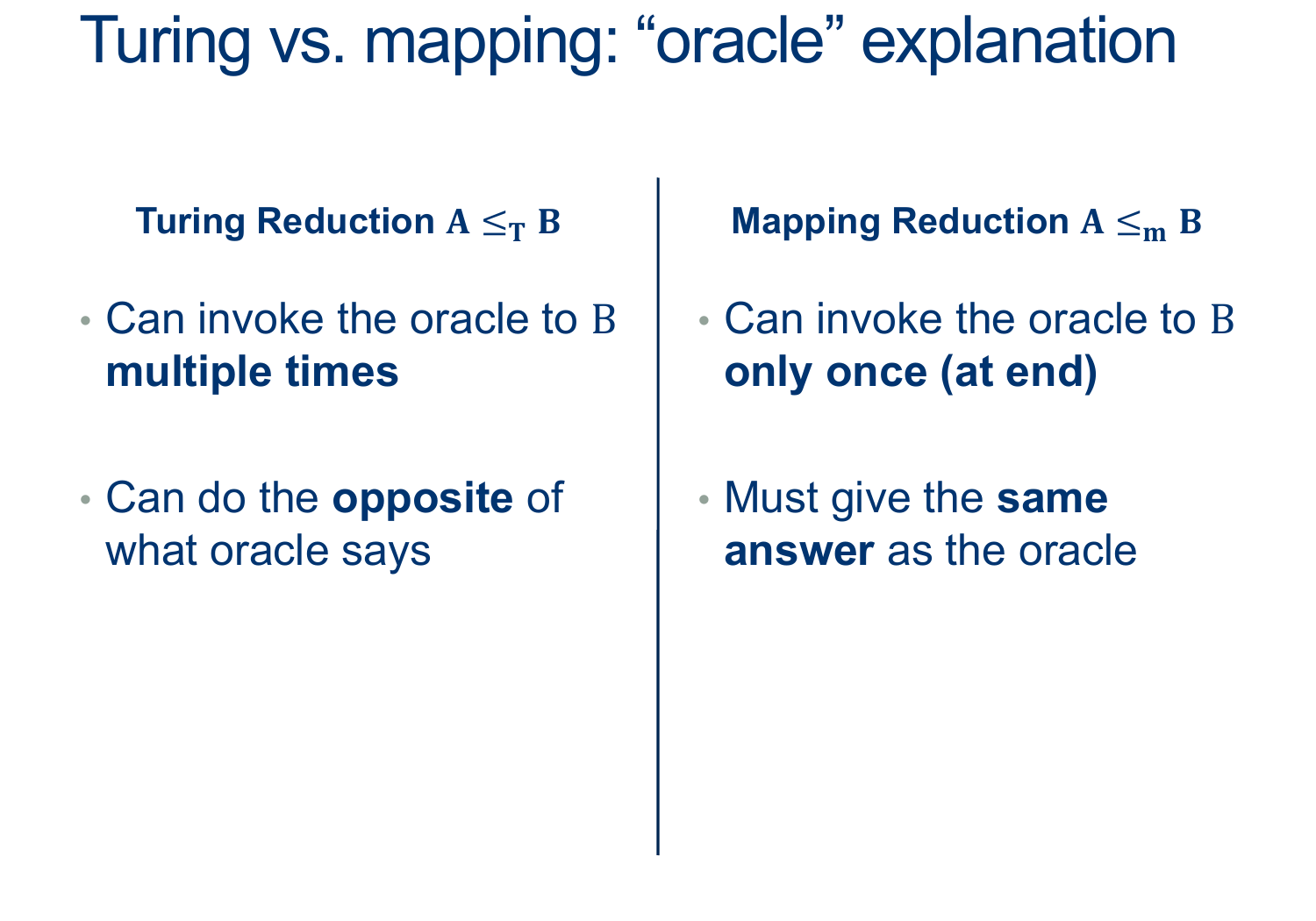

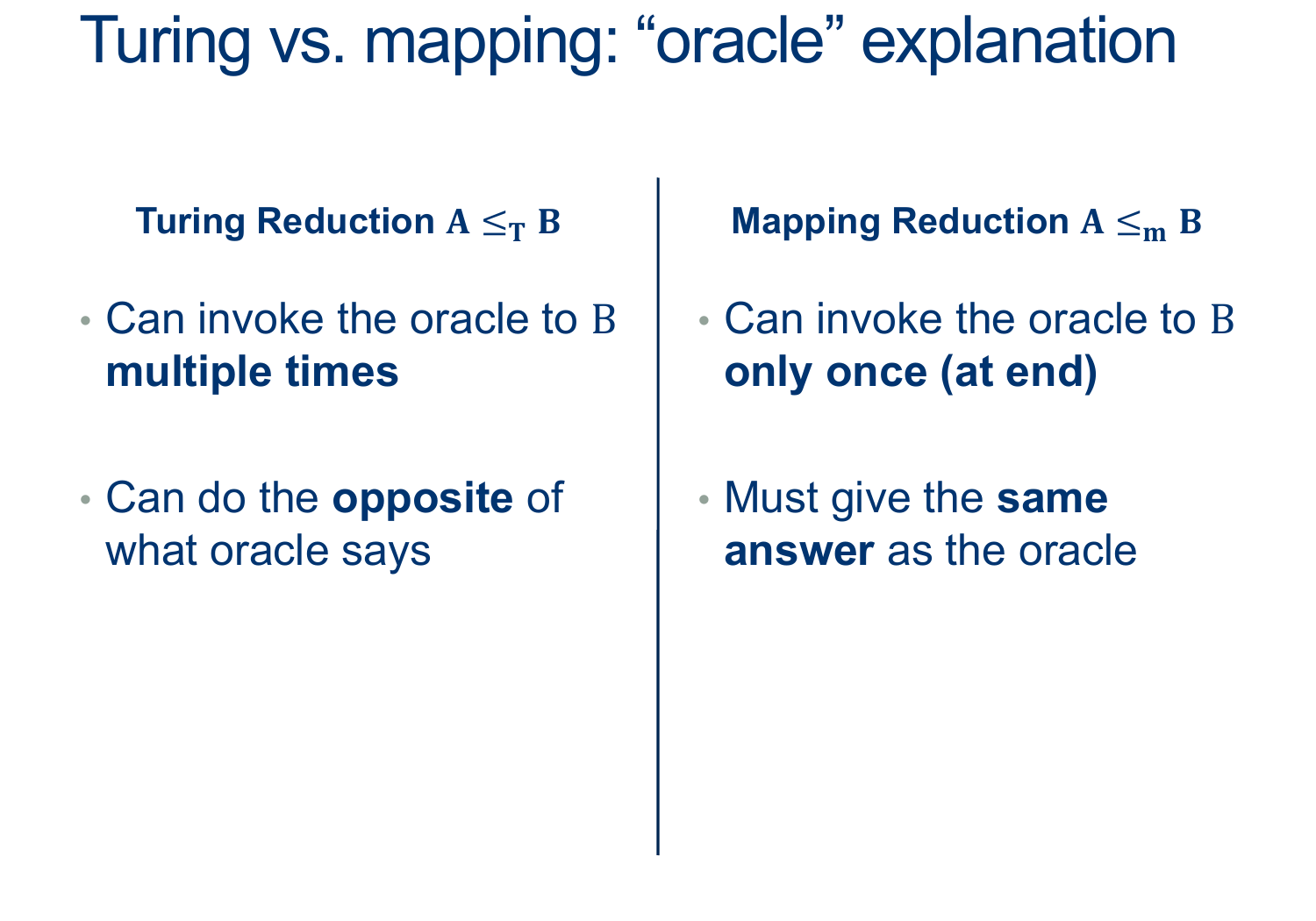

This means our Turing Reduction can’t catch the ordering between languages… nor can we really use it to establish, from its results a clear idea of the class of languages they belong to.

Issue with EMPTY ≤ ¬EMPTY is that the “Domain” of one is complement of the “Domain” of the other!

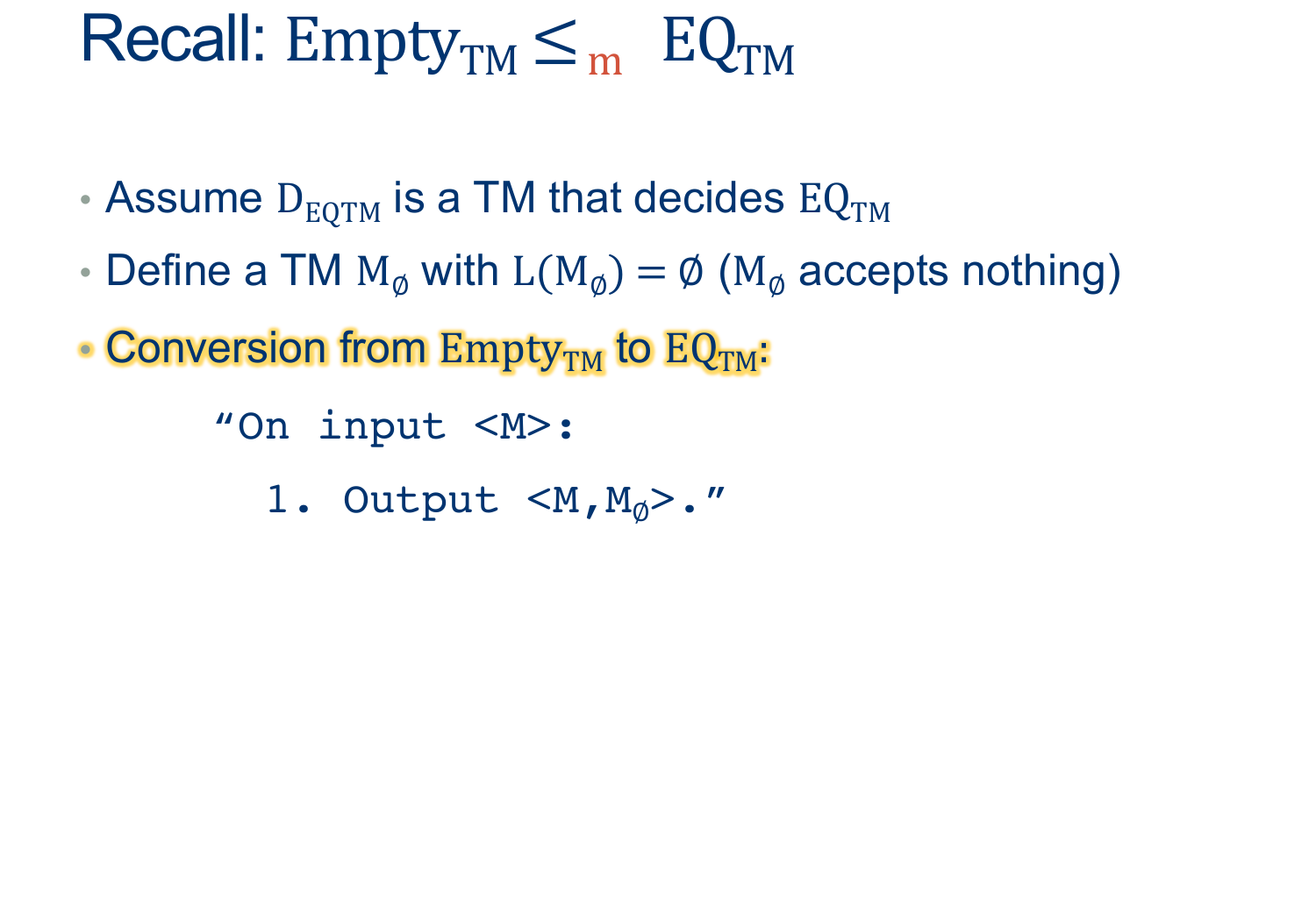

However, we’ve actually seen a STRONGER type of reduction

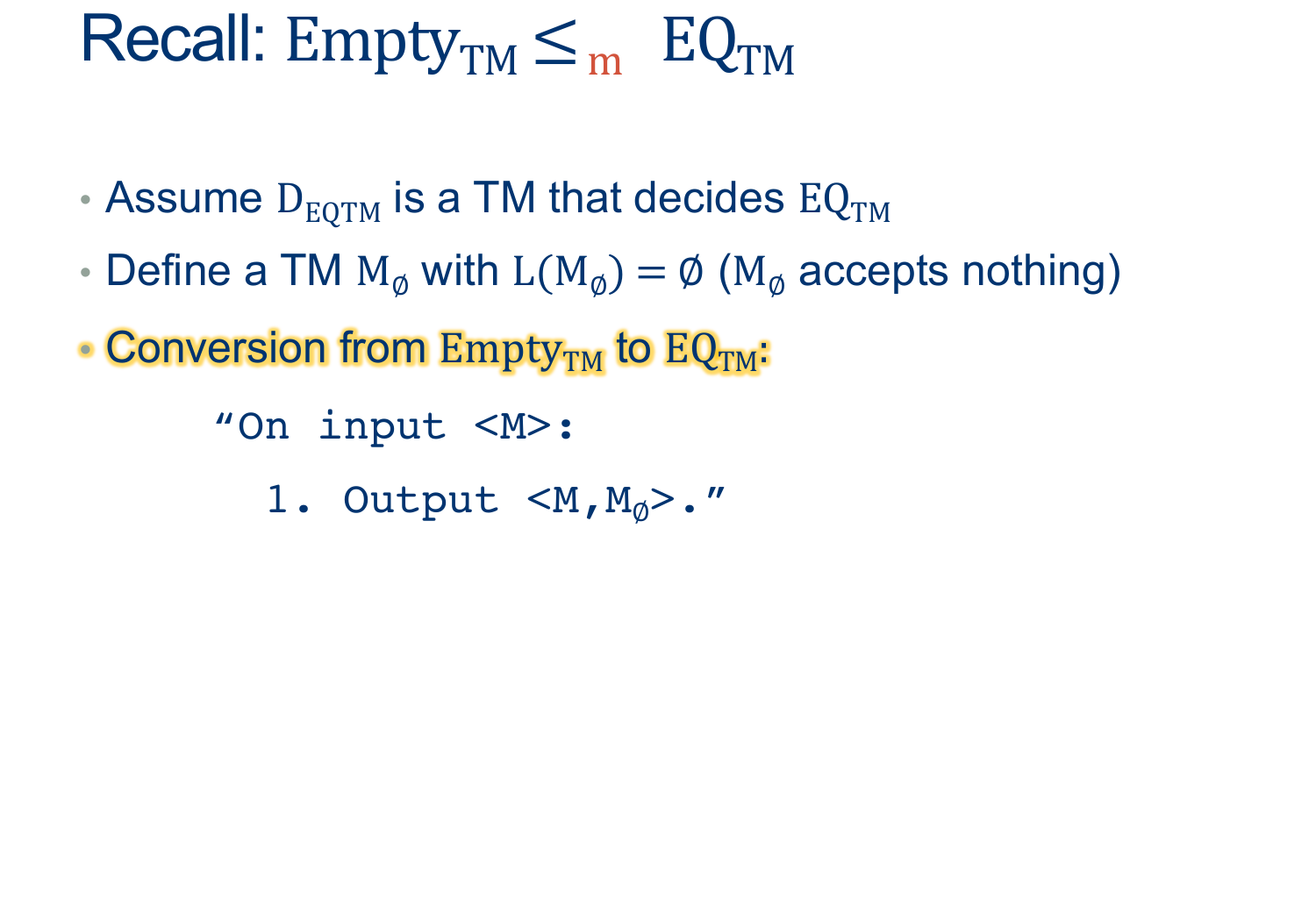

Here, The “Domain” of EMPTY corresponds to the “Domain” of EQ!

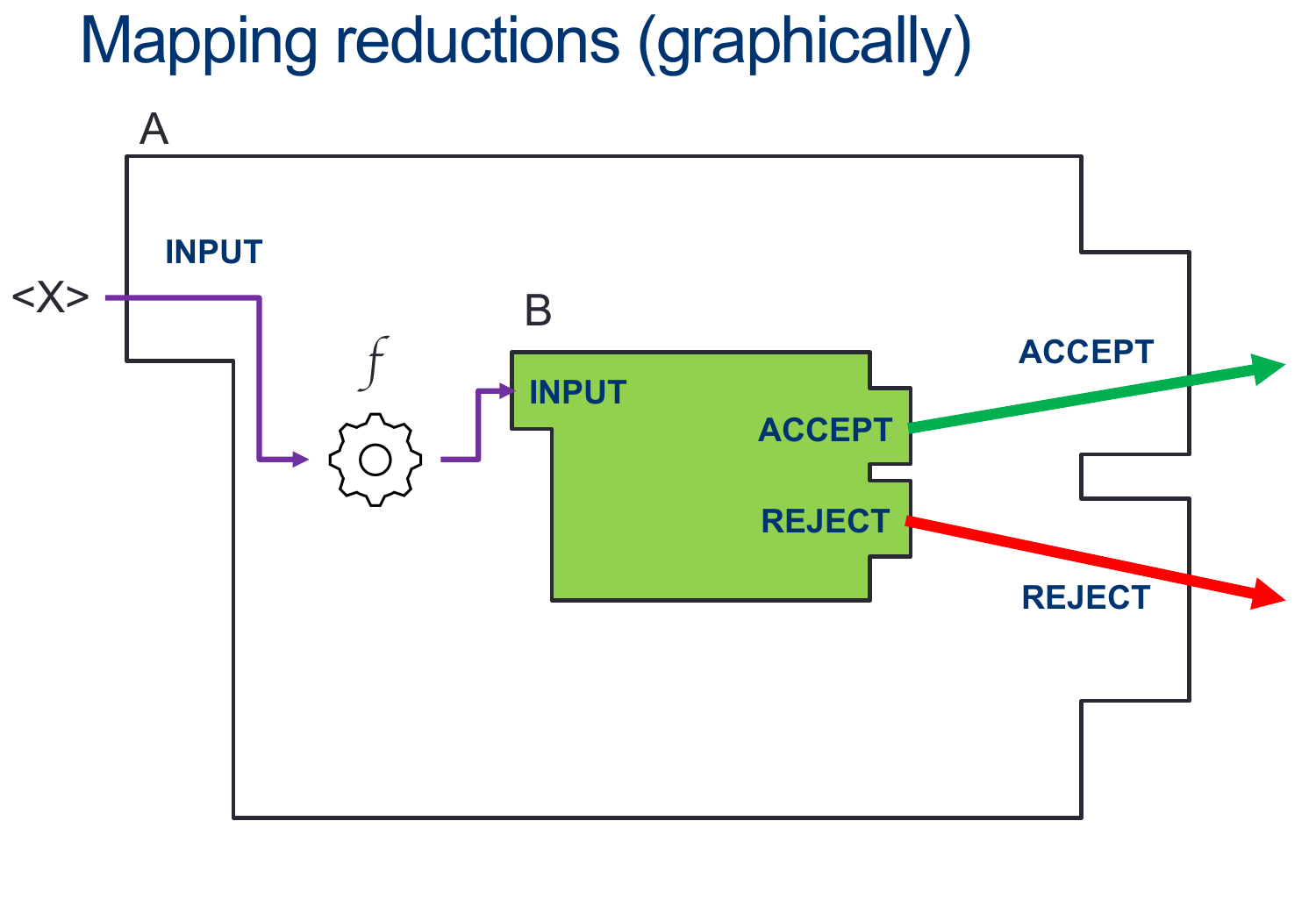

We could rewrite this as a simple conversion from any word in EmptyTM to a word in EQ_TM (and similarly a word not in EmptyTM to a word not in EQ_TM).

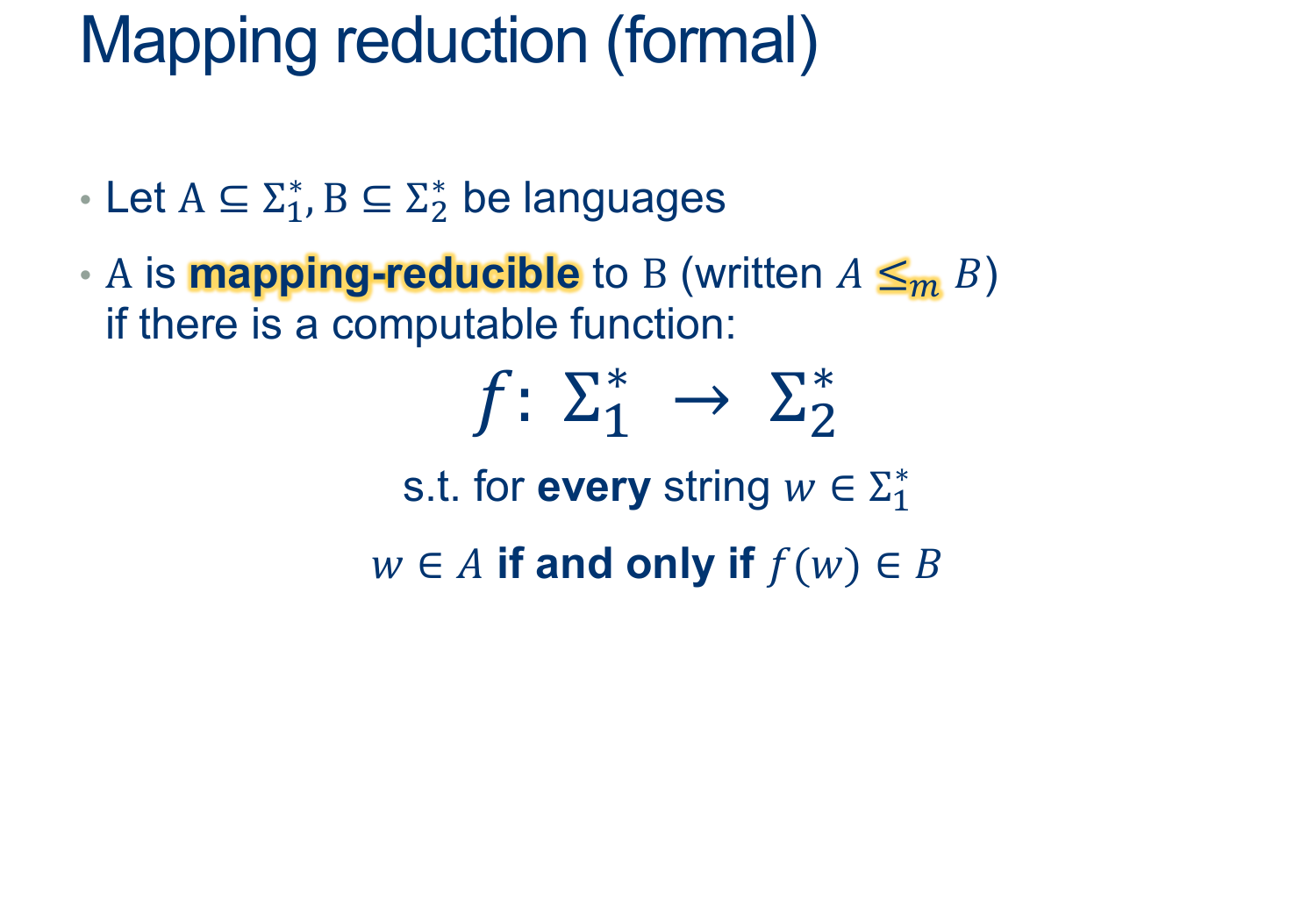

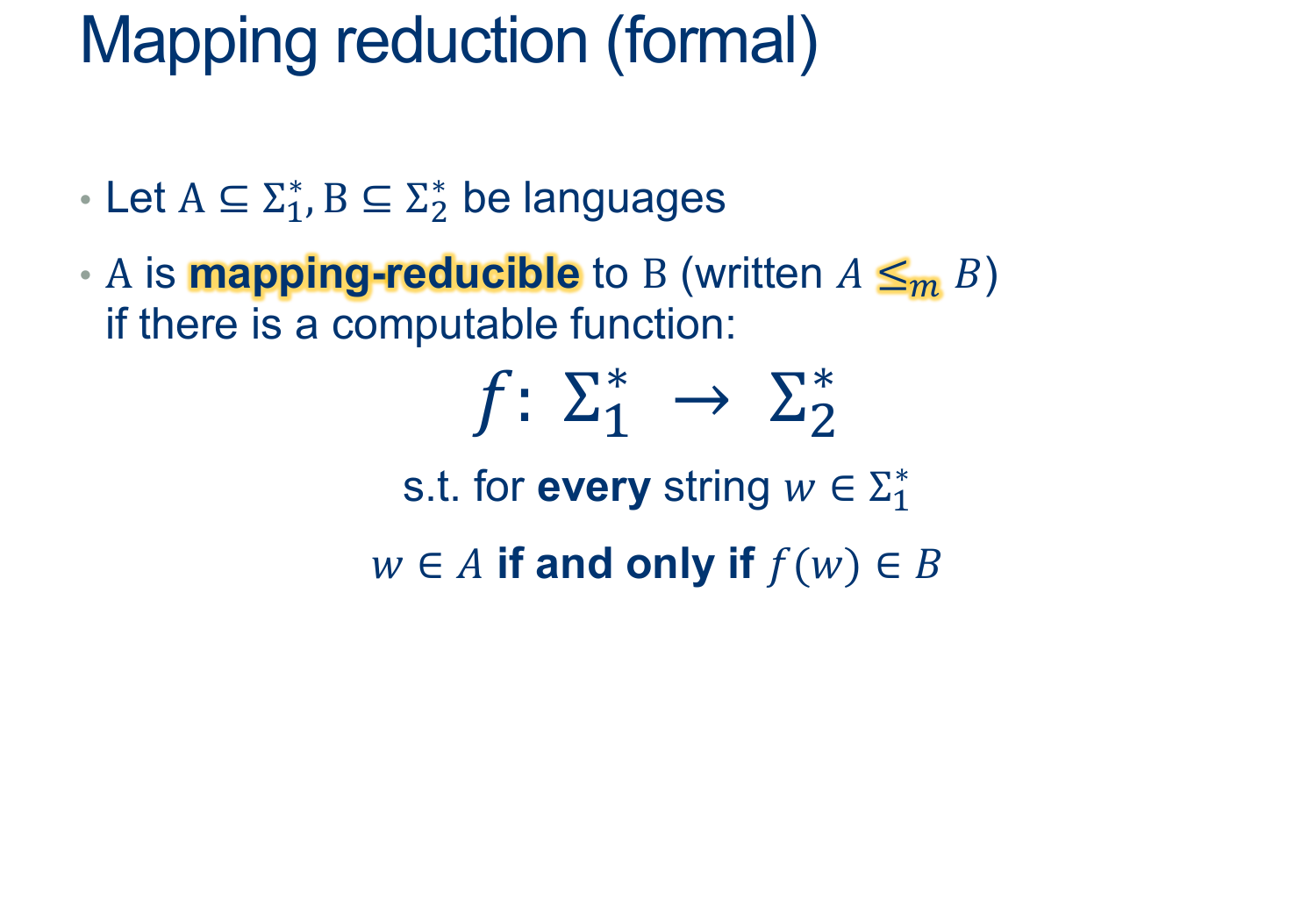

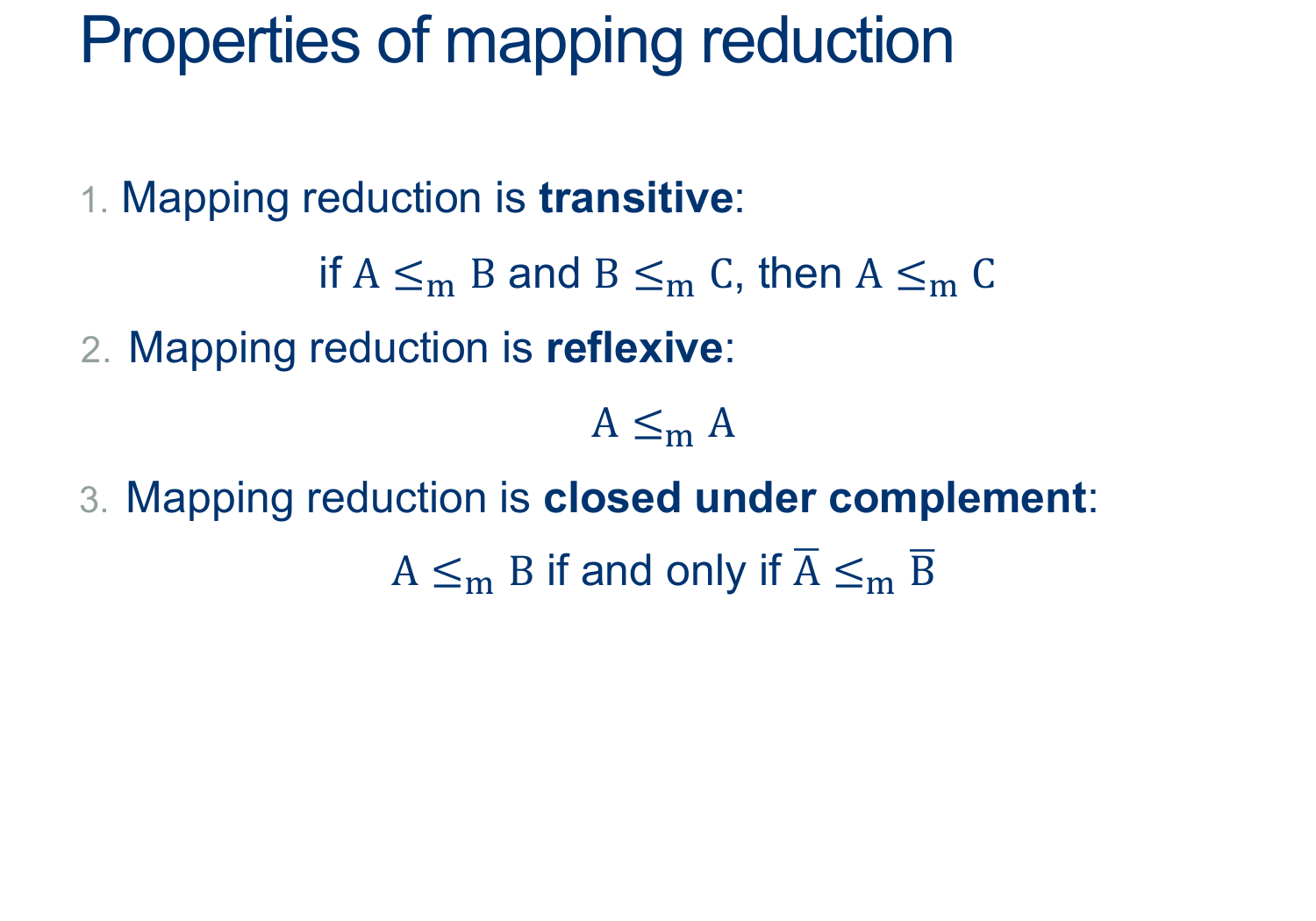

We call this a mapping reduction, and denote it $ \leq_m$

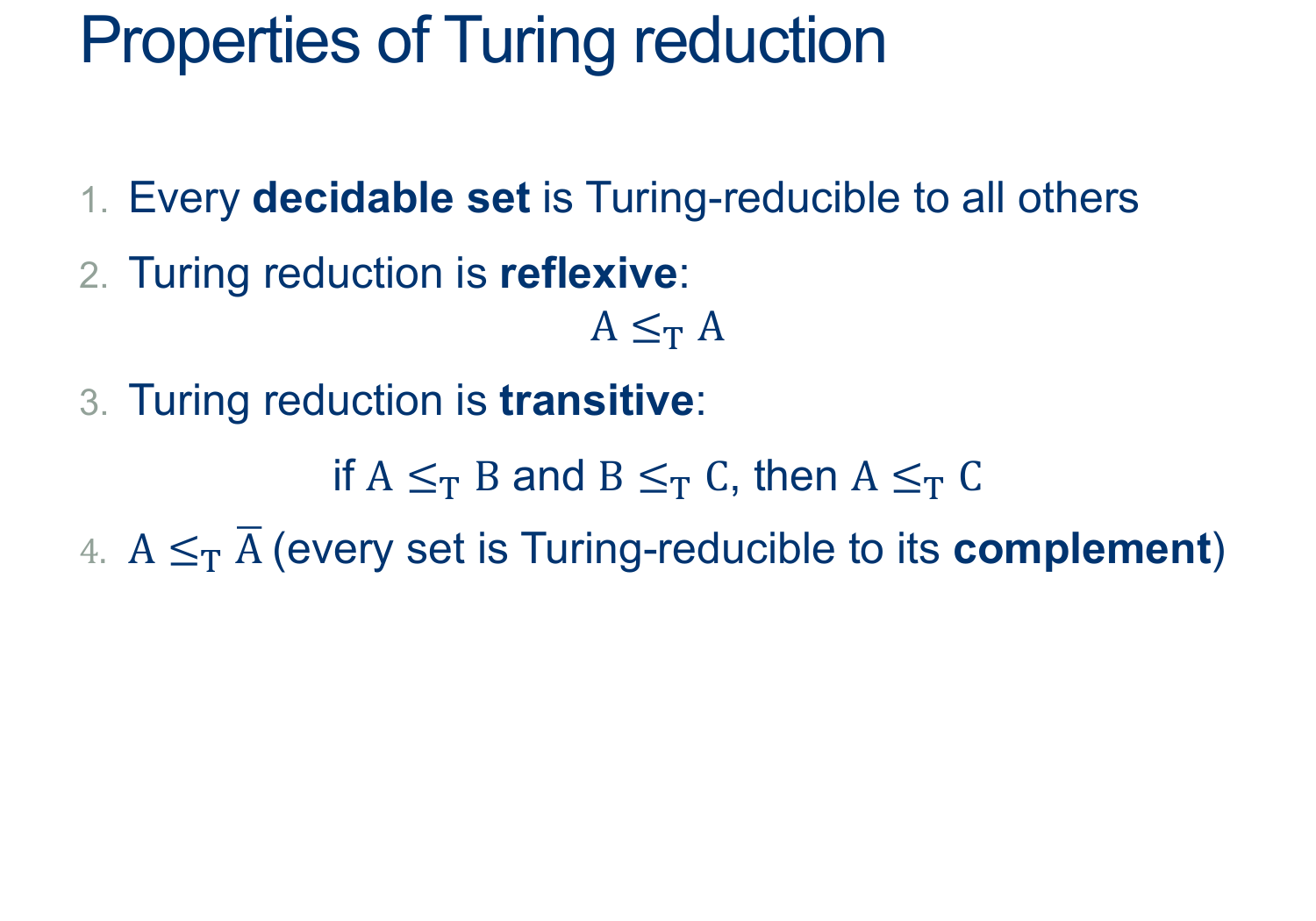

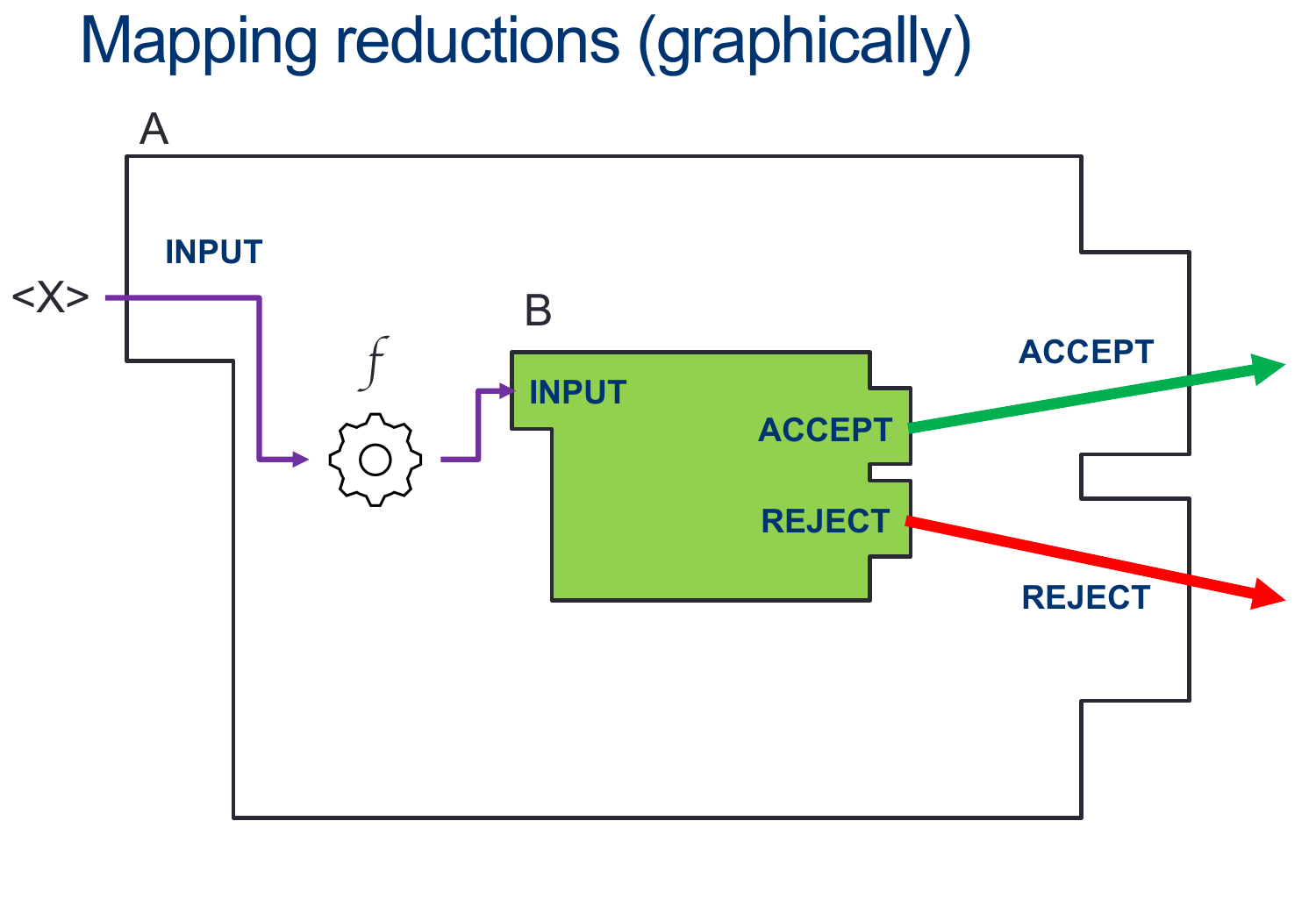

Mapping Reductions

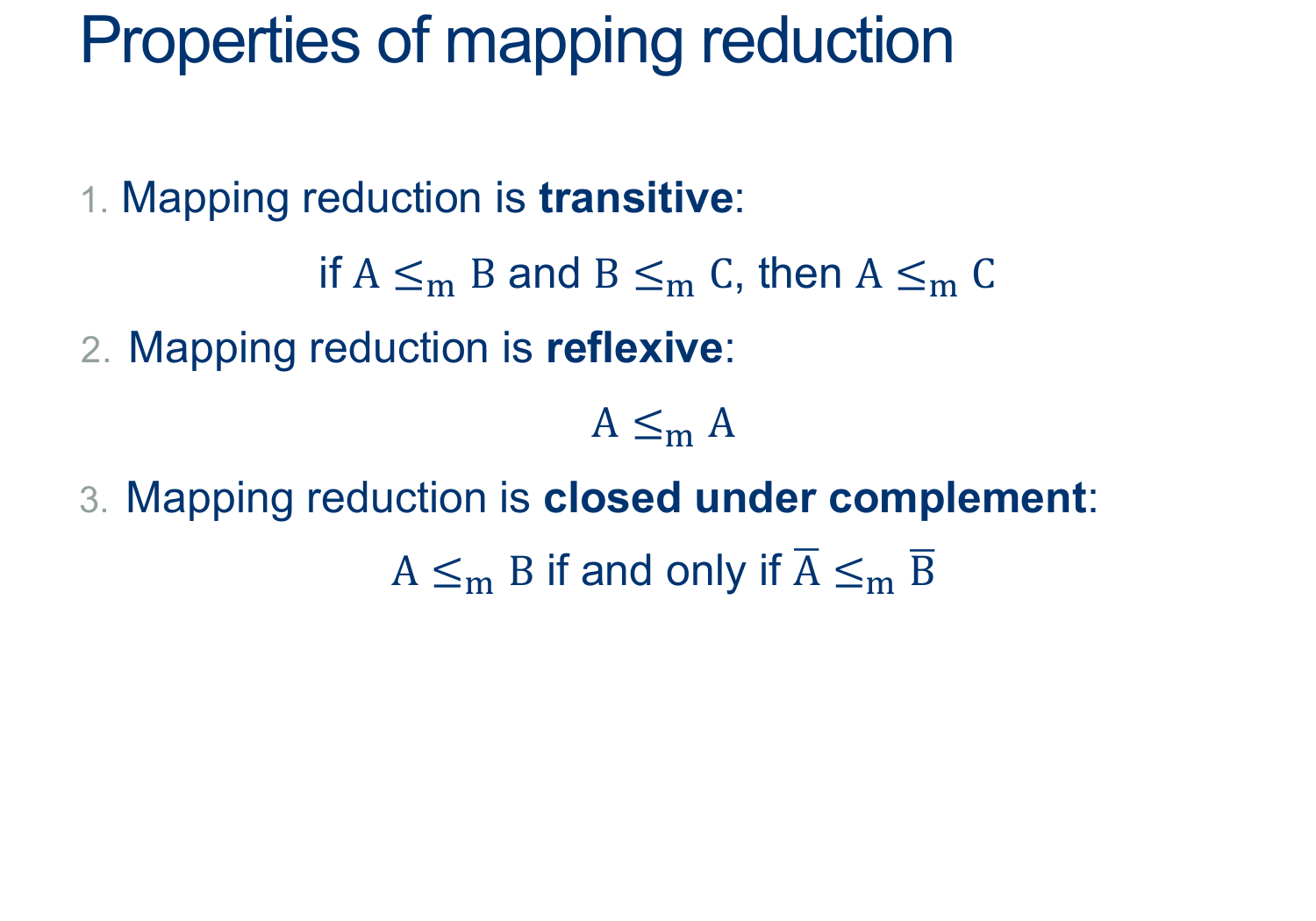

They’re a way for us to relate problems to one another

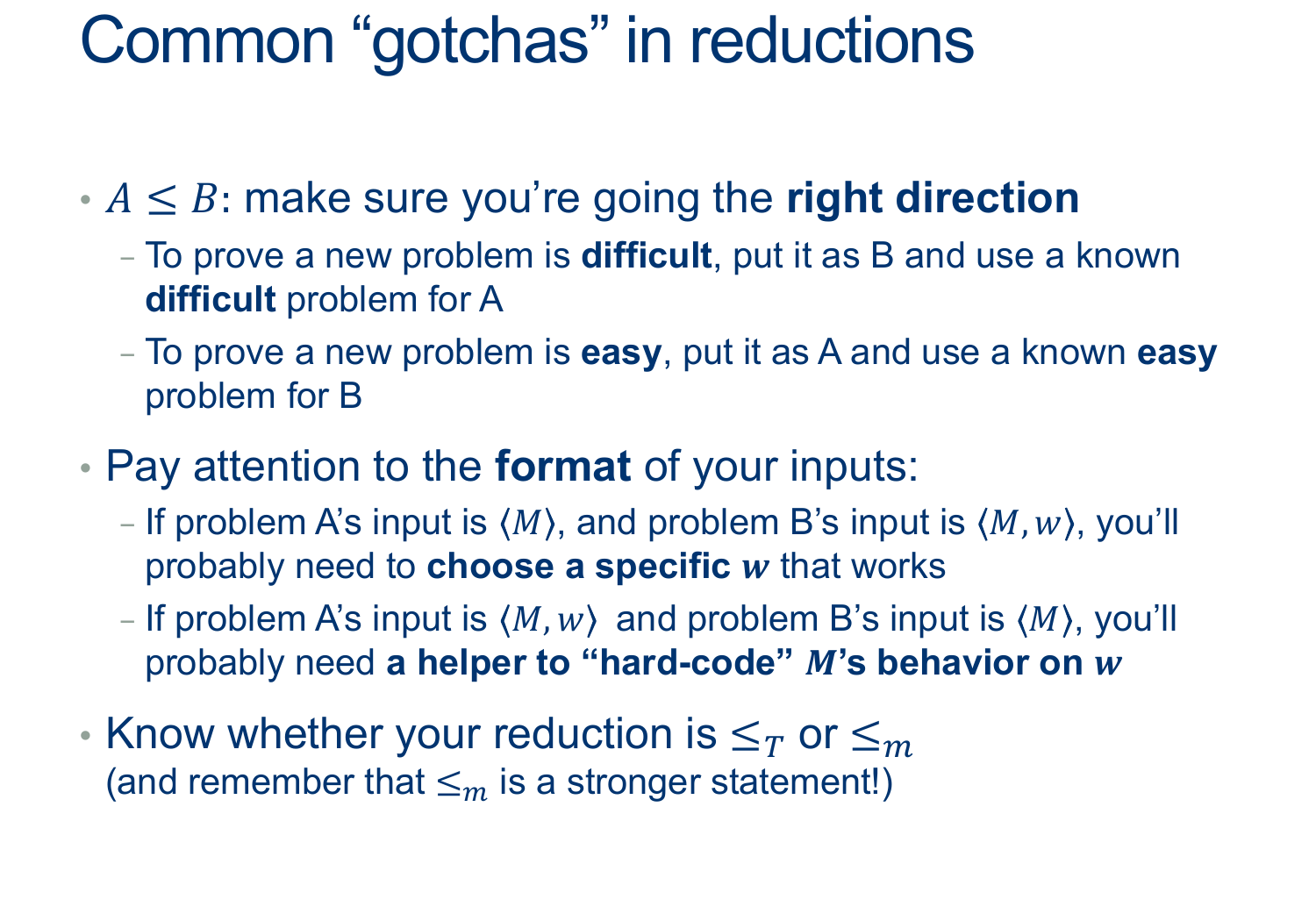

If A reduces to B and B is easy => A is easy too

More common: if A reduces to be and A is hard => B is hard too

We started with ATM (which we proved was undecidable using a big ugly contradiction )

Reduced ATM to HALT (ATM ≤ HALT): we showed that if we had a decider HALT, we could use that to decide ATM (so that means HALT must also be undecidable)

We did the same thing with ATM-01

And EmptyTM

Later, we also showed that if we had a decider for HALT, we could use that to decide EmptyTM

And that if we had a decider for EQ_TM, we could yet again decide EmptyTM (mapping)

Mapping Reducibility and Reductions Conclussion

A Reduction Issuue

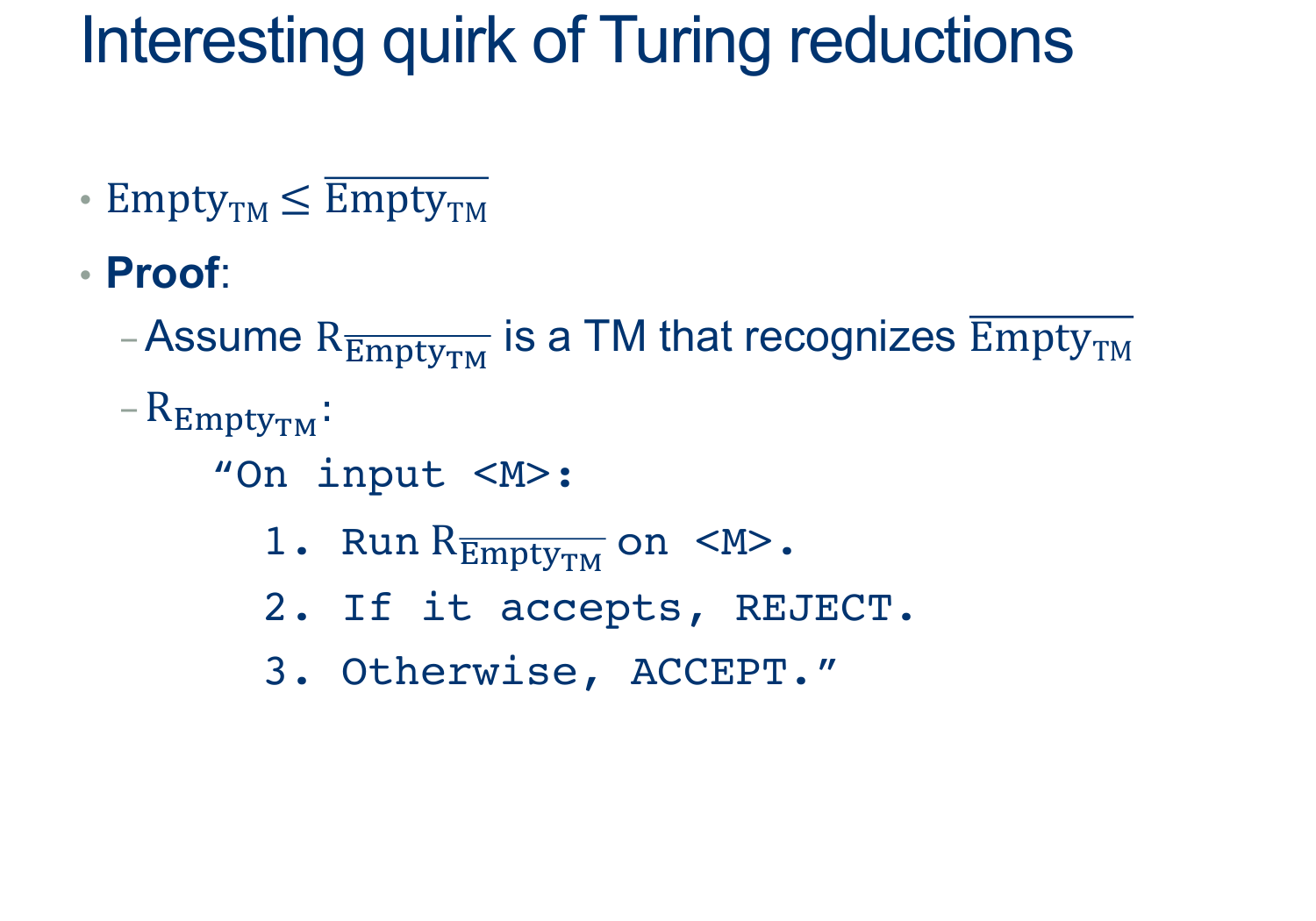

The Emptiness Problem

- Theorem: $\overline{EMPTY-TM}$ is recognizable

- Theorem: $EMPTY-TM$ is undecidable

- Corollary: $EMPTY-TM$is unrecognizable

- Proof: If $\overline{EMPTY-TM}$ and $EMPTY-TM$ recognizable,

- that would imply $EMPTY-TM$ is decidable

This means our Turing Reduction Can’t catch if the fact that we’re reducing outside the same class of languages

Issue with EMPTY ≤ ¬EMPTY is that the “Domain” of one is complement of the “Domain” of the other!

However, we’ve actually seen a STRONGER type of reduction

Here, The “Domain” of EMPTY corresponds to the “Domain” of EQ!

We could rewrite this as a simple conversion:

from any word in EmptyTM to a word in EQ_TM (and similarly a word not in EmptyTM to a word not in EQ_TM).

We call this a mapping reduction, and denote it $ \leq_m$

Mapping Reductions

They’re a way for us to relate problems to one another

If A reduces to B and B is easy => A is easy too

More common: if A reduces to be and A is hard => B is hard too

We started with ATM (which we proved was undecidable using a big ugly contradiction )

Reduced ATM to HALT (ATM ≤ HALT): we showed that if we had a decider HALT, we could use that to decide ATM

(so that means HALT must also be undecidable)

We did the same thing with ATM-01

And EmptyTM

Later, we also showed that if we had a decider for HALT, we could use that to decide EmptyTM

And that if we had a decider for EQ_TM, we could yet again decide EmptyTM (mapping)

Activity 1 [2 minutes] How would you do this reduction?: (Wait; then Click)

(Wait; then Click)

$$HALT \leq_m SOMETIMES-HALTS$$ We want to show that we can take any input and transform it such that: if the input was a word in HALT $(< M,w>)$, the output is a word $(< M>)$ in SOMETIMES-HALTS if the input was NOT a word in HALT, the output is NOT a word in SOMETIMES-HALTS This suggests that we want to build a helper machine that “amplifies” the behavior of M on w: $$ \begin{align*} &D_{HALT}:\\ & \text{ On input $ < M,w > $ }:\\ & \text{ Create (but don't run) $HELPER_{M,w}$ such that}\\ & \quad \text{ On input $ < X > $ }:\\ & \quad \quad \text{ Ignore $ < X > $ }\\ & \quad \quad \text{ Run M on w ADWID}\\ & \text{ Now Run $D_{S-H}$ on input $ < HELPER_{M,w} > $ ADWID}\\ \end{align*} $$ The only way the helper halts is if M halts on w (if this is the case, it halts on EVERY input). Otherwise, it loops. In other words, if $< M,w>$ was in HALT, then the helper will be in SOMETIMES-HALTS, and if $< M,w>$ is NOT in HALT, then the helper won’t be in SOMETIMES-HALT. Thus, we’ve defined a mapping that from problems in HALT to problems in SOMETIMES-HALTS, proving that SOMETIMES-HALTS is at least as difficult as HAL, and so must be undecidable.