Lecture Notes 14: Intro to Turing Machines

Outline

This class we’ll discuss:

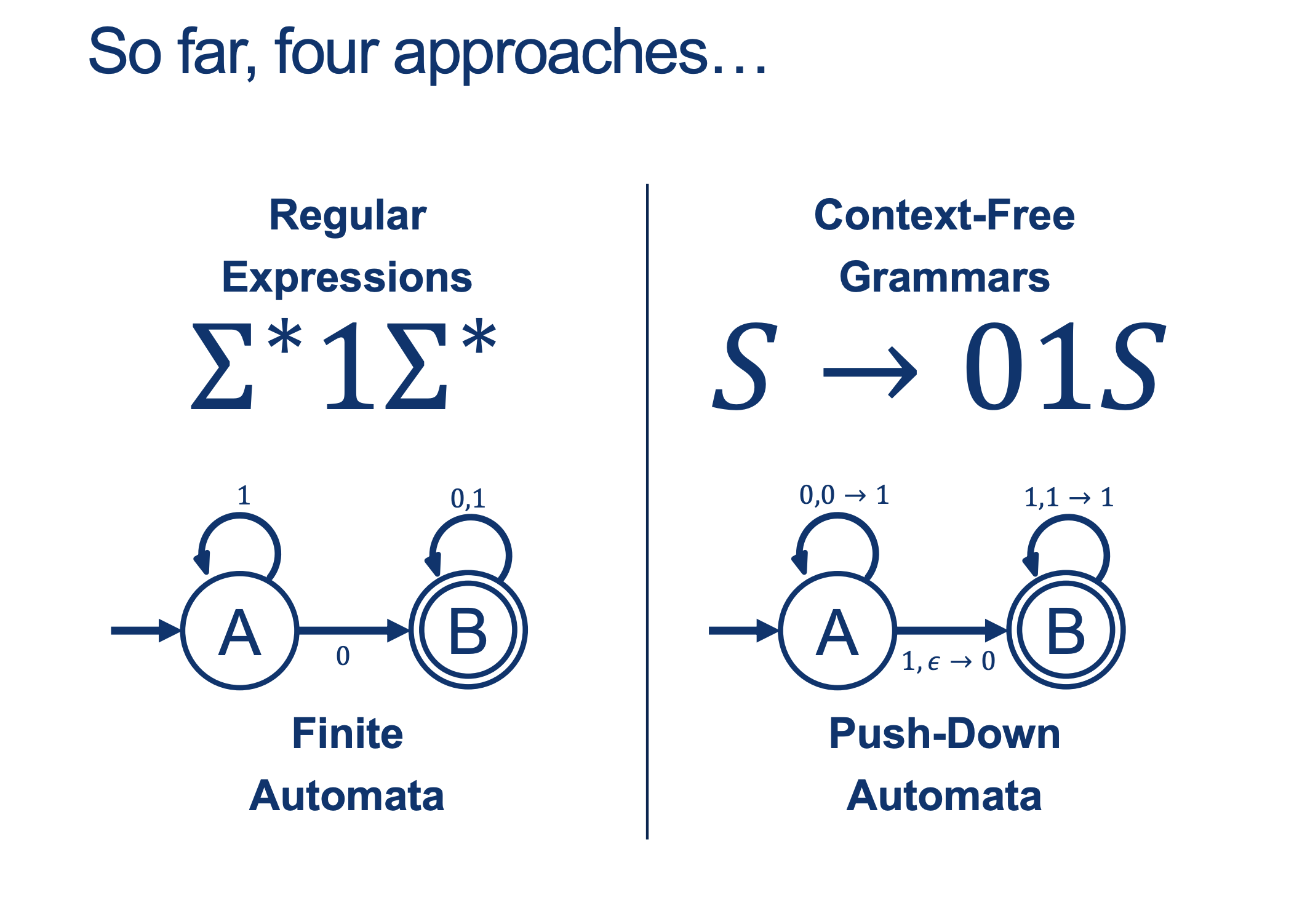

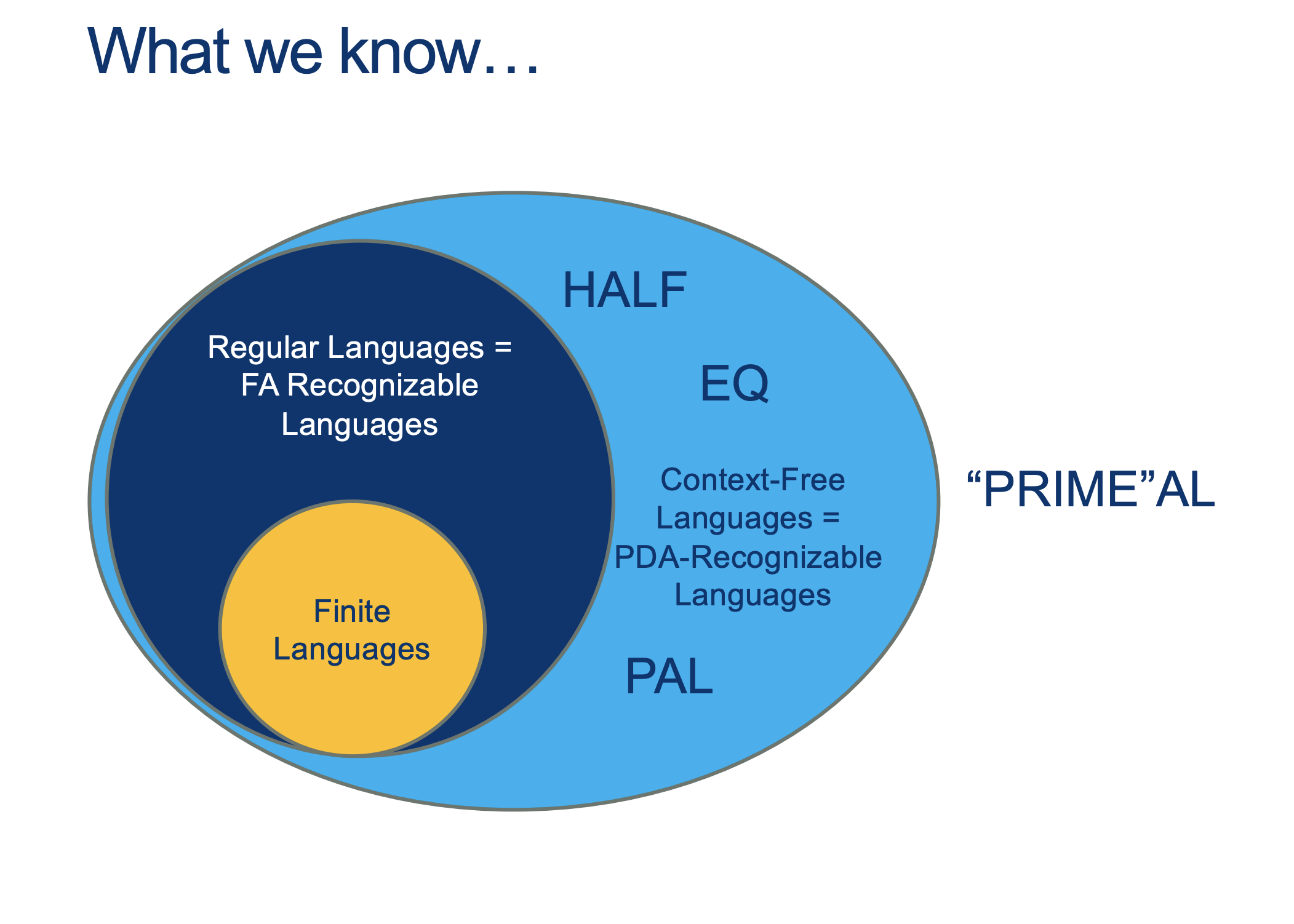

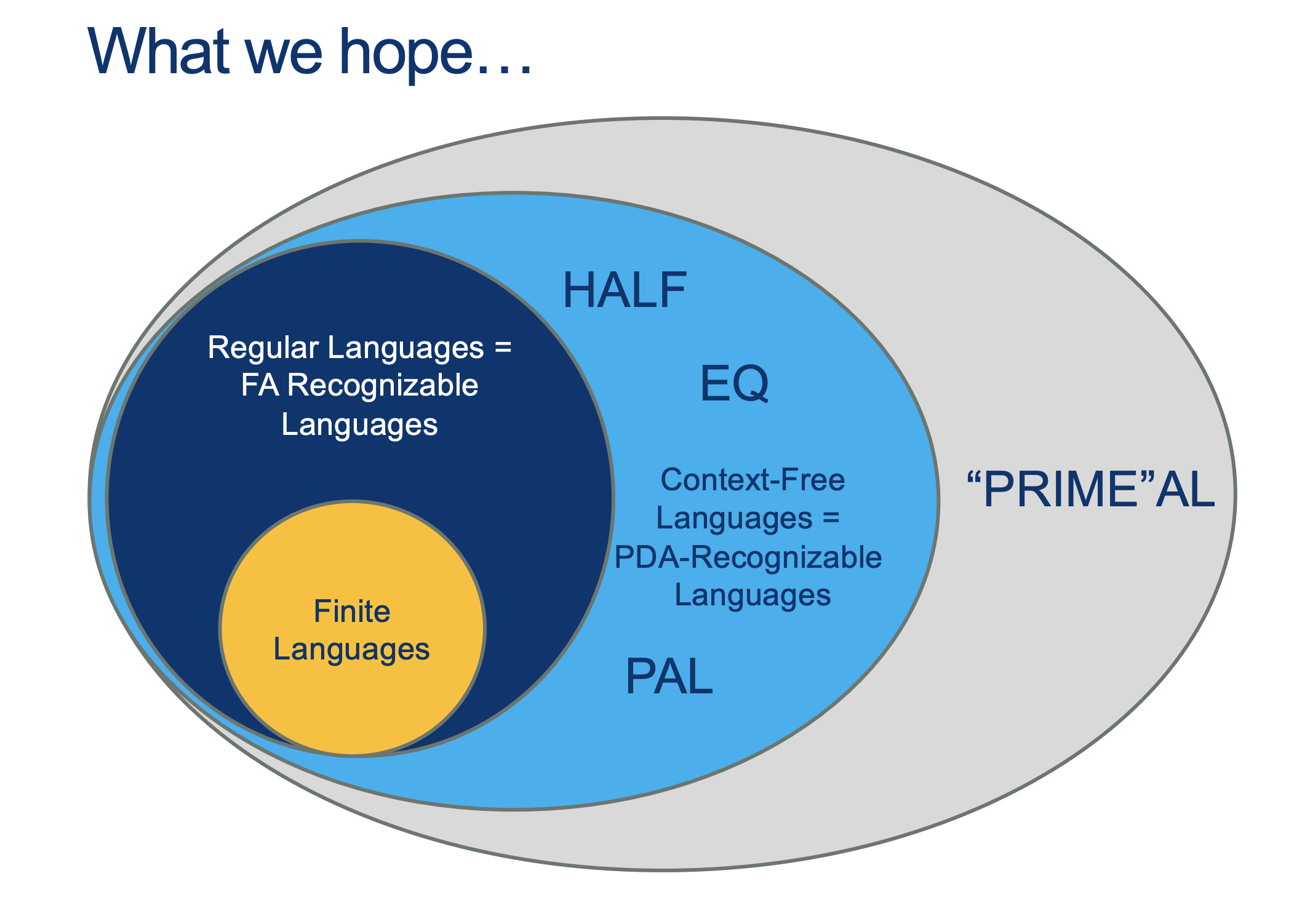

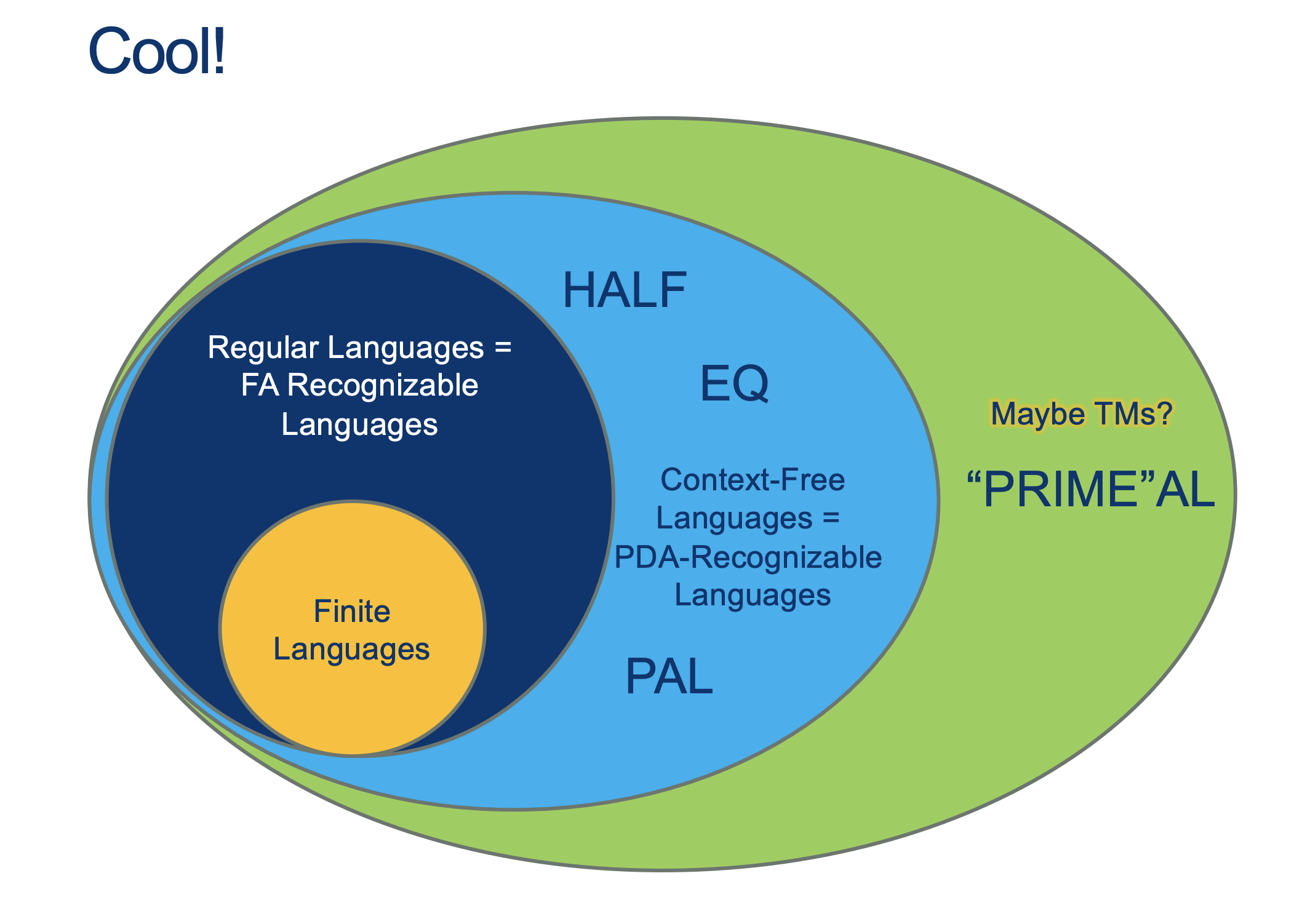

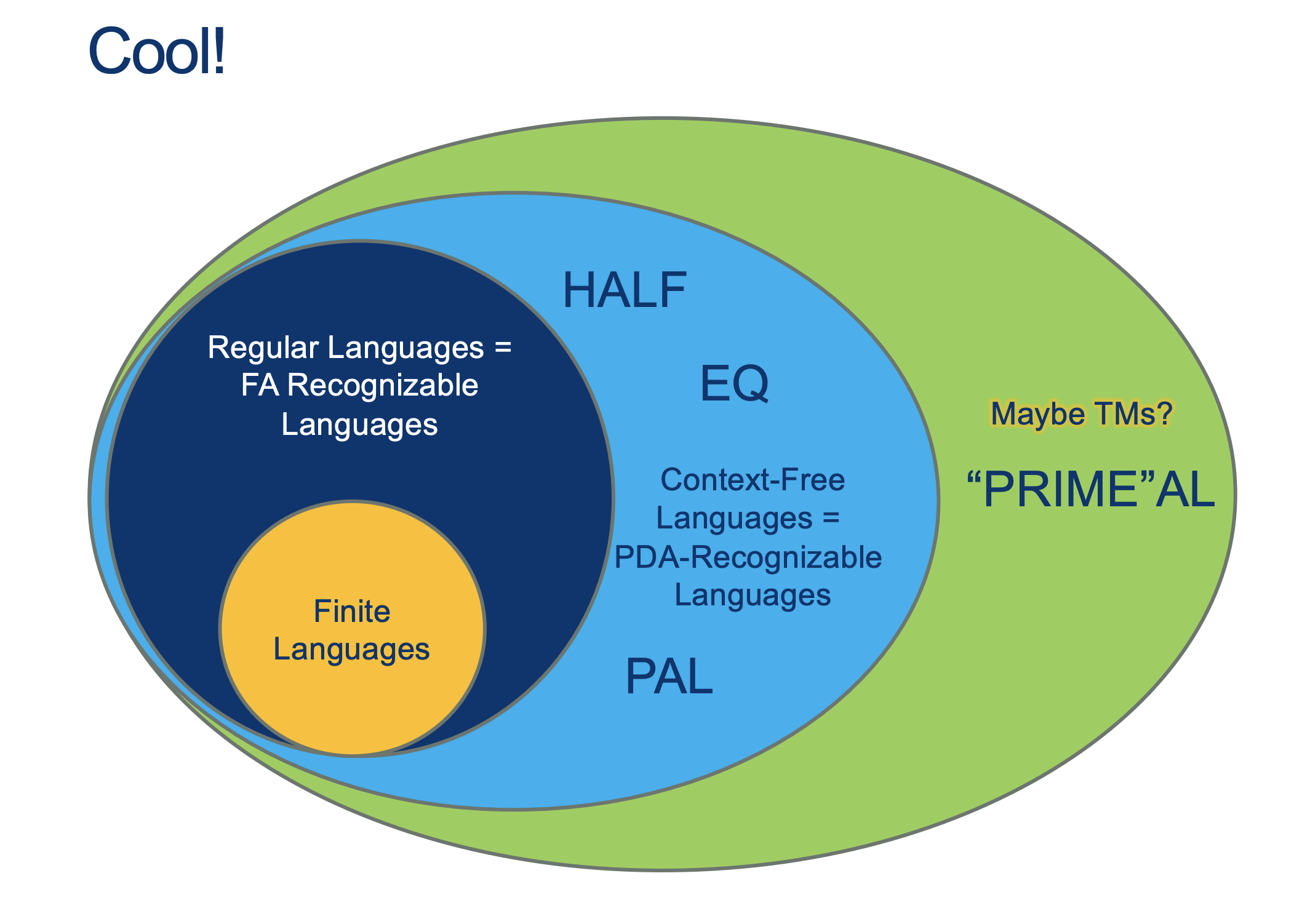

- Recap: REs and CFGs

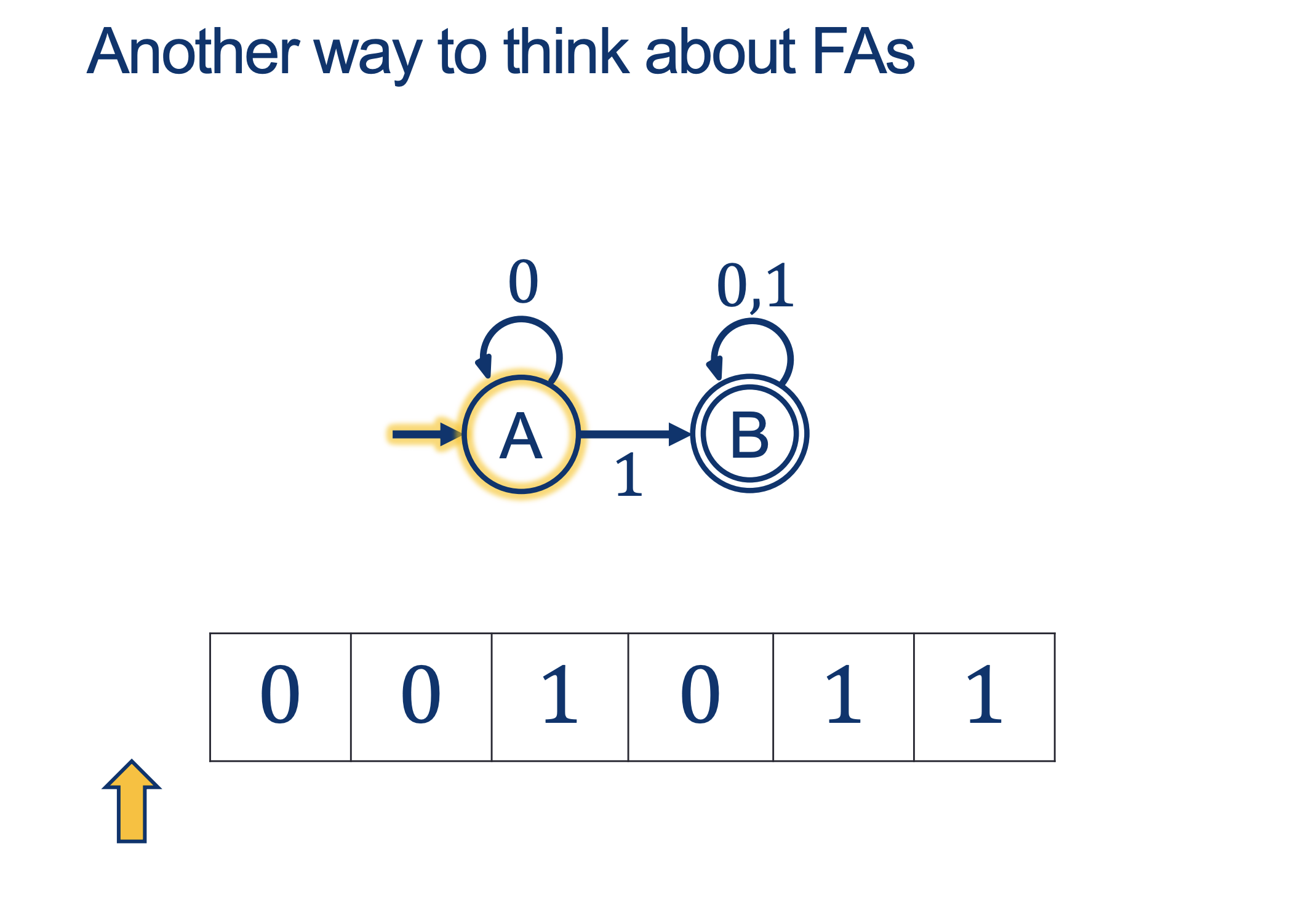

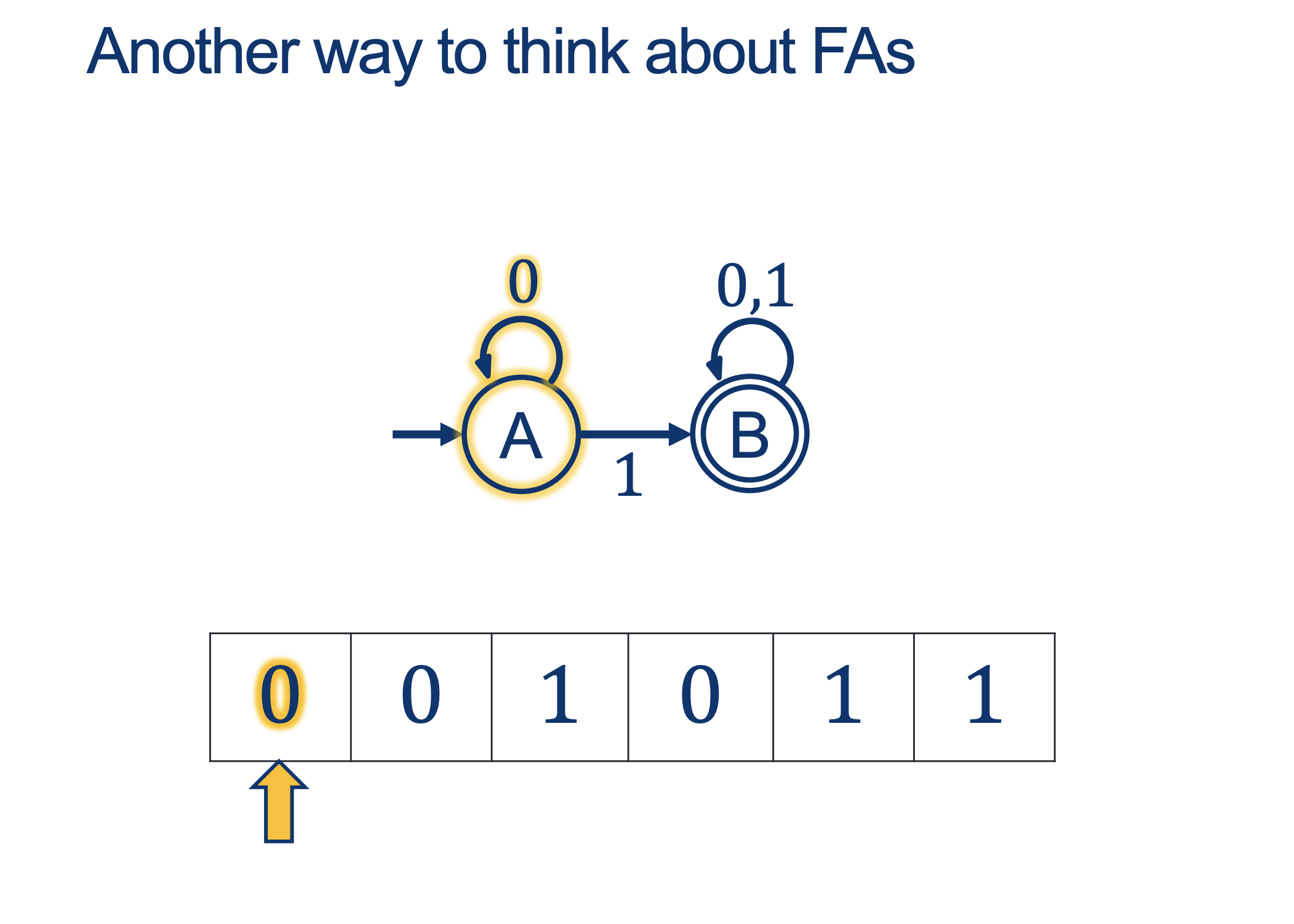

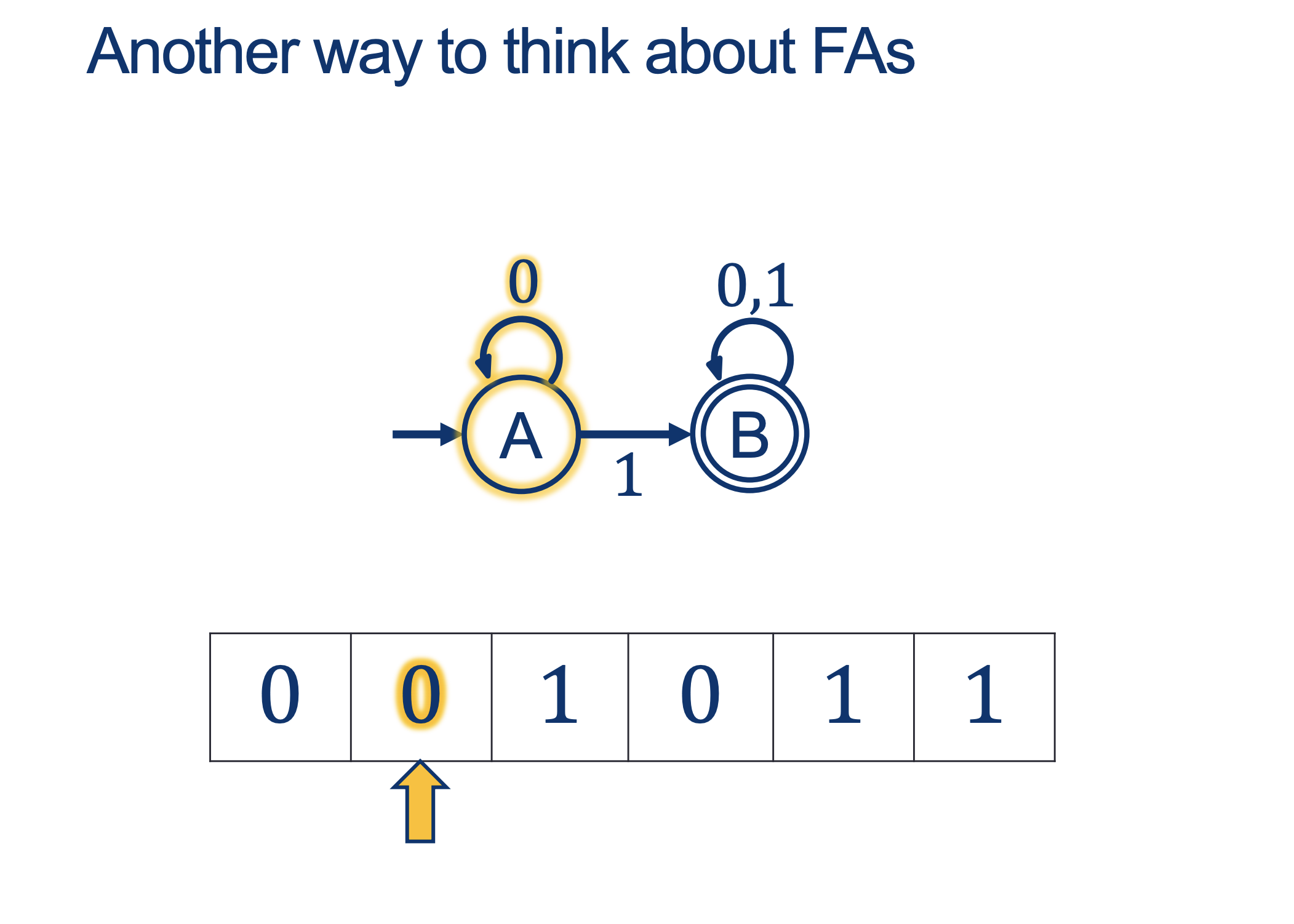

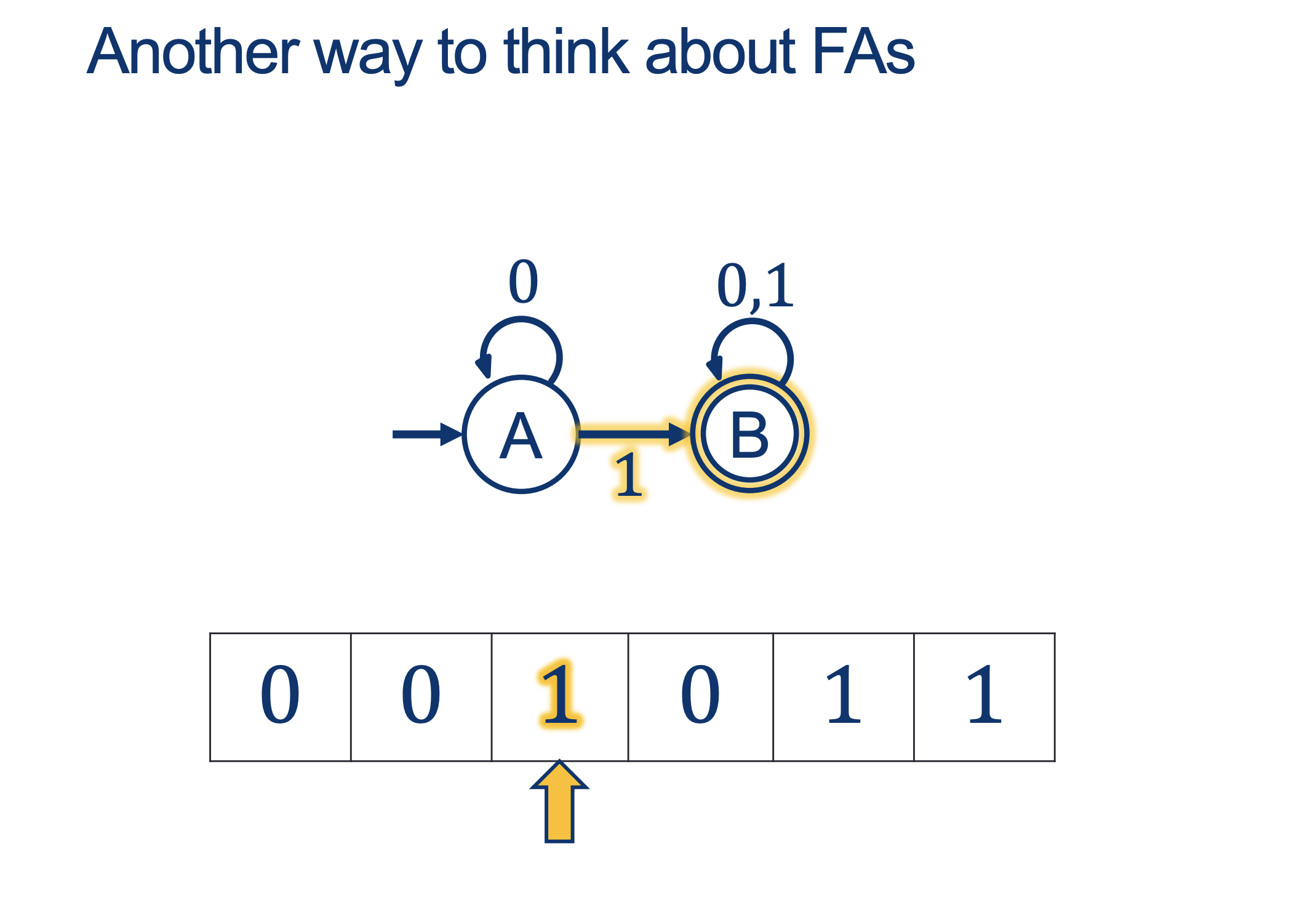

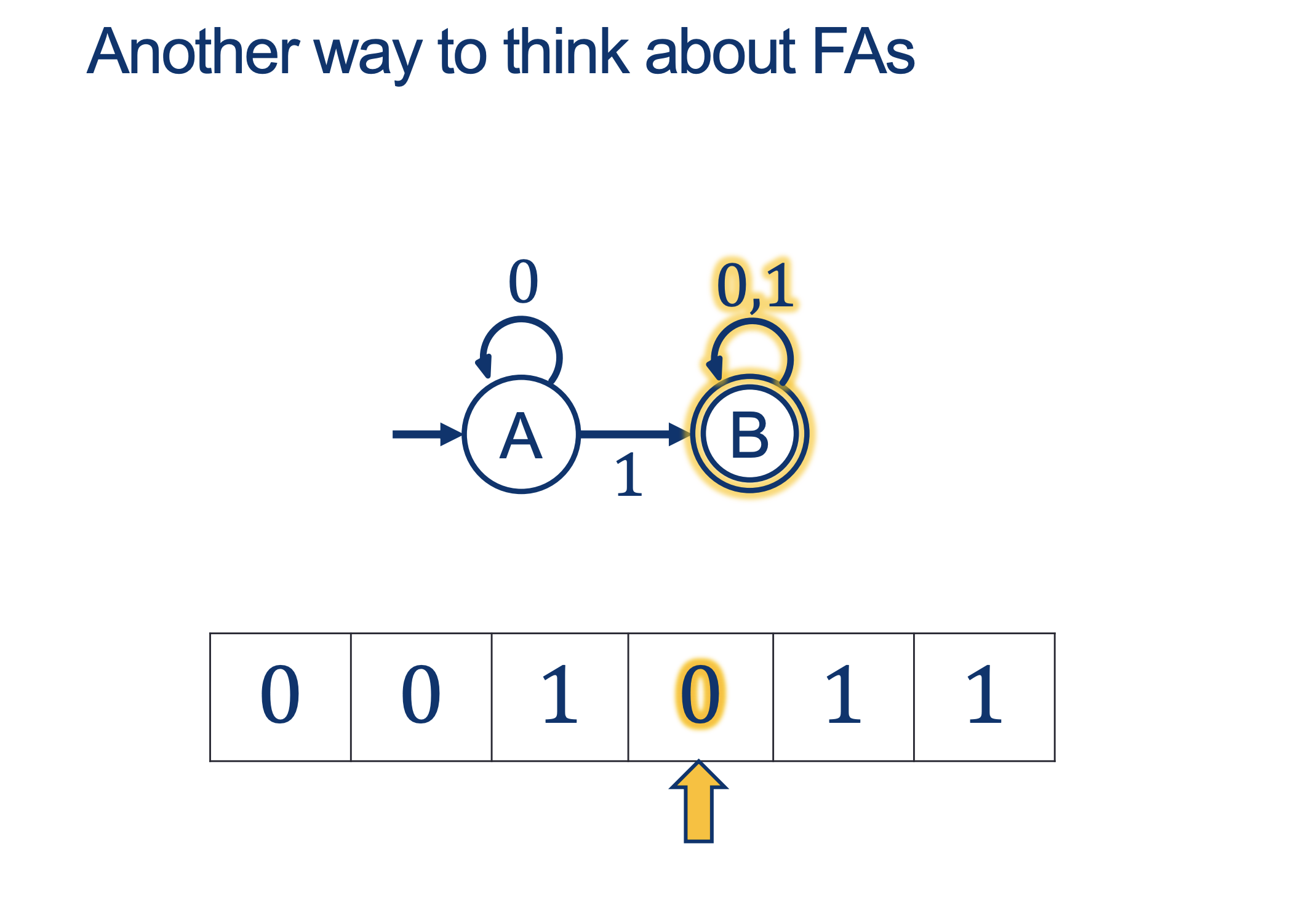

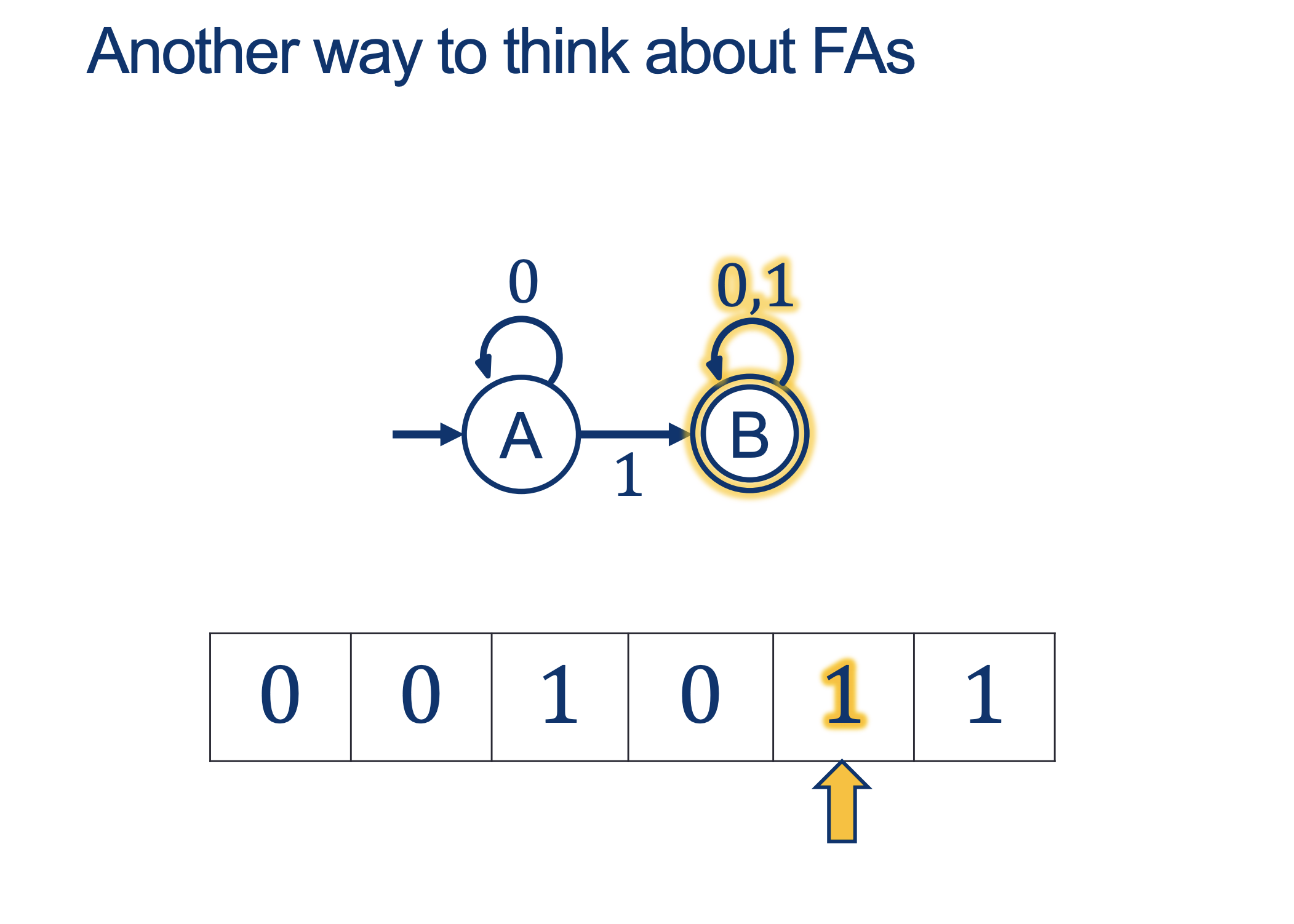

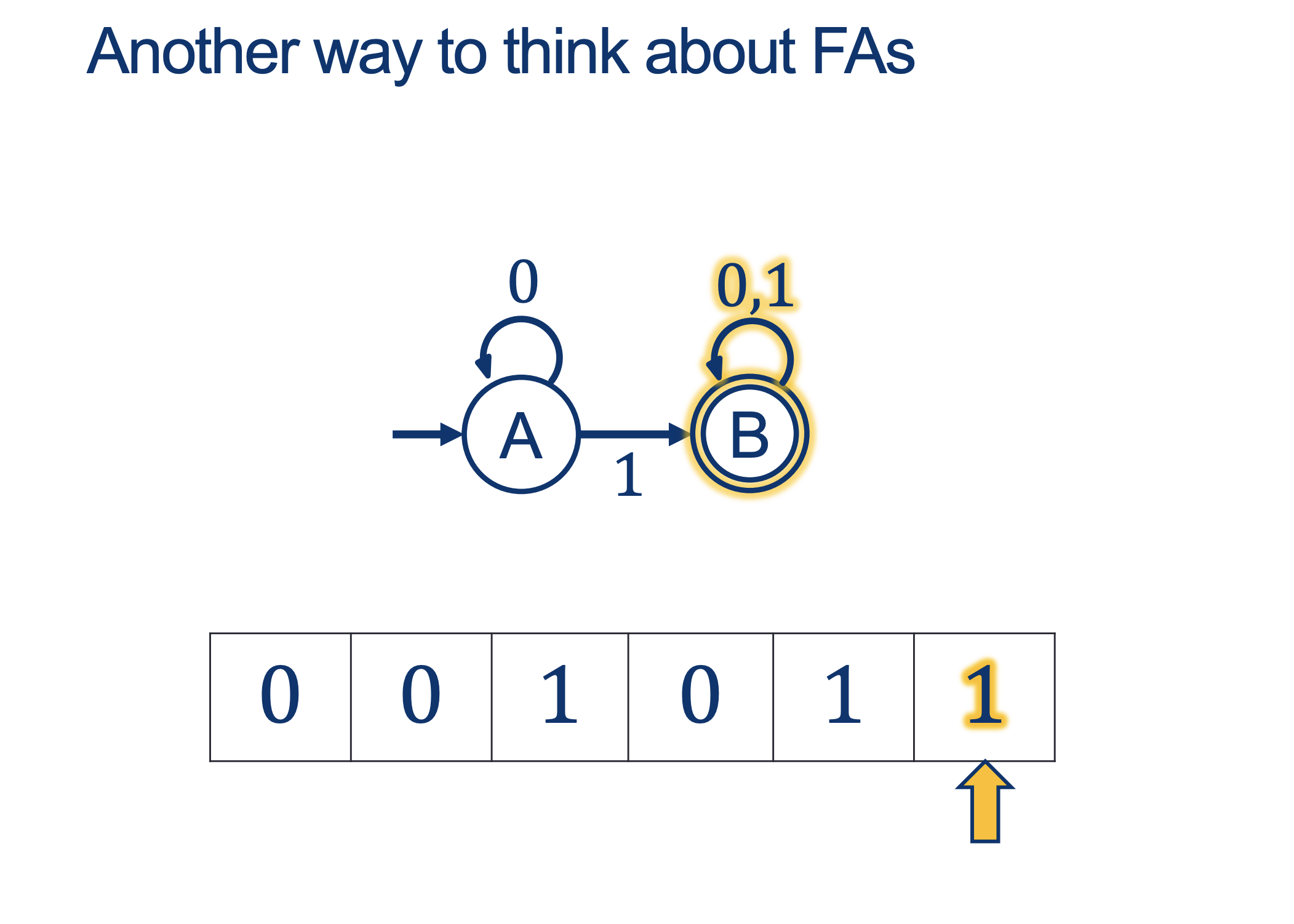

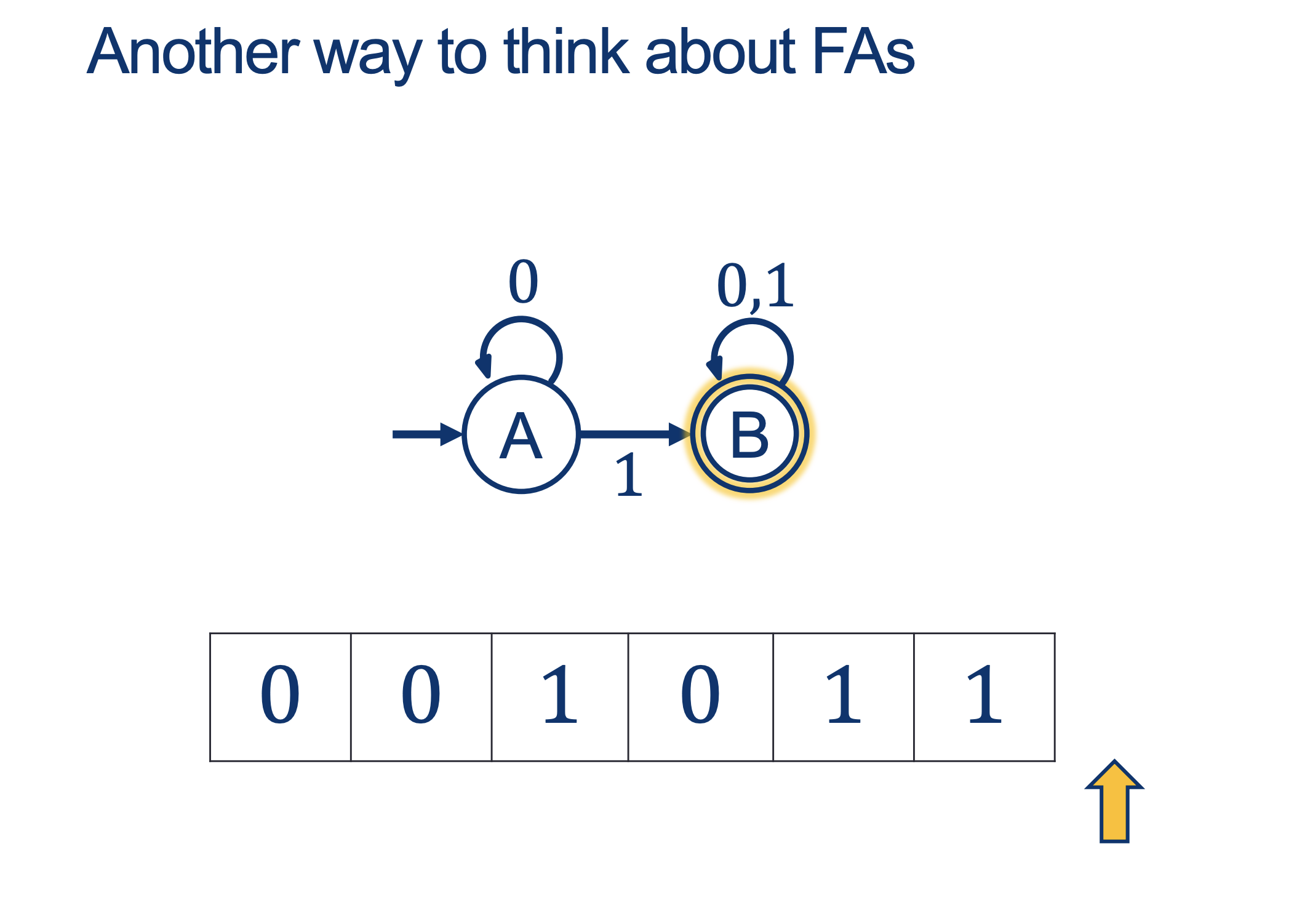

- The “tape-processing” view

- More powers: TMs

A Slideshow:

GUIDED NOTES (Optional)

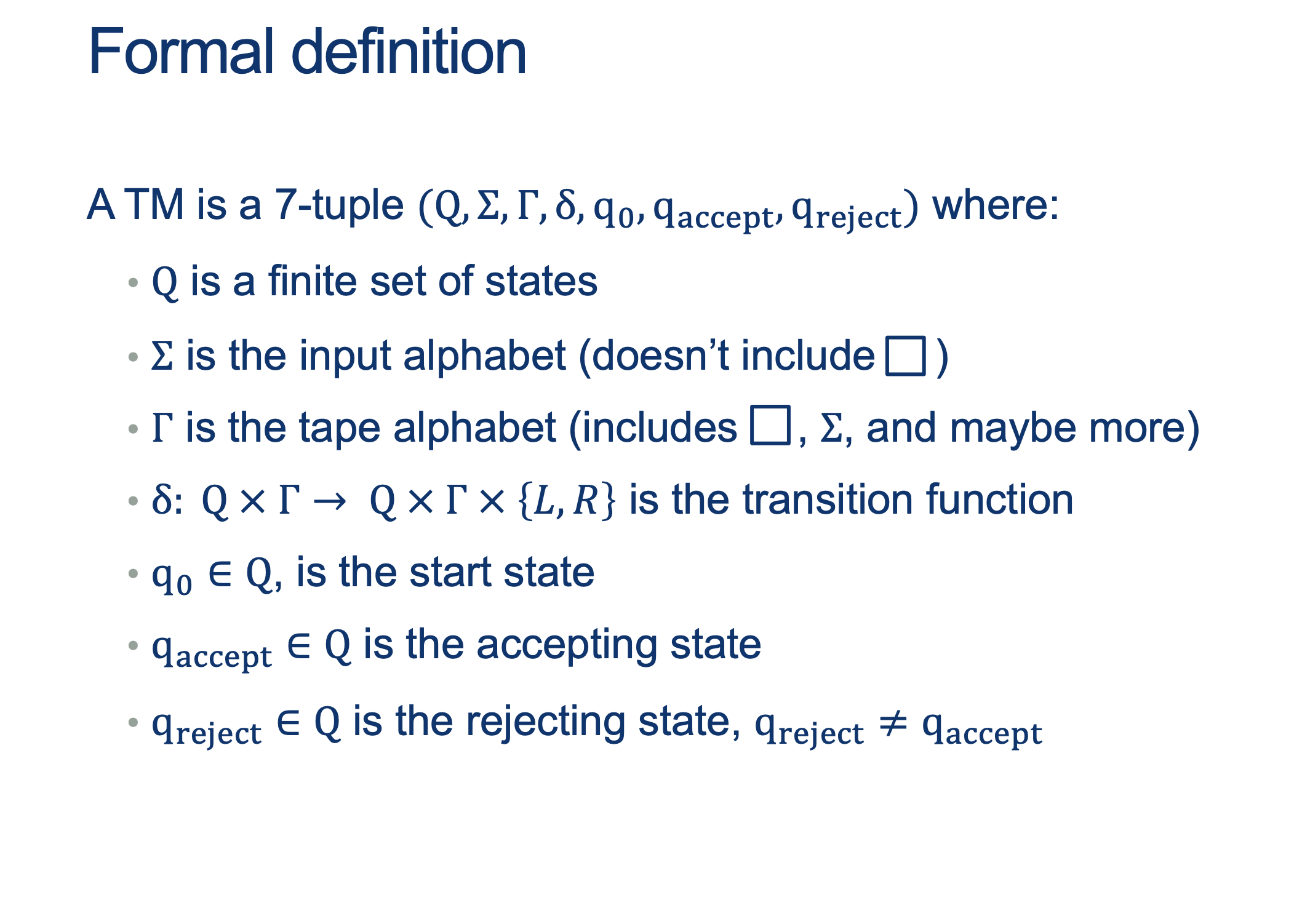

Turing Machines

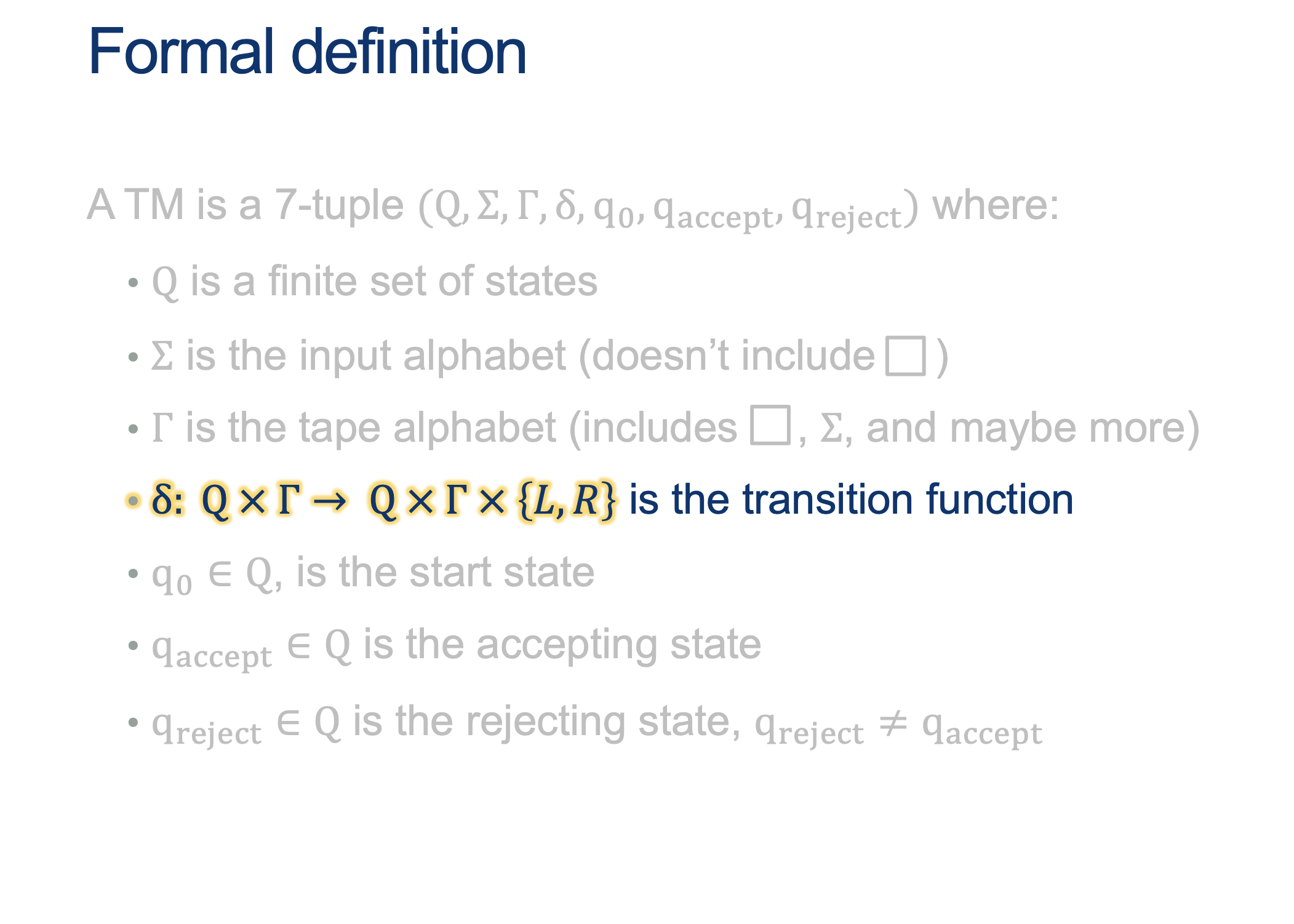

So, a transition would look like this:

\[(r, w, m)\]where each of the elements means:

- r: what is Read from the “tape”

- w: what is Written into the “tape”

- m: the movement direction in the “tape”

Examples:

- (0, $\square$, L): IF we read a 0, we write a “blank” and move Left

- (1, 1, R): IF we read a 1, we write a 1 and move Right

- (0, 0, L): IF we read a 0, we write a 0 and move Left

(Wait; then Click)

Solution

Where would the reject state be?

But… we don’t need to write them like that!

Writing Turing Machines

These machines are so powerful, we can actually describe them with pseudocode.

Example, the machine shown above can also be described like this:

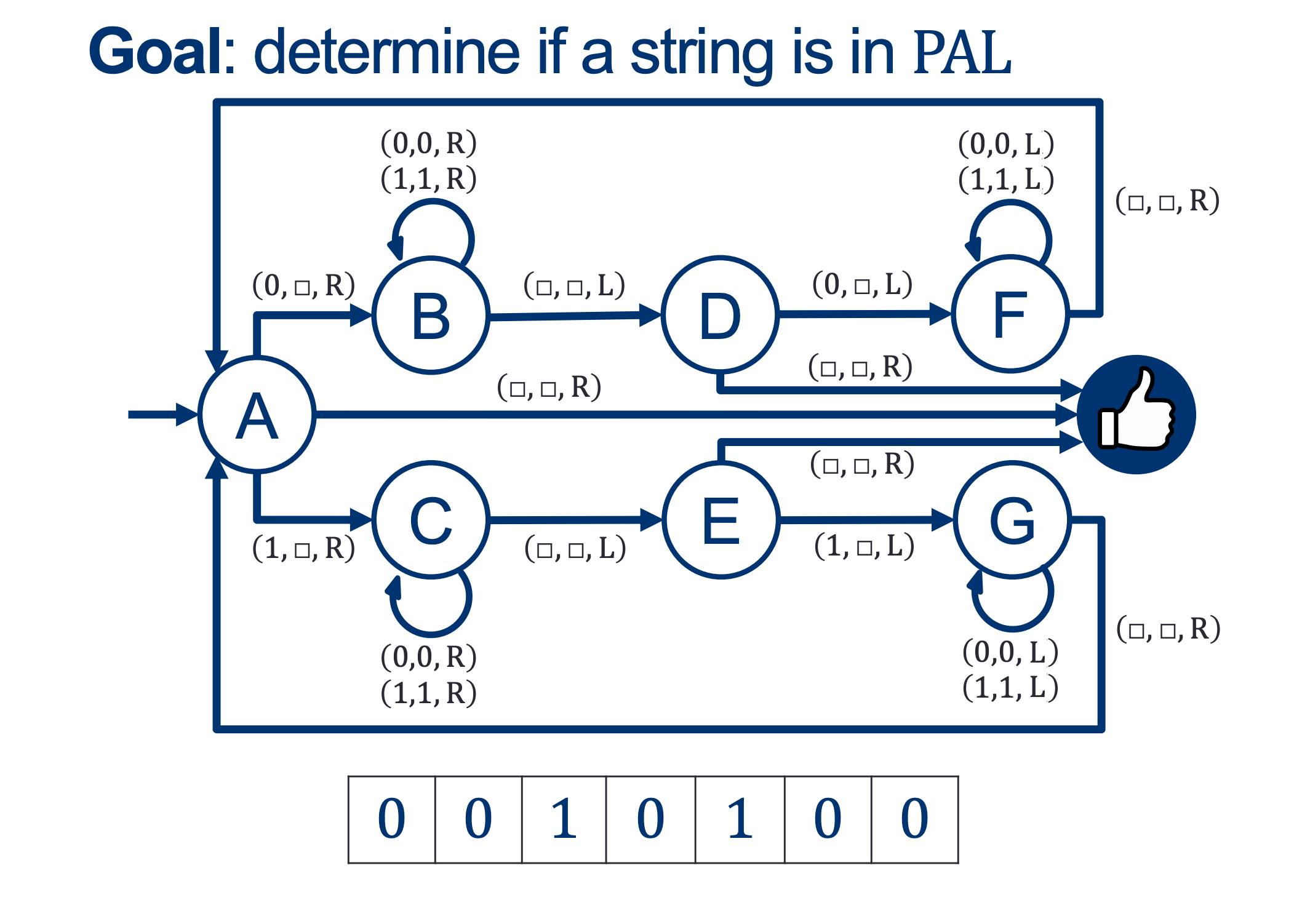

On input w:

while there are symbols left in the tape:

i. note whether 1st letter is a 0 or a 1 and erase it

ii. go all the way to the last symbol

iii. if this symbol doesn't match the one we just erased, REJECT;

otherwise erase it and go back to the start.

ACCEPT.

TM Powers

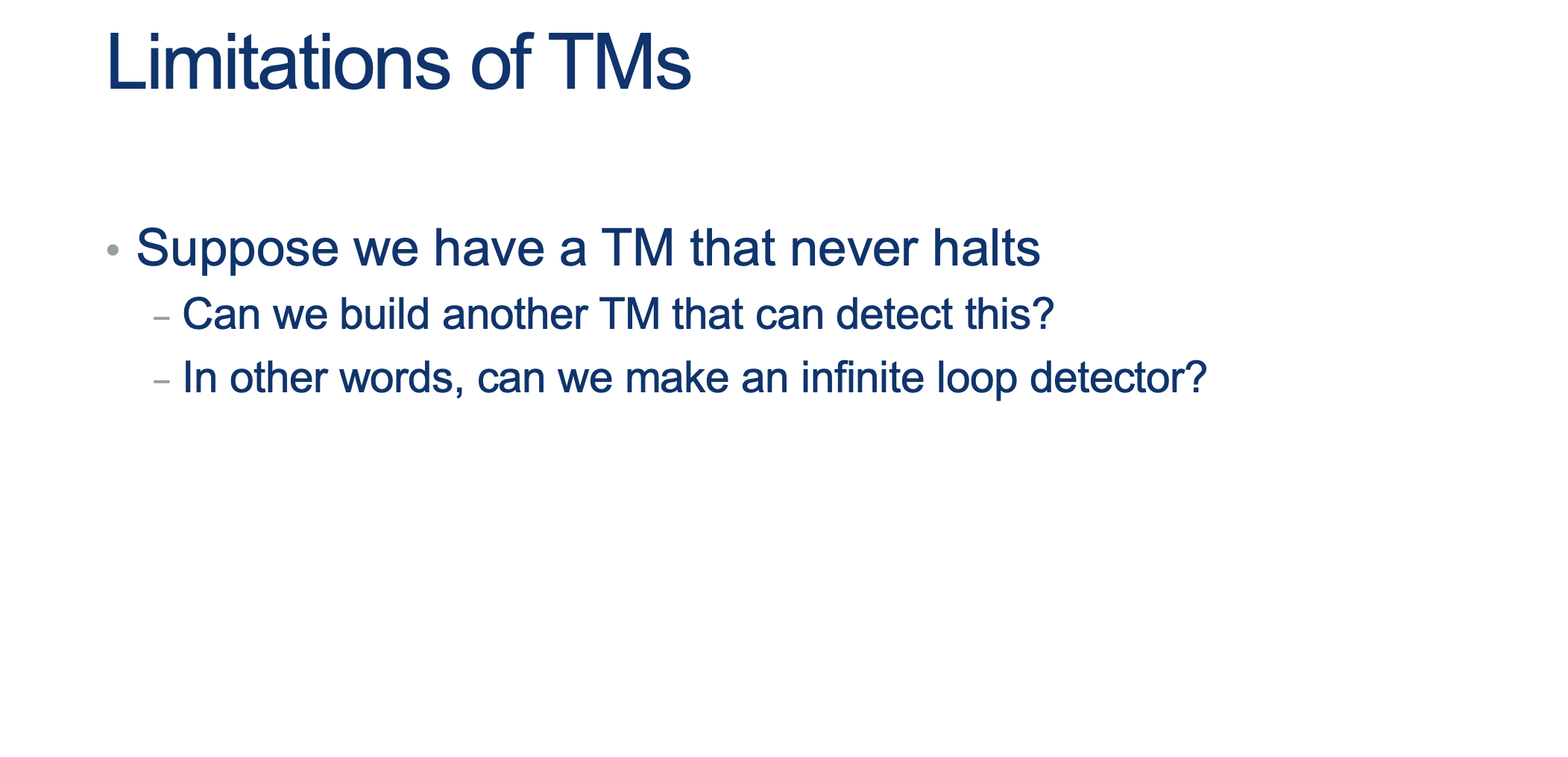

The magic Halting predictor machine H

Can we create a machine/routine (let’s call it machine H) that can predict if a program will halt?

Let’s watch the following video to see what could go wrong with such a machine H:

Halting Problem Video

Proof Sketch

The following is a (sketch of a) proof by contradiction:

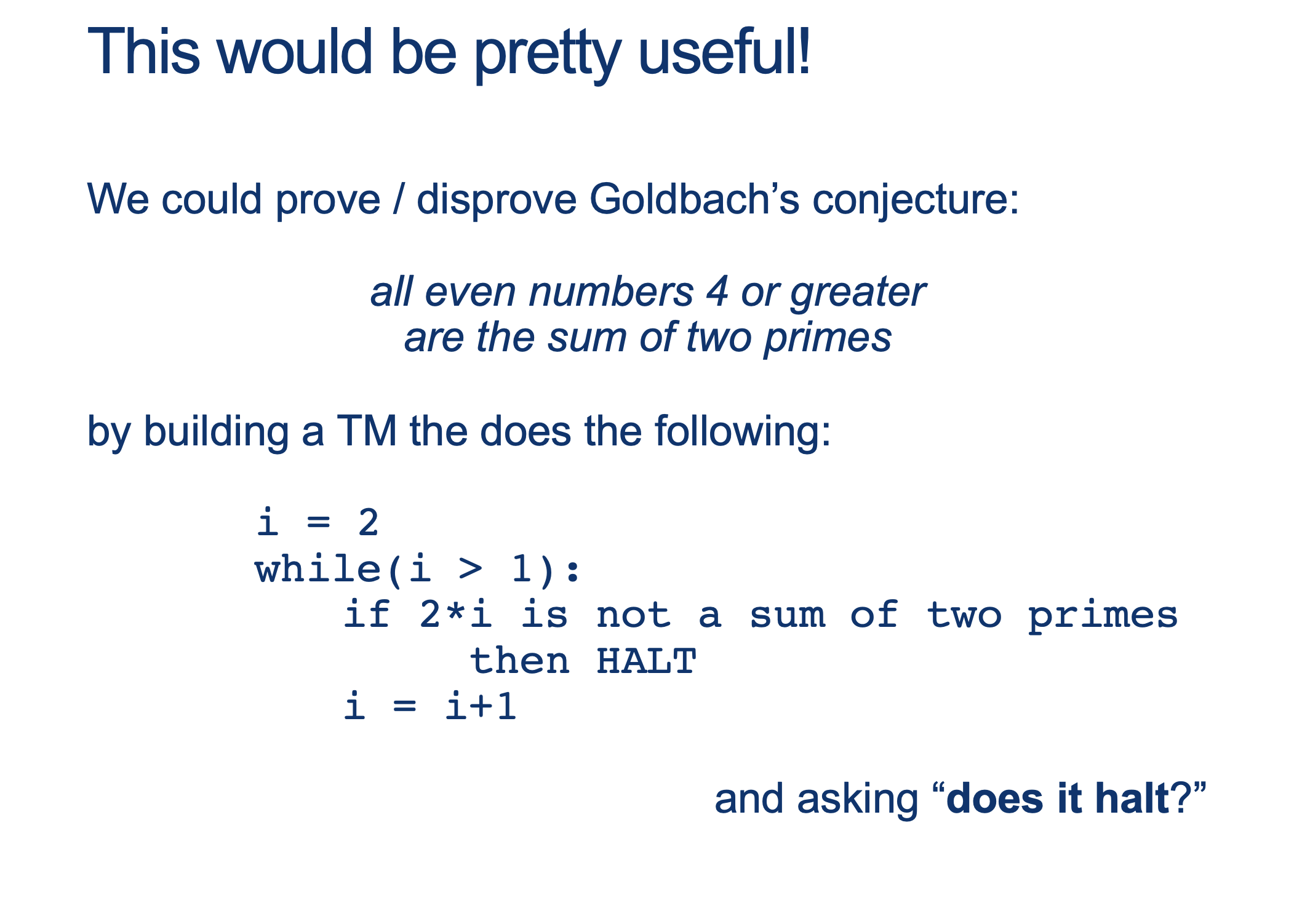

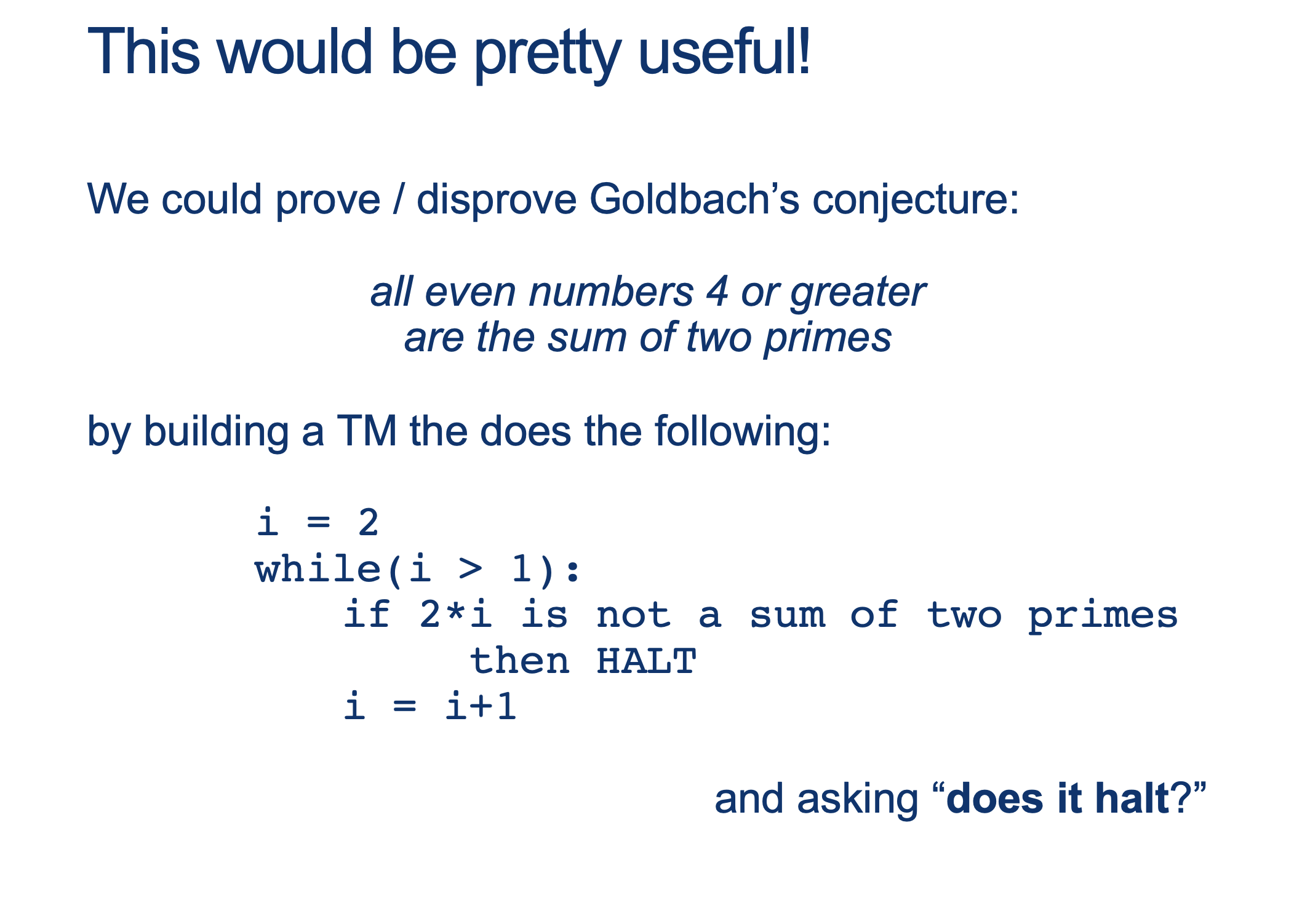

1: Say there exists a function called halts

halts(f) returns true if the subroutine f halts and returns false otherwise.

2: Now consider the following subroutine g:

What is happening here?

(Wait; then Click)

- halts(g) must either return true or false.

- If halts(g) returns true, then g will call loop_forever and never halt, which is a contradiction.

- Therefore, the initial assumption that halts is a total computable function must be false.

More on Turing Machines

Outline

This class we’ll discuss:

- Recap: Turing Machines

- Universal Turing Machines

- A Strange Turing Machine

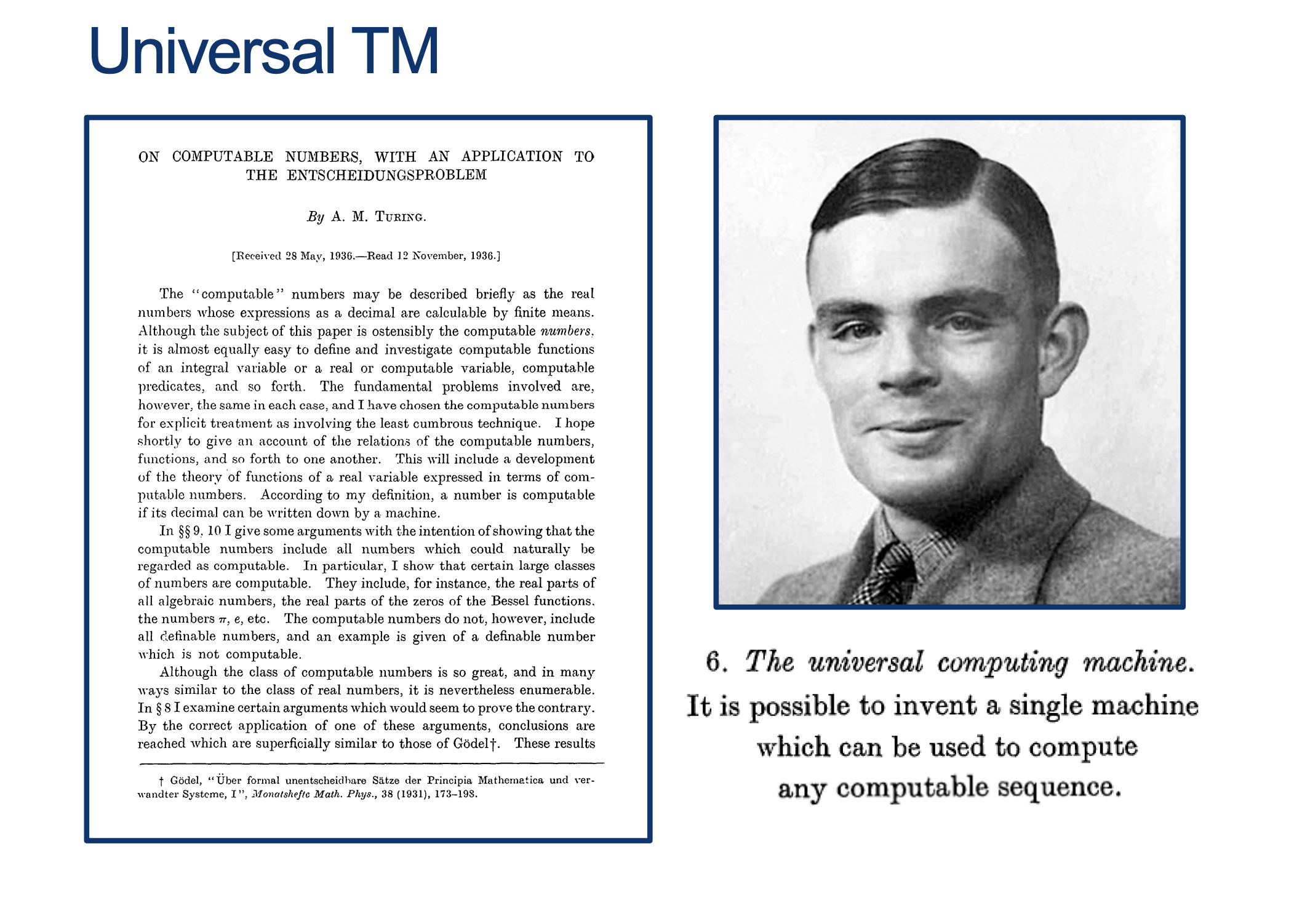

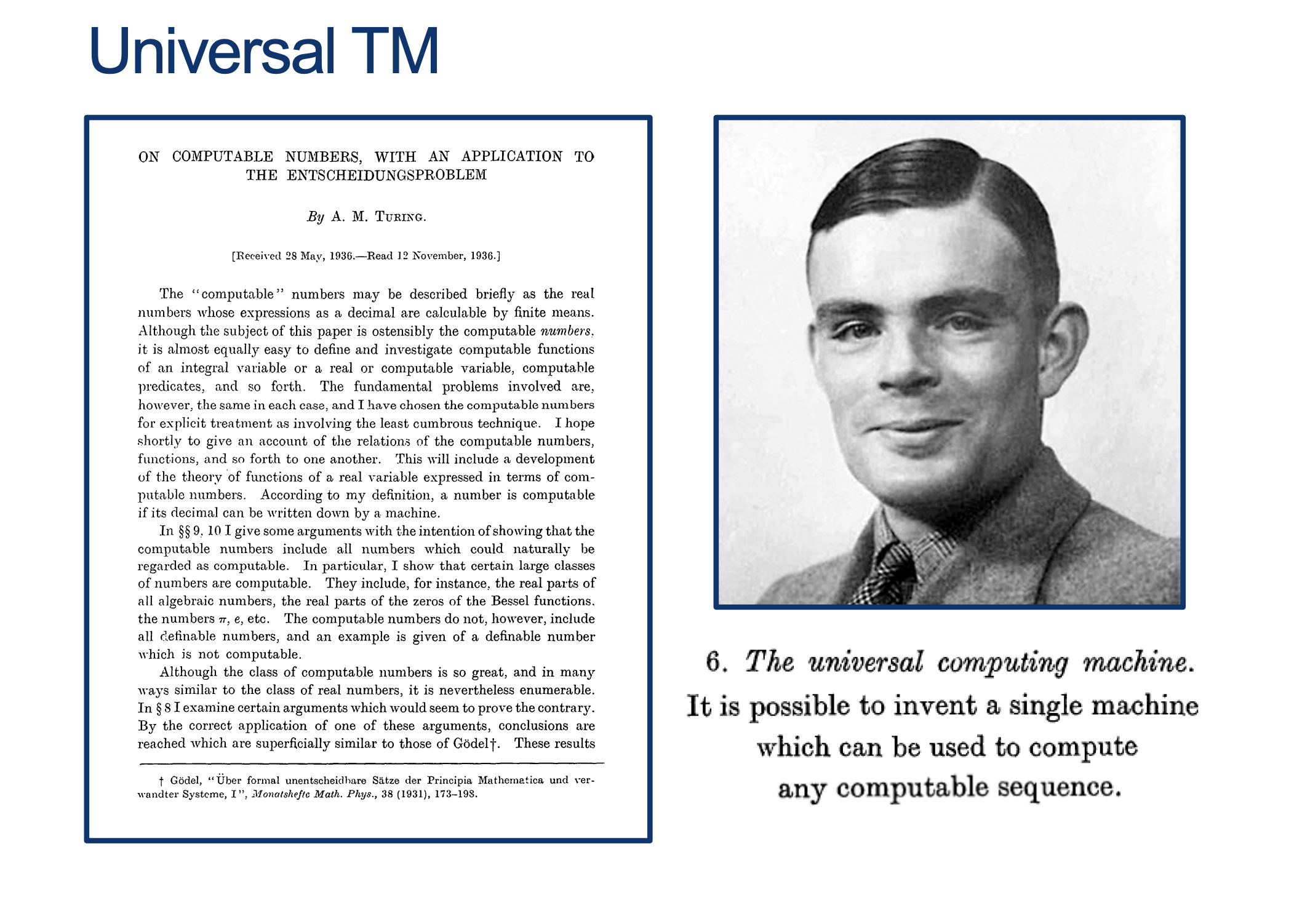

The Universal Turing Machine

The magic Halting predictor machine H

Can we create a machine/routine (let’s call it machine H) that can predict if a program will halt?

Let’s watch the following video to see what could go wrong with such a machine H:

Halting Problem Video

Proof Sketch

The following is a (sketch of a) proof by contradiction:

1: Say there exists a function called halts

halts(f) returns true if the subroutine f halts and returns false otherwise.

2: Now consider the following subroutine g:

What is happening here?

(Wait; then Click)

- halts(g) must either return true or false.

- If halts(g) returns true, then g will call loop_forever and never halt, which is a contradiction.

- Therefore, the initial assumption that halts is a total computable function must be false.

Here is another view of the haltin machine problem:

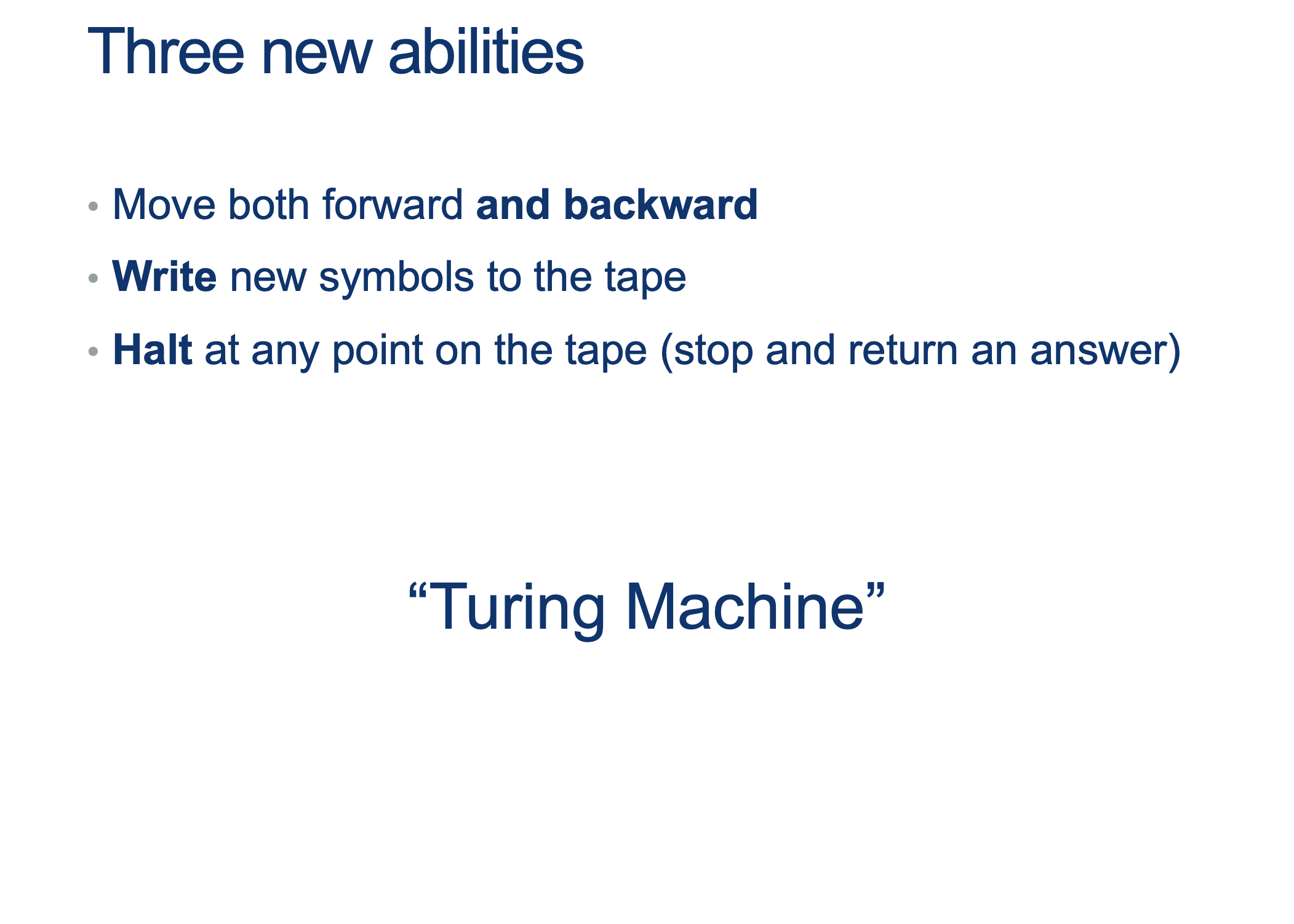

Turing Machines and Intro to Decidability

(Wait; then Click)

- move both left and right.

- write new symbols to the tape.

- stop at any point and return an answer.

Recognizing vs Deciding

Recognizing a word is having the capacity of saying “YES, I know this one”, if that word is in the Language $L$ you are able to “Recognize”.

Note: If you are trying to Recognize a word, but you are not done checking, …. how long do you wait?

In other words, you just say: If I say “YES”, I’m sure it is “YES” (ACCEPT), but I don’t promise anything else.

Deciding a word is having the capacity of saying “YES, I know this one”, if that word is in the Language $L$ you are able to “Decide”, AND “NO, this one is NOT one of mine” for ALL words that are not in the Language you are able to “Decide” (called the complement of $L$, or $L^c$ or $\bar{L}$.

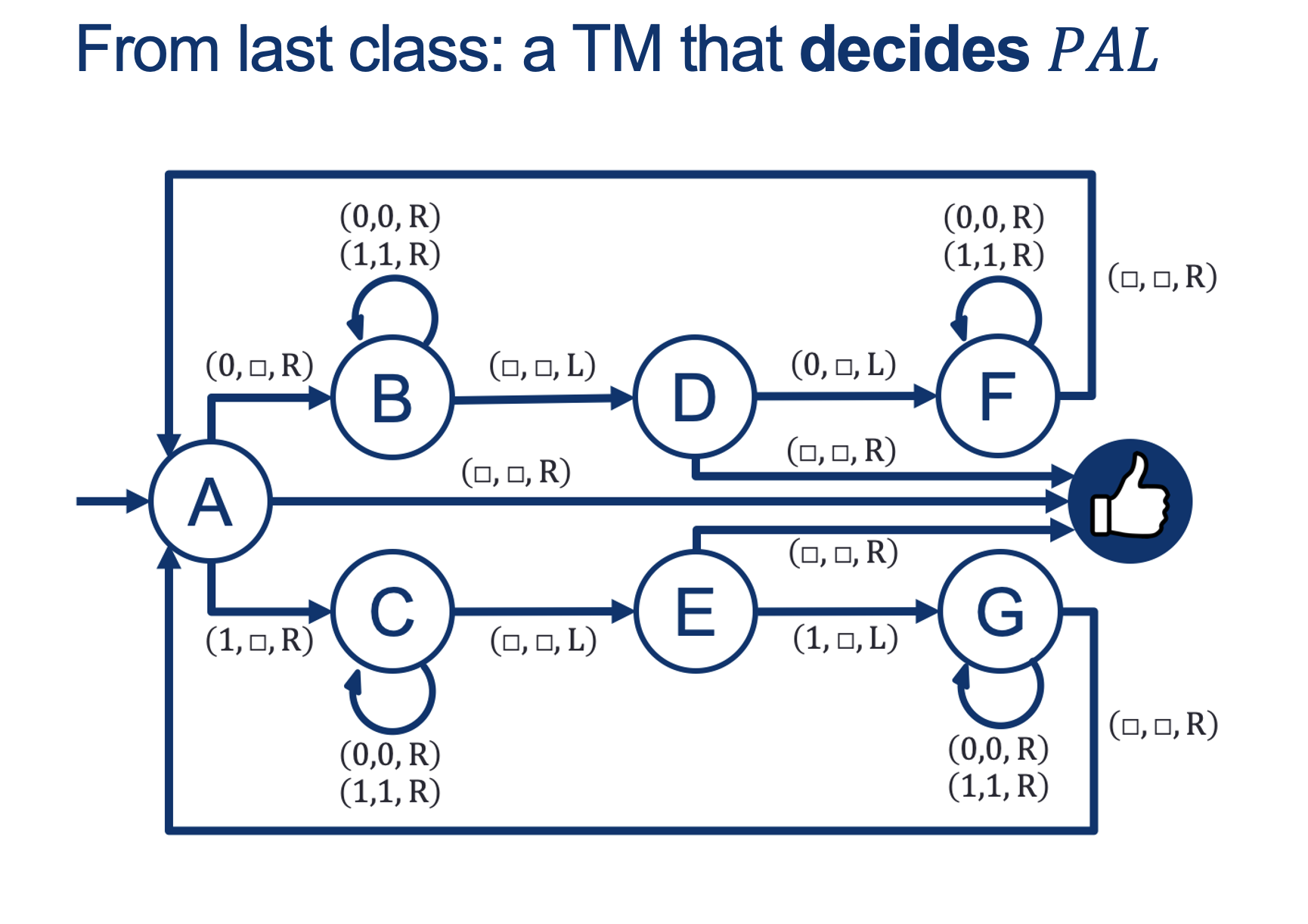

On input w:

while there are symbols left in the tape:

i. note whether 1st letter is a 0 or a 1 and erase it

ii. go all the way to the last symbol

iii. if this symbol doesn't match the one we just erased, REJECT;

otherwise erase it and go back to the start.

ACCEPT.

Big Idea 1: Emulating

If the TM $U$ has arbitrary memory (Tape), we can “save” input descriptions of other machines $M$ and, given a word $w$ as input, process the word using the rules we read from the tape and interpret with the states described in $M$.

In other words, TM $U$ can emulate other turing machines $M$ for some input $w$

Big Idea 2: Input Descriptions

If TM $U$ can emulate $< M, w >$,

We can make the input $w$ the description of another machine $ M_2 $

In other words, TM $U$ can emulate other turing machines $M$ that can get as input, other turing machines $w = description(M_2)$

Or $U$ emulates $< M, description(M_2) >$ or just $< M, M_2 >$

Where we left off…

- Isn’t just looking for a while (true)?

-

How about an example problem:

\[\begin{align*} &n = 19 \\ &while \ (n != 1): \\ & \quad if \ n\%2 == 0: \\ & \quad \quad n = n/2 \\ & \quad else : \\ & \quad \quad n = 3*n + 1 \\ \end{align*}\]

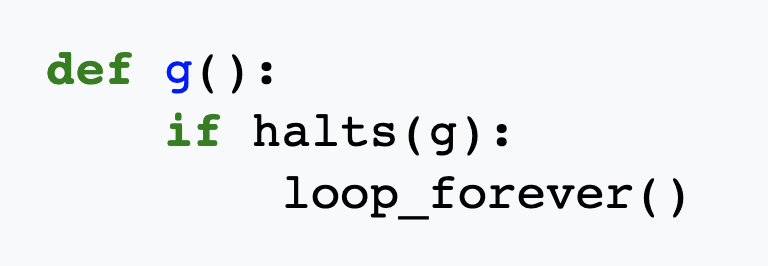

And now a proof that the halting problem is an actual thing:

How about an example problem:

Assume we have a turing machine H that decides (Accept AND Reject) HALT :

\[\begin{align*} &M_{HALT}: \\ & \text{On INPUT $< M, \hat{w} >$} \\ & \quad \text{ if M HALTS on $\hat{w}$, ACCEPT } \\ & \quad \text{ if M FLOOPS on $\hat{w}$, REJECT } \end{align*}\]Note that this is the same as:

\[\begin{align*} &M_{HALT}: \\ & \text{On INPUT $< M, \hat{w} >$} \\ & \quad \text{ if M ACCEPTS $\hat{w}$, ACCEPT } \\ & \quad \text{ if M REJECTS $\hat{w}$, ACCEPT } \\ & \quad \text{ if M FLOOPS on $\hat{w}$, REJECT } \end{align*}\]Since there are no restrictions on what w looks like, it’s possible that w could be the description of another machine.

(this is actually pretty familiar: that’s exactly what a compiler is, right? A program that takes another program as input)

Let’s use this machine to define a new helper machine called $M_X$:

\[\begin{align*} &M_X: \\ & On \; INPUT \; < M > \\ & \quad \text{Make } \hat{w} = < M > \color{gray}{ \text{# a copy of the input machine's description} }\\ & \quad \text{run $M_{HALT} ( < M , \hat{w}>)$} \quad \color{gray}{ \text{# run $M_{HALT} ( < M , < M > > )$ } } \\ & \quad \text{if $M_{HALT}( < M , \hat{w} > )$ returns ACCEPT, FLOOP on purpose } \\ & \quad \text{if $M_{HALT}( < M , \hat{w} > )$ returns REJECT, ACCEPT } \\ \end{align*}\]- This machine just takes in the description of a machine $ < M > $ as input (no w)

- It then creates an input word $\hat{w}$ with its own description

-

Lastly, it calls $M_{HALT}$ to check if the input machine HALTS on its own description and:

- If $M_{HALT}$ predicts that the input machine HALTS on its own description (ACCEPT), $M_X$ FLOOPS on purpose (imagine a $While(True)$ Loop);

- If $M_{HALT}$ predicts that the input machine FLOOPS on its own description (REJECT), $M_X$ ACCEPTS!

So, What happens if we run $ M_{X} ( < M_{X} > ) $?

I’ll replace $< M >$ with $< M_X >$ in the pseudocode shown above (and use that explicitly instead of $\hat{w}$):

\[\begin{align*} &M_X: \\ & On \; INPUT \; < M_x > \\ & \quad \text{run $M_{HALT} ( < M_x , M_x > )$}\\ & \quad \text{if $M_{HALT}( < M_x , M_x > )$ returns ACCEPT, FLOOP on purpose } \\ & \quad \text{if $M_{HALT}( < M_x , M_x > )$ returns REJECT, ACCEPT } \\ \end{align*}\]- This run of $M_X$ takes in the description of itself $< M_X >$ as input

-

It calls $M_{HALT}$ to check if it HALTS on its own description (remember that $M_{HALT}$ should always have a consistent answer!):

- If $M_{HALT}$ predicts that $M_{X}$ HALTS on its own description (ACCEPT), $M_X$ FLOOPS on purpose… But that means that we just FLOOPED when runing $M_{X}$ with its own input (which is exactly the opposite of what $M_{HALT}$ predicted!)

- If $M_{HALT}$ predicts that $M_{X}$ FLOOPS on its own description (REJECT), $M_X$ ACCEPTS!… But that means that we just HALTED when runing $M_{X}$ with its own input (which is exactly the opposite of what $M_{HALT}$ predicted!)

A CONTRADICTION

Since the ONLY assumption was that $M_{HALT}$ exists, then that means that $M_{HALT}$ cannot exist!