Lecture Notes 11: Context-Free Grammars

Outline

This class we’ll discuss:

- Perspectives on simple machines

- Properties of Regular Languages

- Looking ahead: Context-Free Grammars

- CFG examples

A Slideshow:

GUIDED NOTES (Optional)

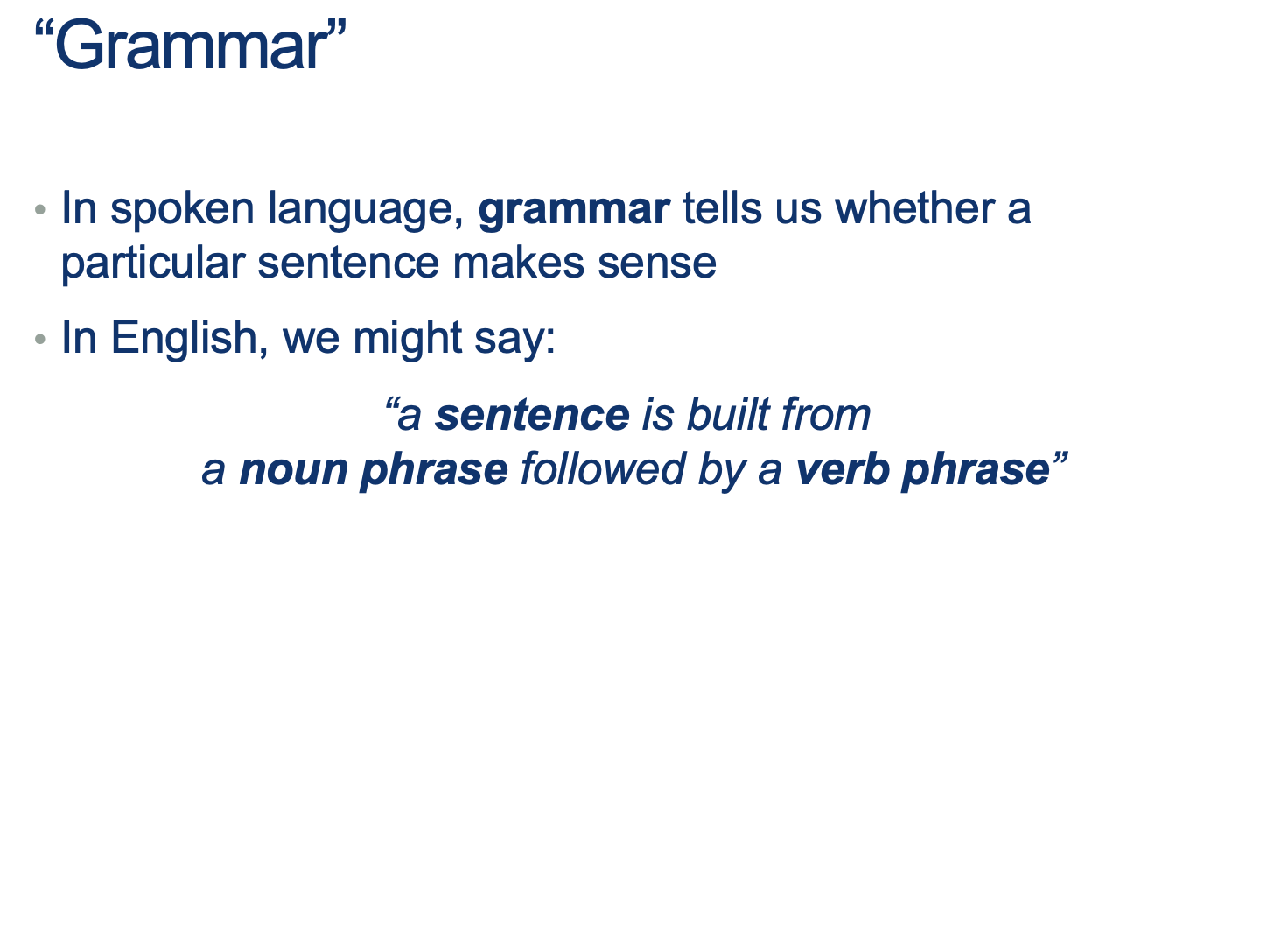

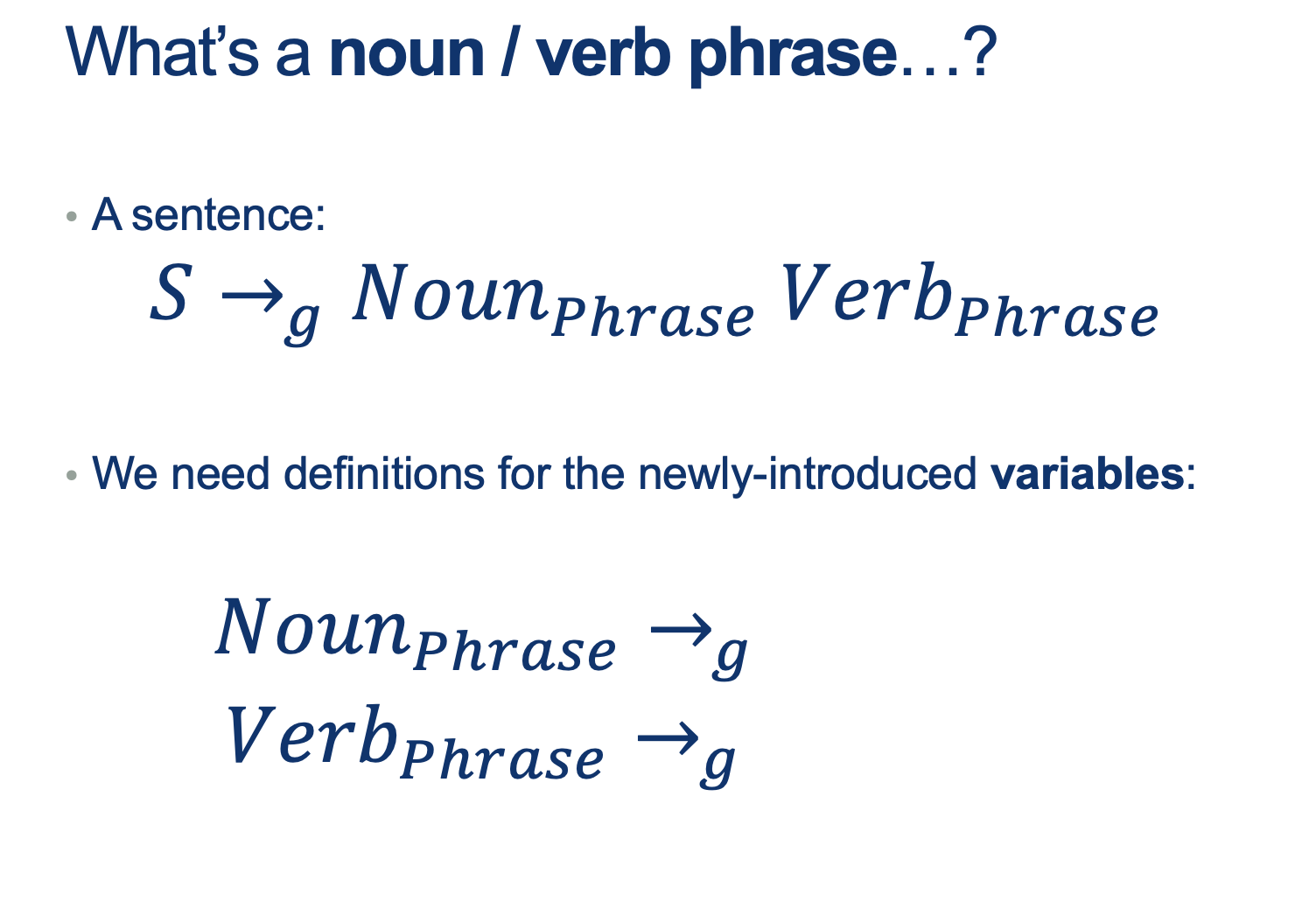

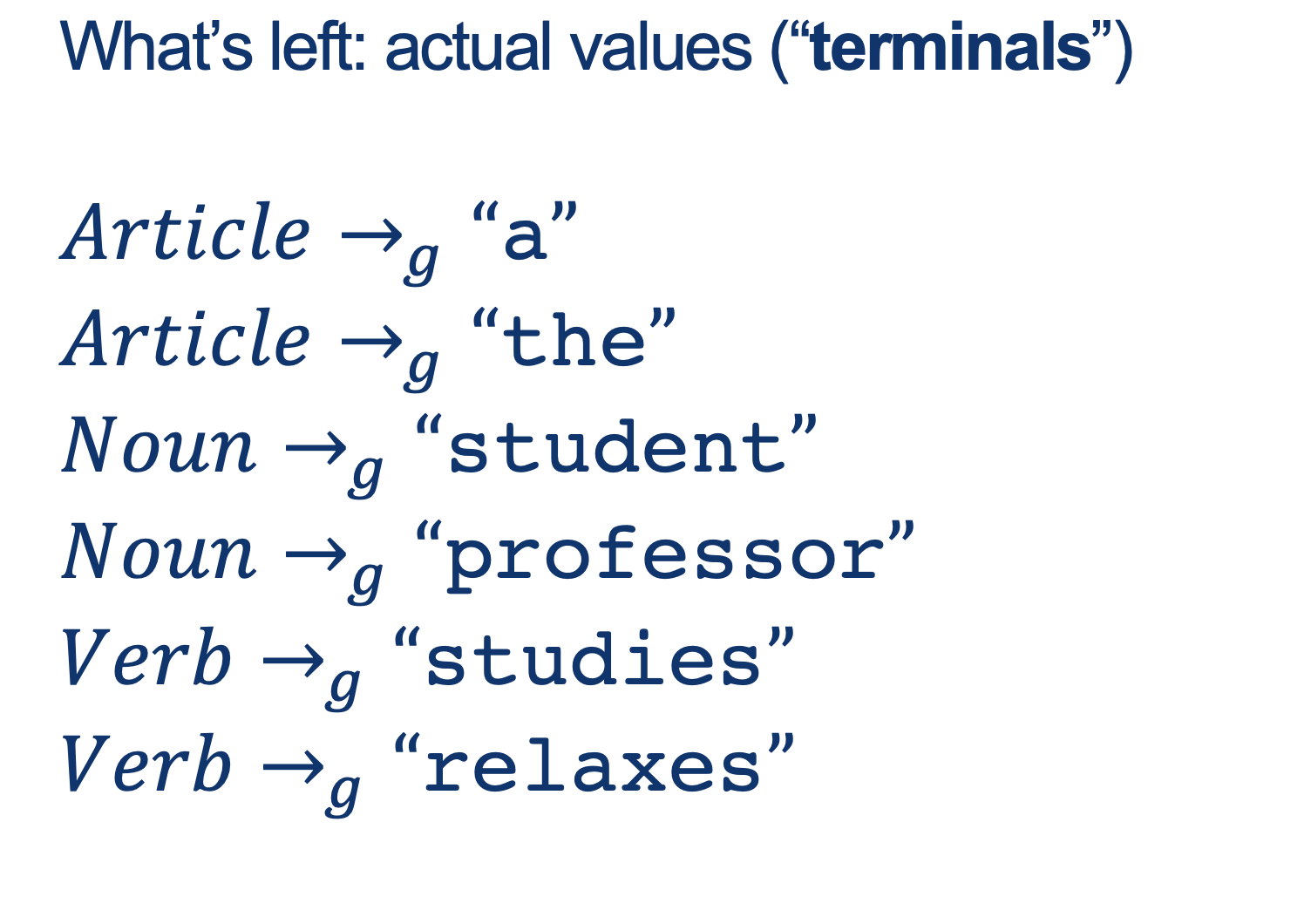

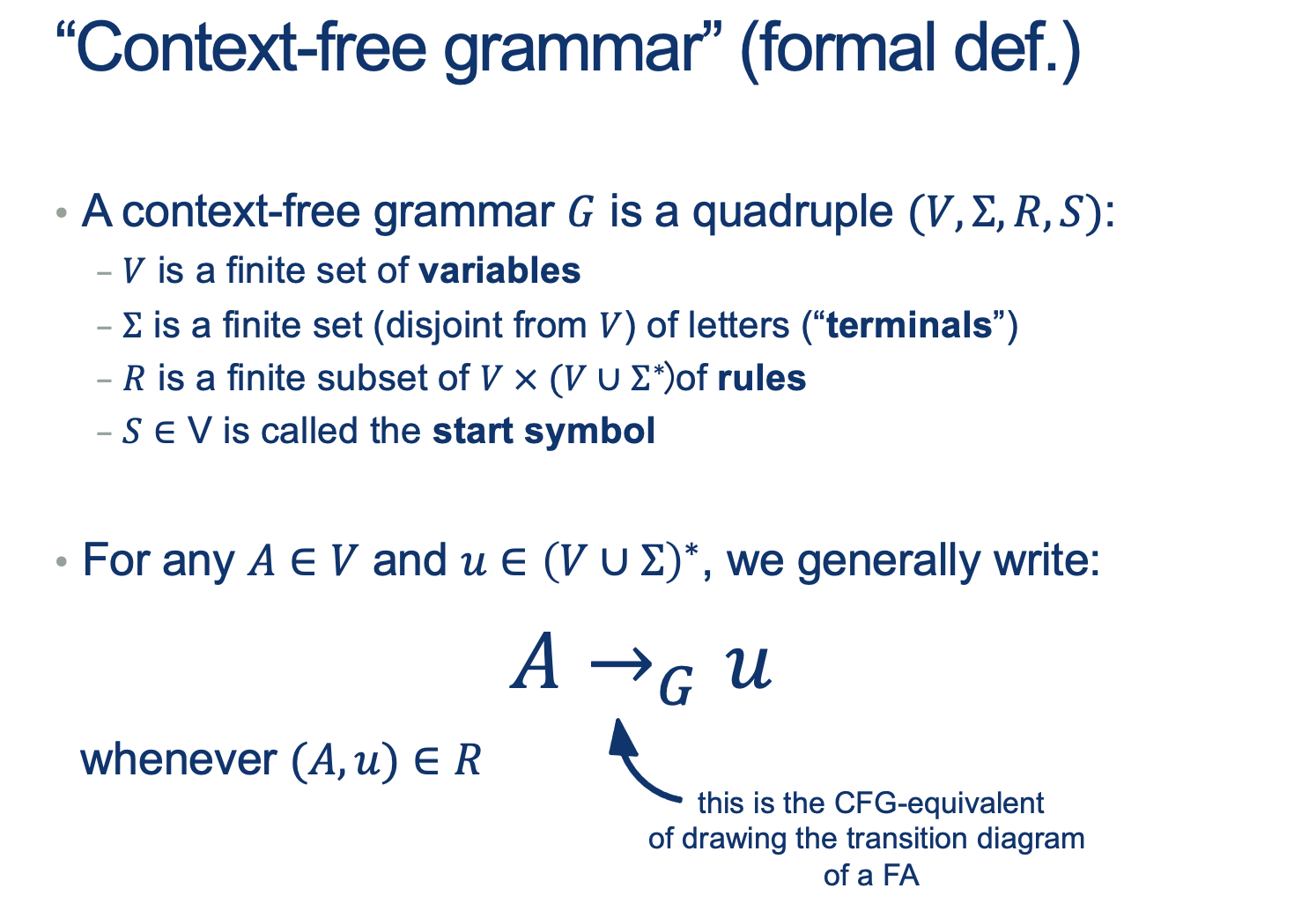

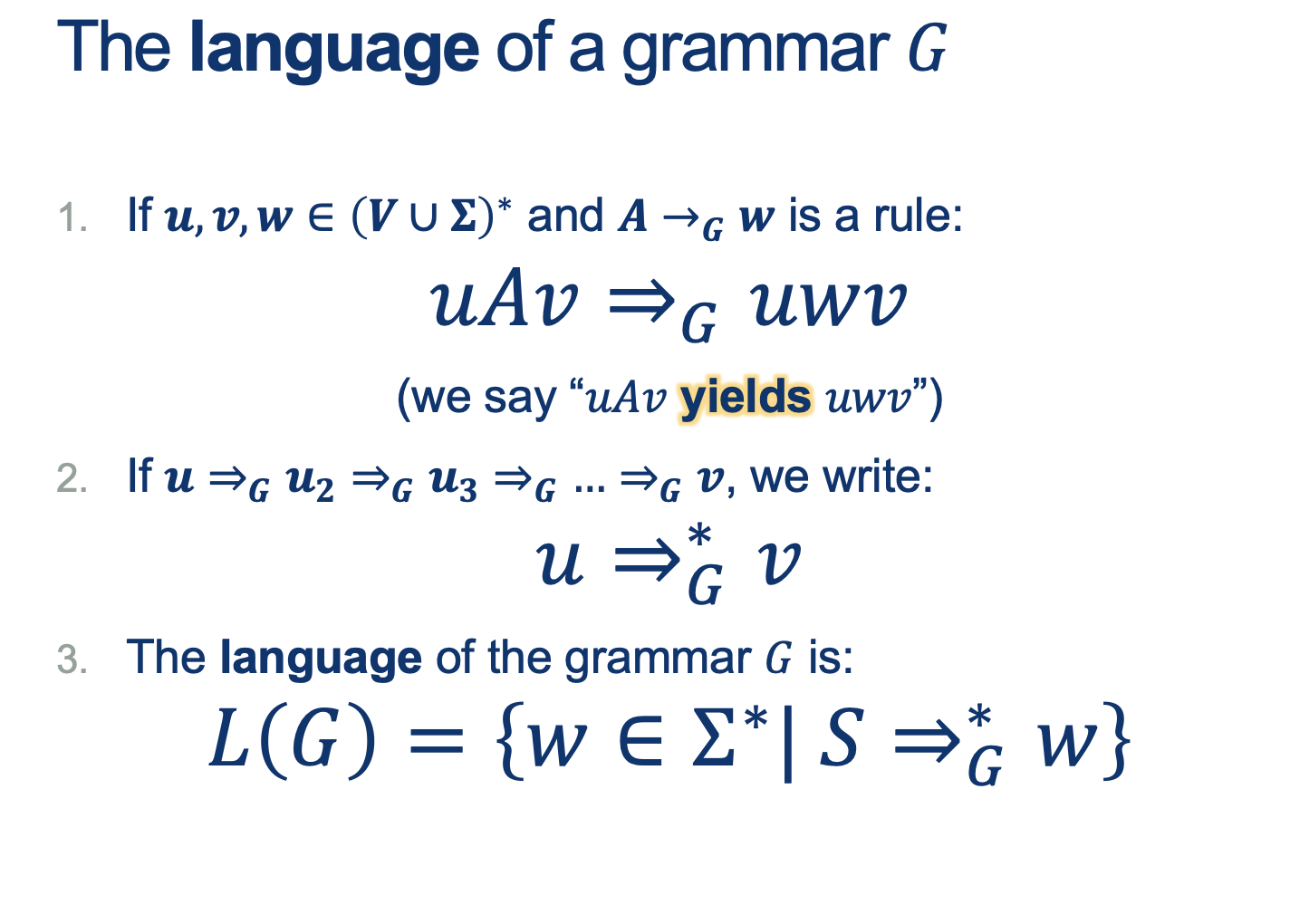

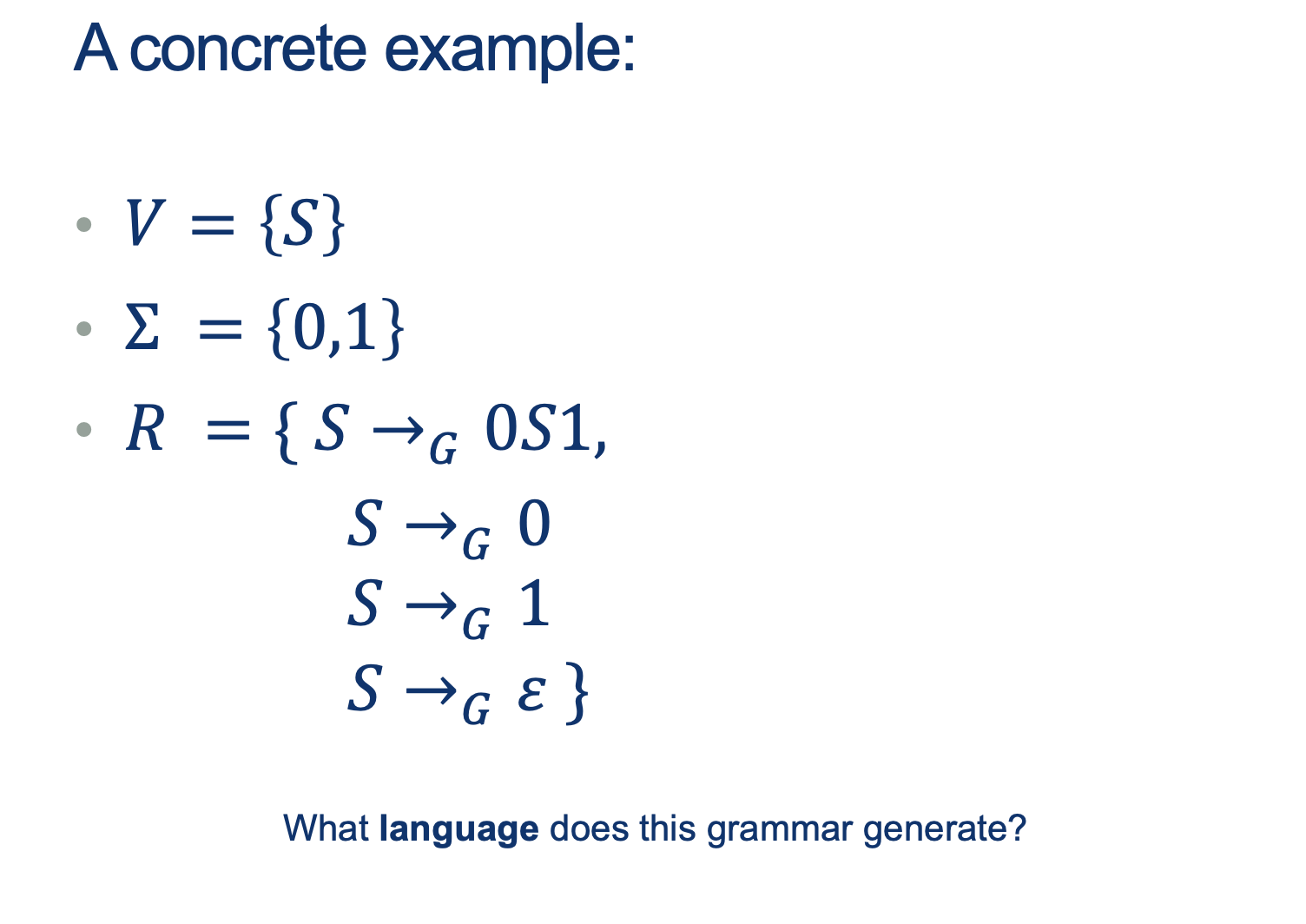

Intro: Context-Free Grammar

EQ, HALF, PAL

Finite automata and regular expressions are limited

They both only match patterns that can be described by reaching L to R

Some patterns are more interesting…

Seems like PAL lives really close to Regular: there’s a structure to the words that’s ALMOST regular… but the pattern is in the middle.

How about EQ?

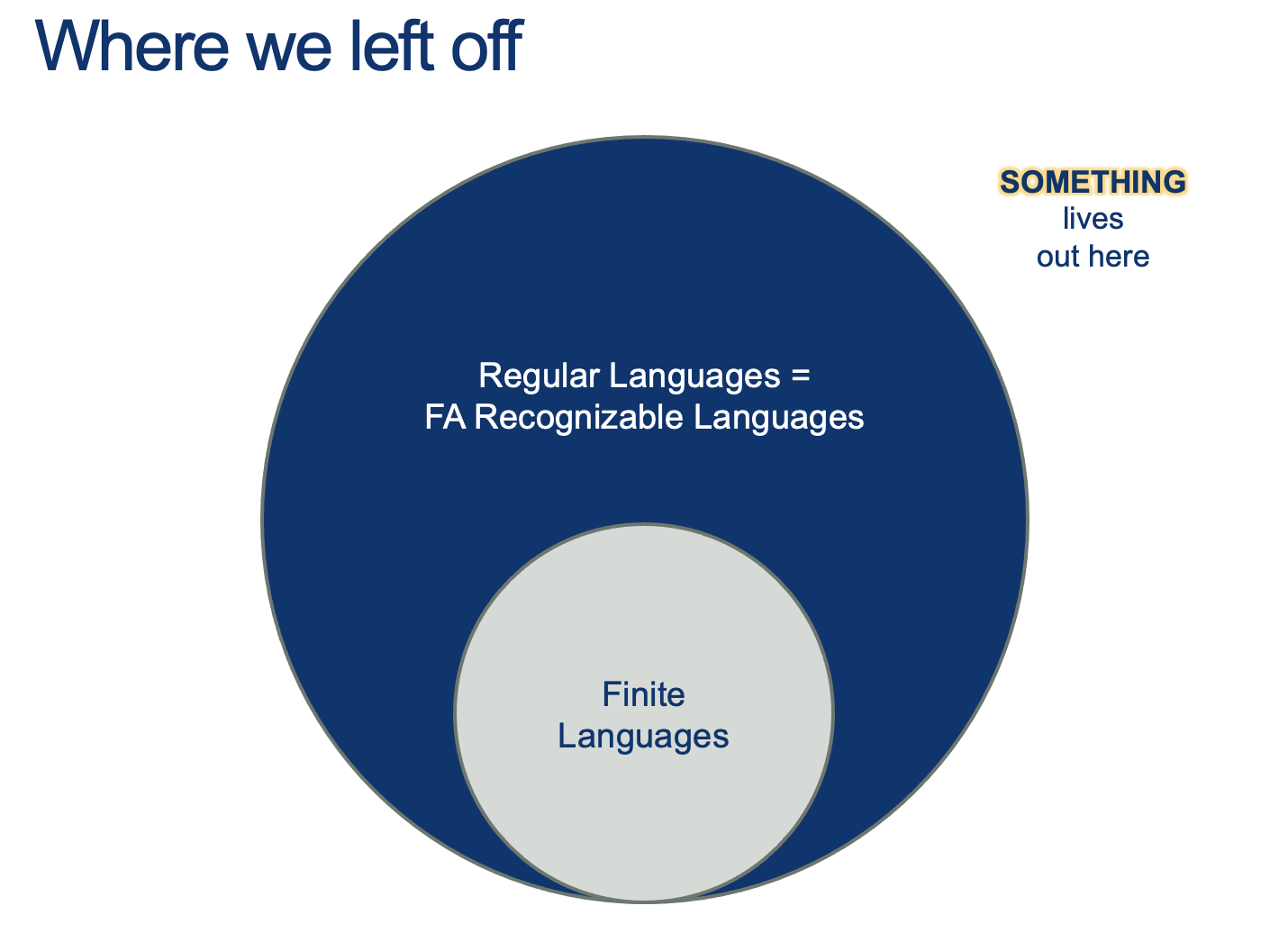

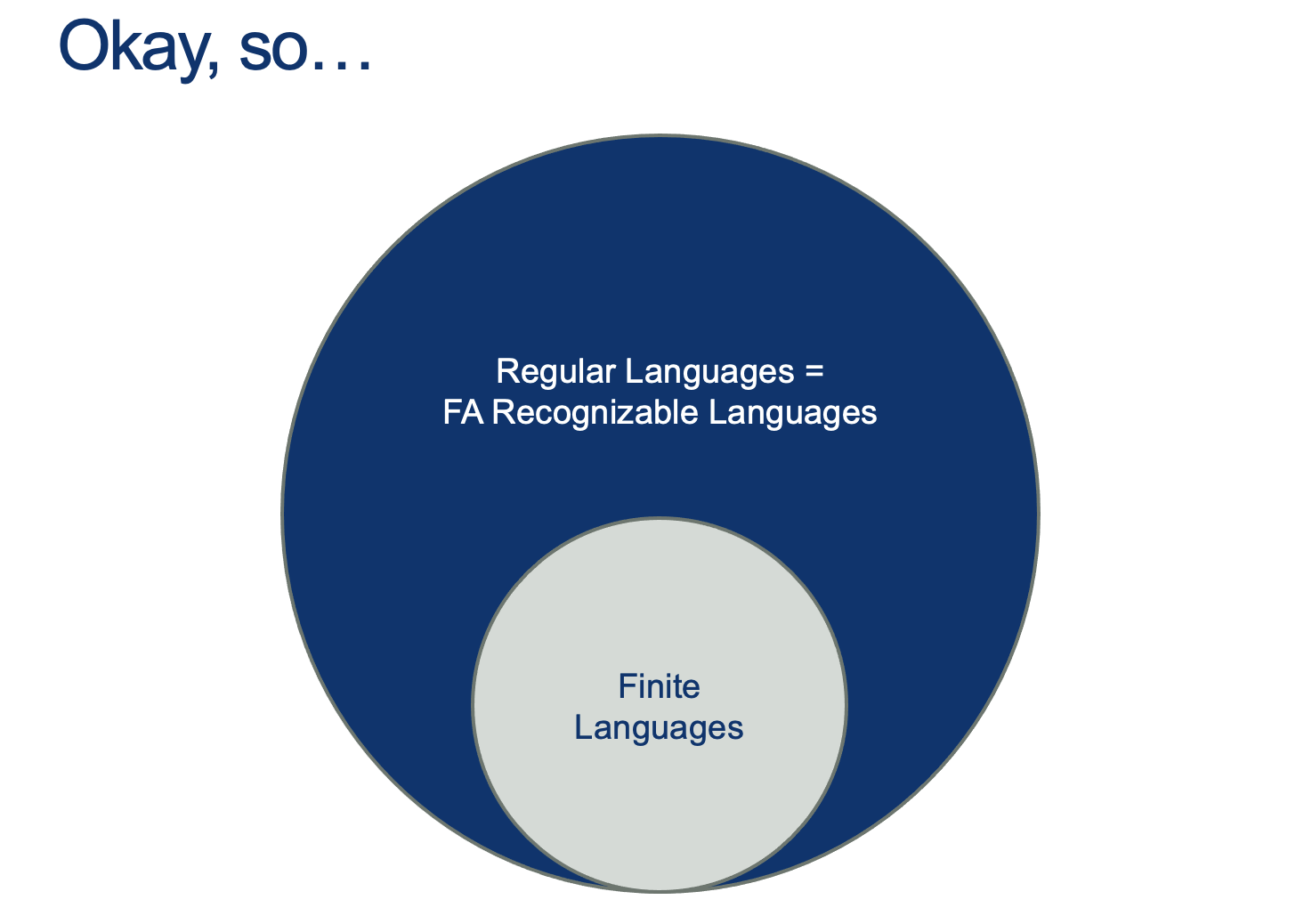

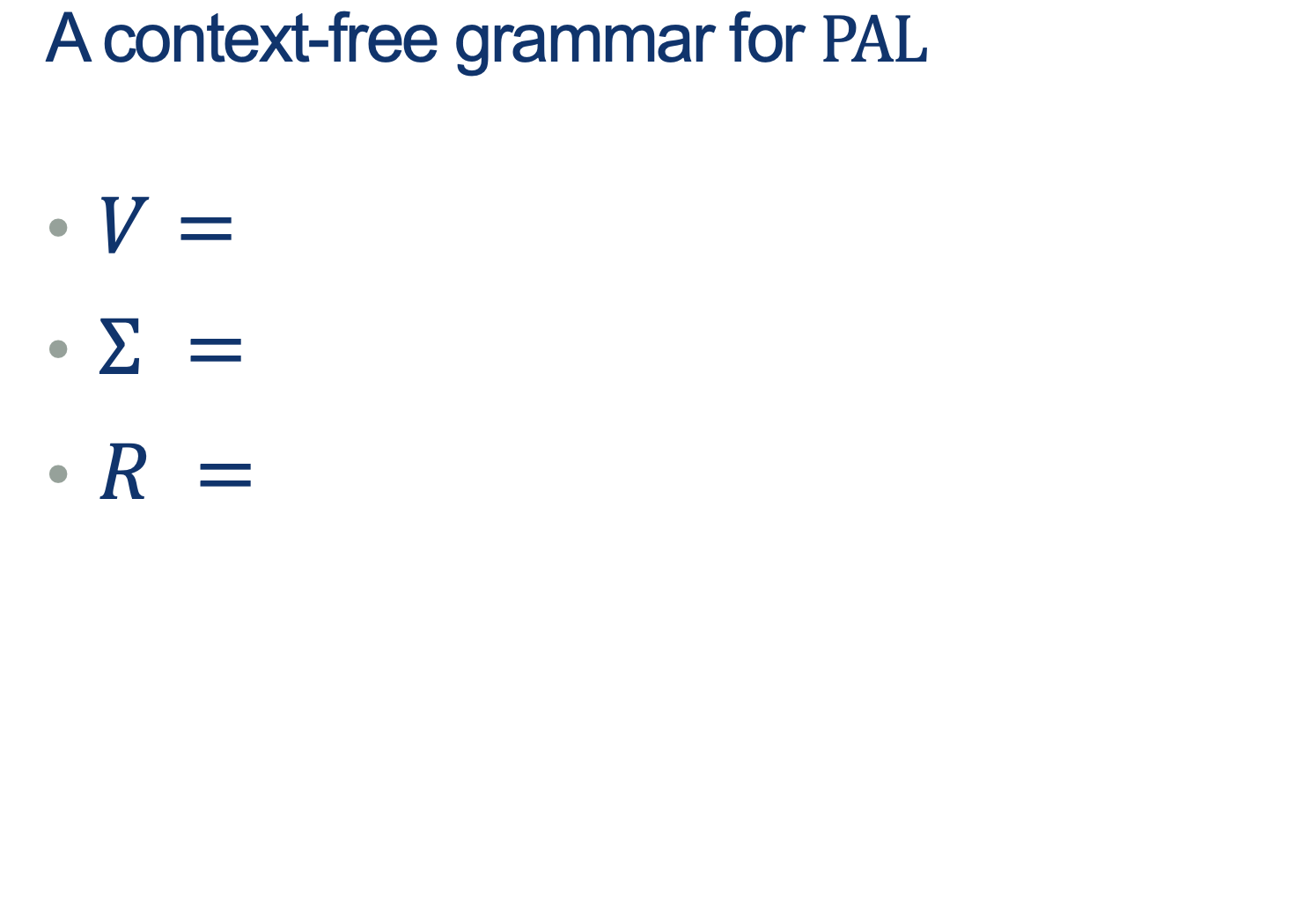

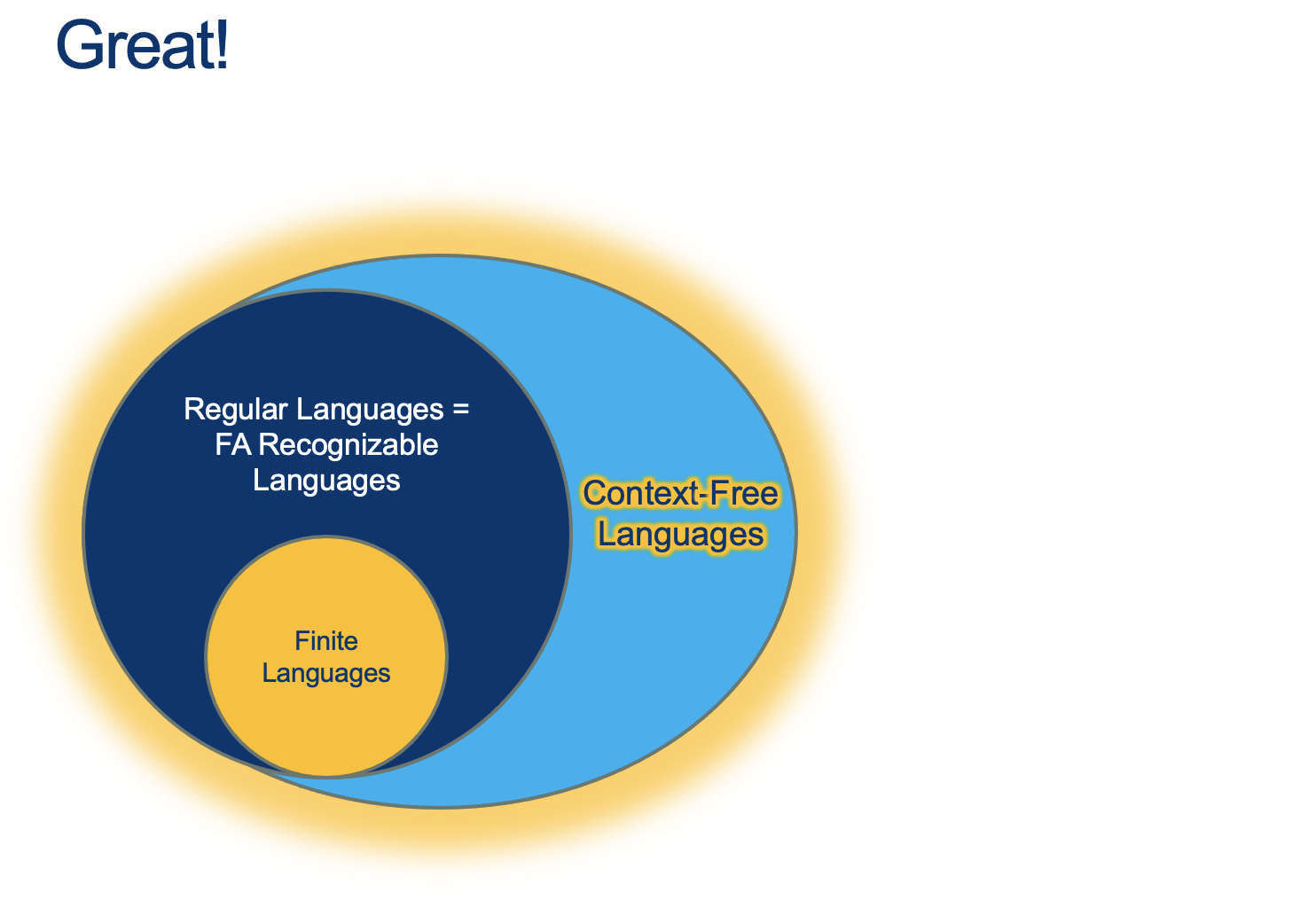

In the following map…

- Where are CFGs?

- How would we represent a finite language with a CFG?

- How would we represent a regular language with a CFG?

- Is there something outside a CFG?

- Where is EQ?

Ideas to prove all RL’s are “inside” CFGs

(You suggest some:)

Tip for designing Context-Free-Languages

Many CFLs are the union of simpler CFLs. If you must construct a CFG for a CFL that you can break into simpler pieces, do so and then construct individual grammars for each piece.

Example:

If the objective is to design a grammar for $ {0^n1^n \mid n>0 } \cup {1^n0^1 \mid n>0 }$, start with two sub-languages using sub-“starting symbols” and then join them to get the target language starting at $S$

You can build:

$S_1 = 0S1 \mid \epsilon $

and

$S_2 = 1S0 \mid \epsilon$, :

And then join them to obtain:

\[\begin{alignat}{2} S &= S_1 \mid S_2 \\ S_1 &= 0S_1 1 \mid \epsilon \\ S_2 &= 1S_2 0 \mid \epsilon \end{alignat}\]So now, how would we “Build” a Regular Language using a CFG?

Approach 2: RL’s are a special case of CFLs

You can convert any DFA into an equivalent CFG as follows.

- Make a variable $S_i$ for each state $q_i$ of the DFA.

- Add the rule $S_i$ → $aS_j$ to the CFG if $\delta (q_i,a) = q_j$ is a transition in the DFA.

- Add the rule $S_i$ → ε if qi is an accept state of the DFA.

- Make $S_0$ the start variable of the grammar, where $q_0$ is the start state of the machine.

Verify on your own that the resulting CFG generates the same language that the DFA recognizes.

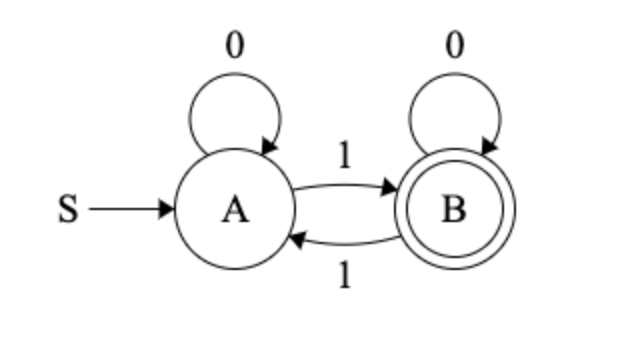

Activity 1 [2 minutes]:

Try to build your own CFG. One that “Accepts” the language: $ L = { w \in \Sigma^* \vert w \ has \ an \ odd \ number \ of \ 1s }$

(Wait; then Click)

if A is $S_0$ and B is $S_1$: $$ \begin{alignat}{2} S &\rightarrow_g S_0 \\ S_0 &\rightarrow_g 0S_0 \\ S_0 &\rightarrow_g 1S_1 \\ S_1 &\rightarrow_g \epsilon \\ S_1 &\rightarrow_g 0S_1 \\ S_1 &\rightarrow_g 1S_0 \\ \end{alignat} $$

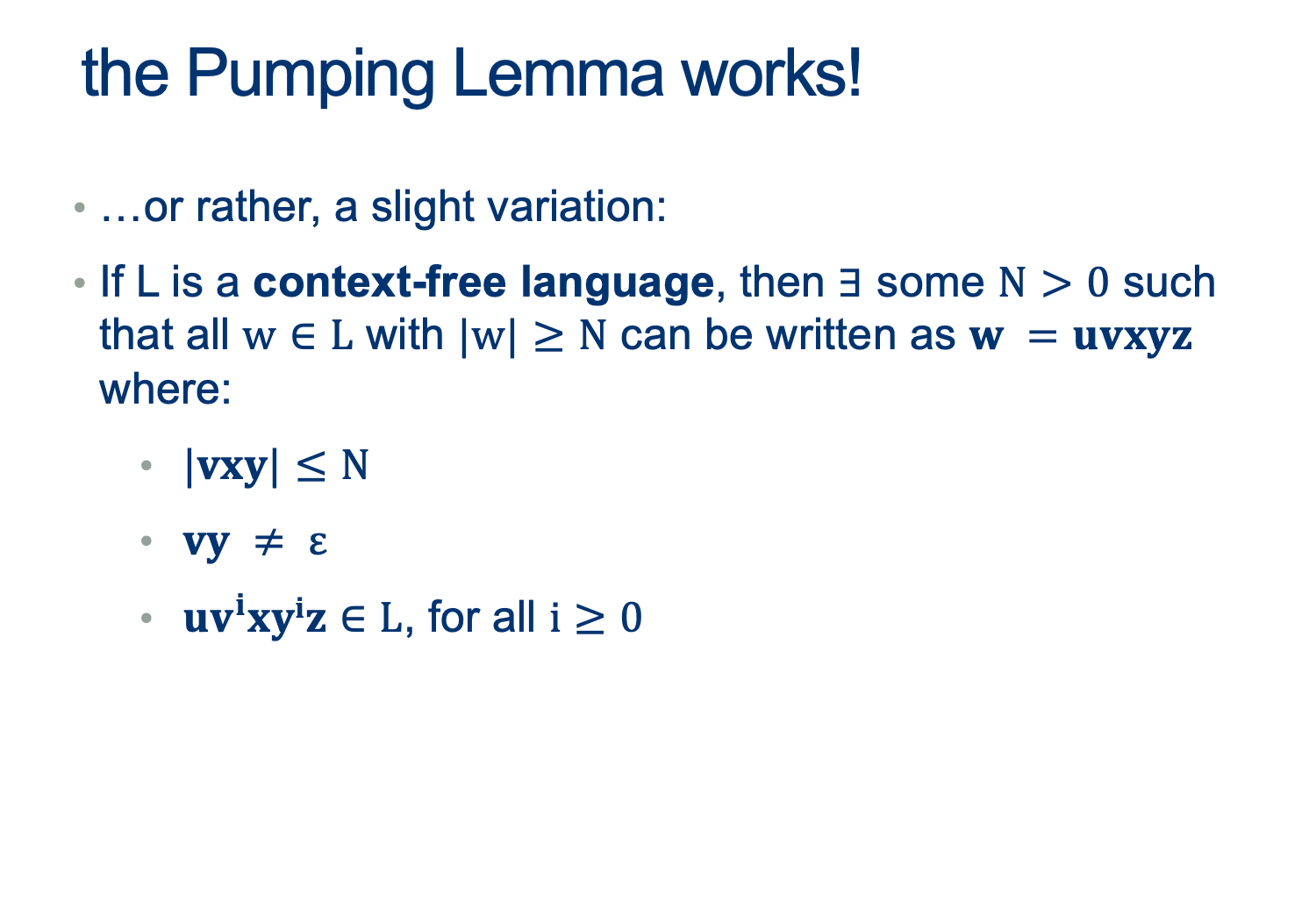

How do we prove there are languages that are NOT (beyond) CFLs?

How did we do this back when we did it for RLs?

- the middle part is not too big

- v and y (the repeating parts) are not both simultaneously empty

- repeating v and or y we will keep us in the language

Note that RLs are a special case of Context-Free-Languages (without the $uv^i$) part.

So, if we have a pumping lemma for CFGs, is there a “Machine” equivalent to the Finite Automatons as well?

We’ll see those next class.

Proving a language is NOT context-free

What does your intuition say? Is it a CFL?

Remember:

- Given a structure of $w = uvxyz$, and $ \mid vy \mid \geq 1$

- We want to find an $i$ for which a word $uv^ixy^iz$

does not have a prime length ( $ \mid uv^ixy^iz \mid $ is not prime ) after being “pumped” some number of times. - Here, we can start with a word $w$ with length $p\geq N $ ($N$ provided by the pumping Lemma)

- Now, the trick is to pump the pattern some number of times so that we can prove that the final length is NOT prime!

-

Ideas?

answer:(Wait; then Click)

Steps:

- The length of a word $\mid uv^ixy^iz \mid $ is the length of $ \mid w \mid $ plus any added repetitions of $v$ and $y$

- So, $ \mid uv^ixy^iz \mid $ is $ \mid w\mid + (i-1)\mid vy \mid $

- Since we said $w$ is in PRIMEAL, then $ \mid w\mid $ is some prime number $p\geq N $.

- Then, $ \mid uv^ixy^iz \mid = \mid w\mid + (i-1)\mid vy \mid = p + (i-1)\mid vy \mid$

- Now, What possible choice of $i$ could we choose to cause the overall length to be provably NOT prime ?

Answer Below:

(Wait; then Click)

If we choose $i$ so that the $i-1$ is equal to $p$ in the following expression: $$ \mid uv^ixy^iz \mid = \mid w\mid + (i-1)\mid vy \mid = p + (i-1)\mid vy \mid $$ Then substituting $i-1$ for $p$ ( by making $i = p-1$), we would get: $$ \mid uv^ixy^iz \mid = \mid w \mid + (i-1)\mid vy \mid = p + p\mid vy \mid \\ = p (1+\mid vy \mid) $$ which means that, after pumping, the word is divisible by $p$! and therefore, not of prime length.

Why are CFGs important?

check the article out: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature04675

Some Perspective

Why am I asking you all of these questions about regularity of languages, etc.?

REs and FAs are really simple computational machines.

What does this have to do with getting your Java code to compile, or using dynamic programming, or …

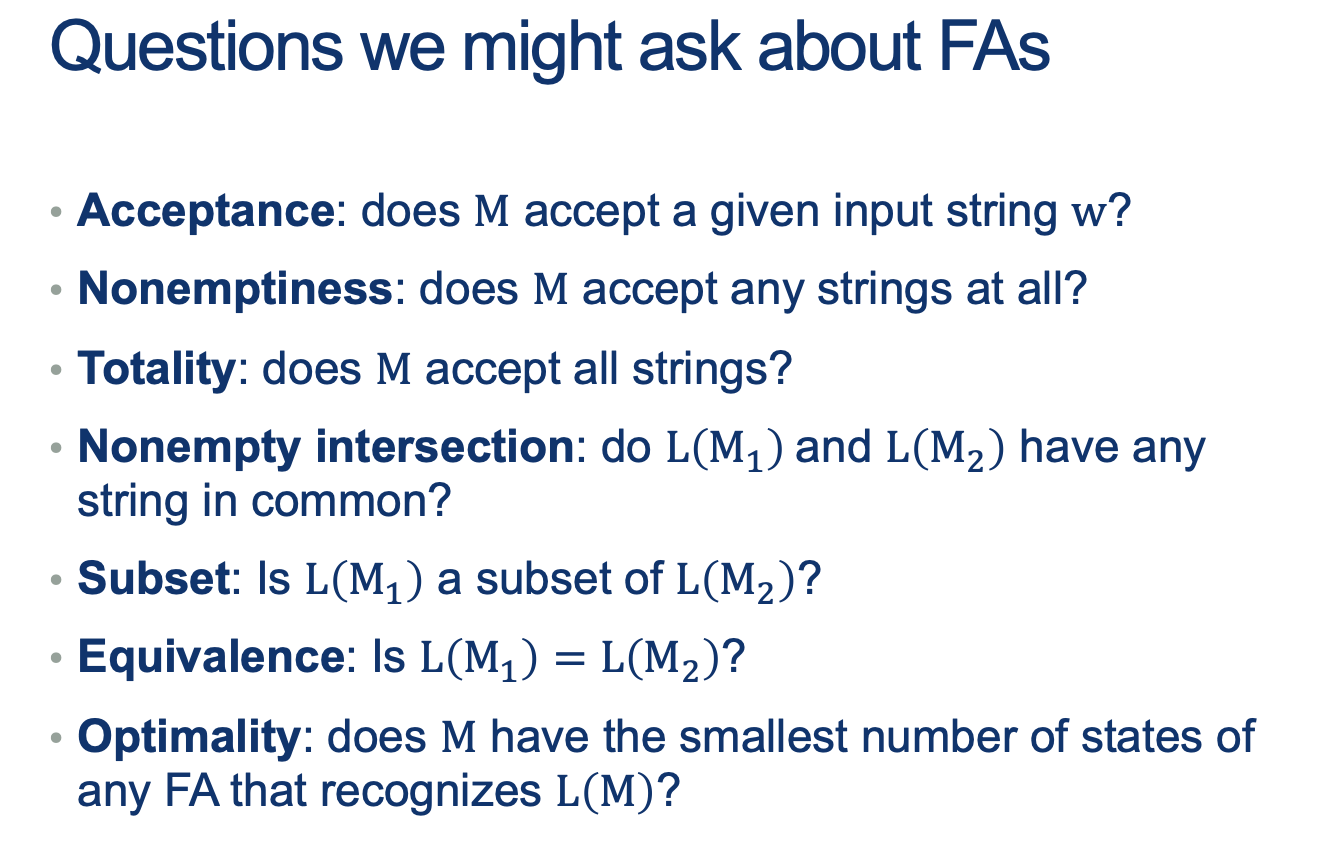

Turns out that there are some surprisingly algorithmic things we can do when we start asking questions about these simple machines.

Let’s take a look at some questions we might ask.

Why are RegExes or FAs useful?

Think about these problems:

- You have written a long essay and you realize that you misspelled a name in all of it! The name Theodore should be replaced for the name Teodoro: How do you tell a program to find all the words tnhat should be changed!

- You want to design a deck-building card game where players accumulate cards and can gain points by making groups of cards and playing them. How do you define the rules for the game and print out all the combinations that are allowed or check if a combination is allowed?

- In terms of programming, you can use regular expressions to indicate password-rule matching, smart character replacement, email format checkers, etc. –>